The Farce of Banning Films Before Their Release By The Governments

Manwendra Kumar Tiwari

24 Nov 2017 10:24 AM IST

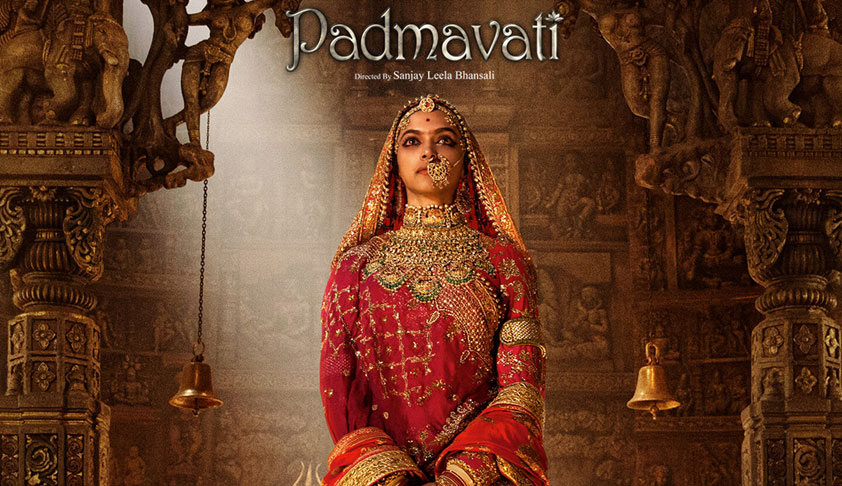

Substantive morality of Constitution in the context of the right to freedom of speech and expression would mean fixing the ambit of this right with precision. The most important goal of constitutional morality, however, to quote, Sujit Chaudhary, Madhav Khosla and Pratap Bhanu Mehta is “to avoid revolution, to turn to constitutional methods for the resolution of claims.”[1] This constitutional morality of ‘form’ or ‘procedure’ is the condition precedent for a debate on substantive constitutional morality pertaining to any issue. It is ironic though that the top political executive of few States have got such contempt for the constitutional morality of form, by becoming the self appointed arbiters of substantive constitutional morality. Padmavati, the movie is yet to be considered by the Board of Film Certification (hereinafter referred to as Board) which is popularly called the Censor Board,[2] a statutory body ordained by the law[3] passed by the Parliament of India to perform the task of sanctioning films for public exhibition and we have the few State Governments having already expressed their desire to not allow the movie to be screened in their respective States. It is to be noted that the Board of Film Certification is not only a film certifying authority for different kinds of audience, rather it has the power to ask to excisions and modifications or it can altogether refuse to sanction a film for public exhibition.

Prior to the Amendment of the Cinematograph Act, 1952 in the year 1981 (w.e.f. 1983) the appeals against the decision of the Board in relation to certification and sanctioning of the films were to lie before the Central Government, and it was only after the intervention by the Supreme Court of India in K. A. Abbas v. Union of India[4] wherein the Central Government gave the assurance before the constitution bench of the Court that the Government will suitably amend the Act to constitute a tribunal to hear the appeals against the decision of the Board instead of Government. The Supreme Court made the following observation:

“We express our satisfaction that the Central Government will cease to perform curial functions through one of its Secretaries in this sensitive field involving the fundamental right of speech and expression. Experts sitting as a tribunal and deciding matters quasi-judicially inspire more confidence than a Secretary and therefore it is better that the appeal should lie to a court or tribunal.”

Keeping in view the fact that the appellate tribunal got constituted pursuant to this intervention by the Court to be headed by either a former judge of the High Court or by a person who is qualified to be appointed as a judge of the High Court, the Supreme Court in Union of India v. K. M. Shankarappa[5] declared section 6(1) whereby the Central Government sought to retain with it the power to pass such orders as it deems fit even after the decision of the Board or the appellate tribunal. The Supreme Court while declaring this part of section 6(1) of the Act unconstitutional stated it to be “a travesty of the rule of law which is one of the basic features of the Constitution.” The Court was of this view that once the quasi-judicial decision is given by the Appellate tribunal it is binding so far as the executive is concerned and a Secretary or a Minister cannot sit in appeal over such decision. Section 6(1) attempts the reverse the constitutional scheme of subjecting administrative decisions to judicial scrutiny by providing for the opposite. The Court made another very important observation:

