Next Story

14 Oct 2016 2:54 PM IST

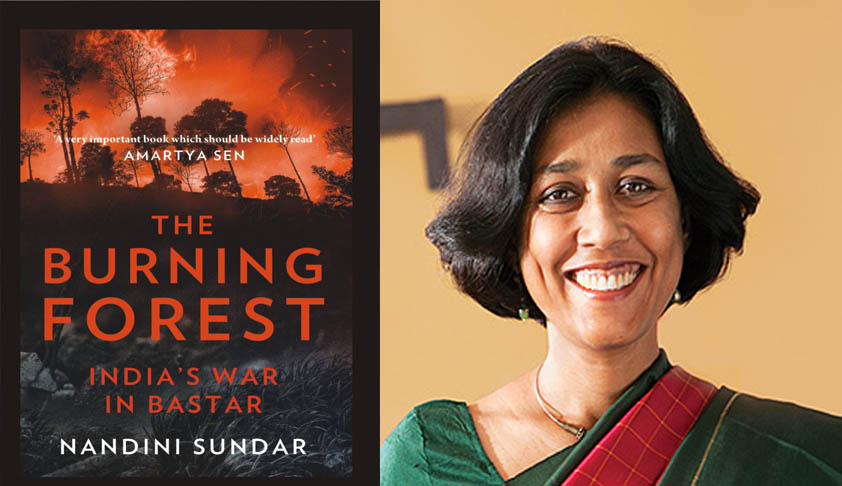

Among the many anecdotes which Nandini Sundar narrates in her latest well-researched book-'The Burning Forest: India’s war in Bastar', the readers will surely find this amusing:Every time the case she filed against Salwa Judum was listed for hearing in the Supreme Court, Nandini Sundar made offerings at the tomb of a medieval ‘judge saab’ in the scrub jungle near her home in Delhi,...