- Home

- /

- Book Reviews

- /

- Probing violence of different...

Probing violence of different dimensions

Review Editor

8 Aug 2016 11:42 AM IST

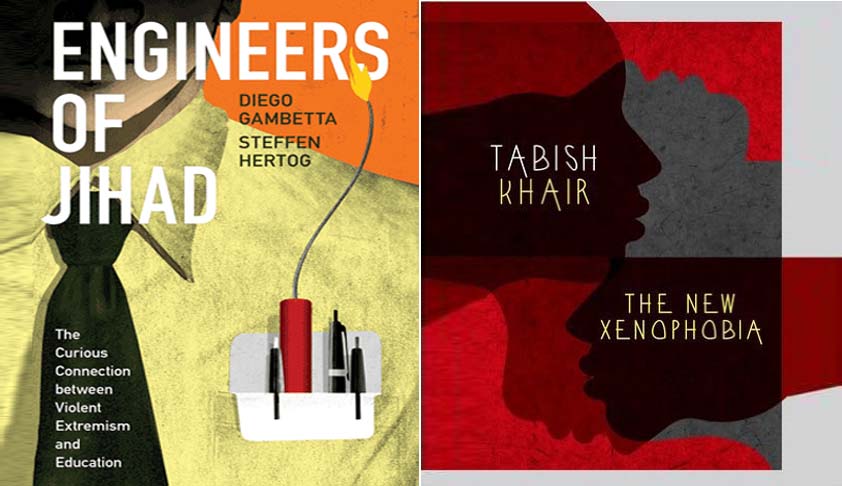

ENGINEERS OF JIHAD: The Curious Connection between Violent Extremism and Education. By Diego Gambetta and Steffen Hertog, Princeton University Press, 2016.THE NEW XENOPHOBIA. By Tabish Khair, OUP, 2016.These two books address different concerns of people living in plural societies.To what extent, our laws aimed at preventing terrorist acts, reflect an understanding of the mind of a...

Next Story