“We fail to understand the apprehension expressed by the learned counsel that there may be a law and order situation. Once an expert body has considered the impact of the film on the public and has cleared the film, it is no excuse to say that there may be a law and order situation. It is for the State Government concerned to see that law and order is maintained. In any democratic society there are bound to be divergent views. Merely because a small section of the society has a different view, from that as taken by the tribunal, and choose to express their views by unlawful means would be no ground for the executive to review or revise a decision of the tribunal. In such a case, the clear duty of the Government is to ensure that the law and order is maintained by taking appropriate actions against persons who choose to breach the law.”

It is crystal clear therefore that the Governments do not enjoy the power to sanction the public exhibition of films and certainly not the power of excision or modification under the Cinematograph Act. However, the grounds for the imposition of reasonable restrictions by law are certainly not exhausted by the provisions of Cinematograph Act only. But so far as pre-censorship is concerned, it is very onerous to argue that the Governments can still invoke other laws covered under the ambit of Article 19(2) for this purpose. Exercise of such an executive power therefore is constitutionally suspect bordering on unconstitutionality. The only plausible legitimate ground for the exercise of pre-censorship by the Government would be ‘public order’ under Article 19(2) of the Constitution, since all the other grounds under this Article namely, decency, morality, defamation, contempt of court, sovereignty and integrity of India, security of State and friendly relations with foreign State are not fluid concepts as these are not susceptible to the situation on the ground. The meaning of public order is always to be derived from the situation on the ground and not from the possible influence of the film to affect the public order. So, the yardstick for the imposition of public order ground is certainly empirical and not normative.

The Supreme Court, however, in Prakash Jha Productions v. Union of India[6] in relation to the film Aarakshan held that after the film is passed by the Board for public exhibition, a high powered committee appointed by the Government of Uttar Pradesh cannot recommend deletion of certain scenes/words from the film, as this would amount to pre-censorship which is not permissible. Therefore, it seems that beyond the ambit of Cinematograph Act, the Government can only impose a ban on the screening of the movie for its adverse impact on the public order. But even this is a very difficult premise to justify for the Government as the Supreme Court in its order in Prakash Jha Productions stated that once the board has cleared the film for public viewing, screening of the film cannot be prohibited by the State as sought to be done by the State of Uttar Pradesh in this case. In this case the State of Uttar Pradesh had passed an order suspending the screening of the film Aarakshan on the ground that the screening of the film as passed by the Board may lead to breach of peace and breach of law and order in the State. The Court did not accept this argument as the film was being screened already in other States within India which are equally sensitive as the State of Uttar Pradesh.

The court, though, has not completely negated the possibility of invoking the public order ground as per law by the Government to suspend the screening of a film passed by the Board/Tribunal but as it is evident, selective suspension of screening by few States on the ground of public order will have to further justify the fact that the situations in other States where the film is being screened are different compared to the State which has suspended the screening of the film. This certainly is a very onerous requirement to meet. Disturbance of public order itself is an onerous requirement as this is not the same as disturbance of law and order. Supreme Court in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India[7] also clarified this fact that the disturbance of public order must be distinguished from acts against the individuals which do not disturb the society to the extent of causing a general disturbance of public tranquillity. This makes suspension of screening of the film by any Government without having allowed the public exhibition of the film first, almost impossible. When the odds are so heavily stacked against the Government wanting to ban or censor movies before the release of the film for screening, it makes a reasonable person cringe seeing how some of the top political executives slyly conduct themselves by playing to the gallery for narrow political objectives in the recent controversy surrounding Padmavati.

[1] Sujit Chaudhary, Madhav Khosla and Pratap Bhanu Mehta, “Locating Indian Constitutionalism” in Sujit Chaudhary, Madhav Khosla and Pratap Bhanu Mehta (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Indiam Constitution (Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2016) at page 4.

[2] Prior to 1983 it was ‘Board of Film Censors’.

[3] The Cinematograph Act, 1952.

[4] (1970) 2 SCC 780.

[5] (2001) 1 SCC 582.

[6] (2011) 8 SCC 372.

[7] (2015) 5 SCC 1.

Manwendra Kumar Tiwari is an Assistant Professor at Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow.

[The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of LiveLaw and LiveLaw does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same]