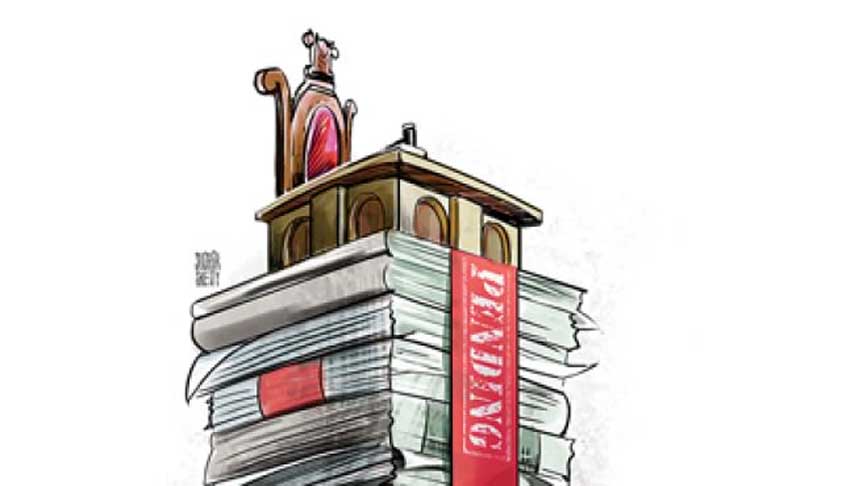

See You In Court” Or “See You Out Of Court”? A burdened Judicial System; Can ADR System Be An Answer? Part II

Richa Kachhwaha

16 May 2017 12:38 PM IST

OVERVIEW

The practice of amicable settlement of disputes is as ancient as the Vedic civilization when disputes between members of a particular occupation or community/area were resolved by elders through a council of village known as panchayats.

The panchayats dealt with a variety of disputes - contractual, matrimonial, even criminal in nature (The Law and Practice of Arbitration and Conciliation, OP Malhotra, second edition, 2006).

The decision of the panchayats was respected and hence a settlement arrived at in pursuance of the mediation by a panchayat was considered binding.

To quote Martin CJ, “Arbitration was indeed a striking feature of ordinary Indian life and it prevailed in all ranks of life to a much greater extent than was the case of England. To refer matters to a panch was one of the natural ways of deciding many disputes in India”(The Arbitration & Conciliation Act with Alternative Dispute Resolution, OP Tewari, 4th Edition (Reprint 2007)).

Judicial administration underwent a drastic change during the British rule. The British ignored the indigenous dispute resolution mechanisms and established a judicial system in India, similar to that of British courts of the time. The introduction of their legal system led to a gradual decline in the traditional methods of settling disputes.

The Civil Procedure Codes (enacted in years 1859, 1877 and 1882) codified the procedure of civil courts and also dealt with arbitration between parties to a suit and arbitration without the intervention of a court.

1940 was a watershed year in the history of arbitration law in British India. The Arbitration Act of 1940 consolidated the laws relating to arbitration and was largely based on the English Arbitration Act, 1934.

The Act of 1940 (in place for nearly half a century) was by and large skeptical of the arbitral process and offered multiple occasions to litigants to approach the court for the latter’s intervention.

Together with a sluggish judicial system, the old law led to delays making arbitrations inefficient.

A telling commentary on the working of the old Act can be found in a Supreme Court ruling of 1981, where Justice Desai lamented, ‘the way in which the proceedings under the (1940) Act are conducted and without an exception challenged in Courts, has made lawyers laugh and legal philosophers weep…”.

Moreover, the phenomenal growth in commerce and industry in the post -liberalisation years meant that the old law was becoming increasingly inadequate to meet the demands of domestic and international commercial disputes.

A “progressive piece of legislation” was brought in the form of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 to modernise the 1940 Act. Based on the UNCITRAL (United Nations Commission on International Trade Law) Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration of 1985 and the ICC (International Chamber of Commerce) Arbitration Rules, the 1996 Act was aimed at making arbitration less technical and more useful and effective by removing several defects of the old arbitration law and incorporating modern concepts of arbitration.

The 1996 law was hailed as a landmark in the struggle to put in place an effective alternative regime to the traditional adversarial system of litigation.

The courts in India also seemed by and large in sync with the spirit of the 1996 law. But prior to 2012, the arbitration experience in the country was far from encouraging.

Indian courts received flak from the business community for their undesirable intervention in foreign-seated arbitrations.

The long-drawn, costly ad-hoc arbitration proceedings were not allowing to develop an arbitration-friendly environment and the 1996 law did little to address these concerns.

Taking note of the criticism to the 1996 arbitration law, the Law Commission submitted a report in August 2014 recommending several changes to the 1996 Act.

In October 2015, Arbitration Ordinance was promulgated with the objective of restraining judicial intervention in arbitration, and tackling inordinate delay with arbitration-related court actions.

Since the amendments were brought through an ordinance (which is temporary in nature), confusion and uncertainty prevailed.

The Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2015, was finally notified and brought into force with retrospective effect from October 23, 2015.

It brought in much needed changes to the 1996 Act by offering clarity with respect to interim relief for foreign seated arbitrations; judicial intervention; independence of the arbitral tribunal; and introduction of measures to make arbitration in India time and cost effective.

Apart from some deviations, the Amendment Act largely conforms with the Law Commission Report and the Arbitration Ordinance.

Compromise and settlement are integral to all ADR methods, which go a long way in preserving and enhancing personal and professional relationships which might otherwise be jeopardised by pursuing litigation.

The success of ADR, quite obviously depends on willingness of the parties to get their disputes resolved by using the services of expert(s).

Secondly, there must be sound substantial law in place for resolving the particular kind of dispute(s).

Availability of trained experts to act as arbitrators is another critical aspect. Last, but certainly not the least, an ADR culture, i.e., courts as well as adjudicators should adopt an arbitration friendly attitude.

It is worth debating if we have indeed succeeded in inculcating a culture of arbitration within the Bar, the Bench, and the arbitration community.

ARBITRATION

To quote former Chief Justice of India Justice Ahmedi: "Of the total number of cases which go to the court, hardly 50 per cent require adjudication by a court on the issues of law. Most of the cases, almost 50 per cent or more, essentially involve issues of fact, and they can certainly be resolved, outside the court."

Over the years, arbitration has emerged as a preferred option to settle commercial disputes globally and to a large extent in India. Commercial contracts, particularly international ones, tend to be detailed and verbose vis-à-vis duties and remedies. Dispute resolution provisions, however, can often be unclear and sometimes unhelpful to a speedy resolution. Non-Indian parties have been traditionally reluctant to accept the Indian courts to have jurisdiction, given the delays in concluding litigation.

Historically, one of the chief concerns of foreign parties to arbitration with their Indian counterparties was the difficulty in enforcing arbitration awards in India. That changed with the Supreme Court pronouncing a string of decisions which have been supportive of international arbitration in India, as well as the latest amendments to the arbitration law.

From restricting the circumstances where a non-Indian arbitration award can be challenged on enforcement in India on the grounds of public policy; to restricting the ability of the courts in India to intervene and grant interim remedies where the seat of arbitration is agreed to be outside India, the arbitration regime in India has undergone a notable change.

With “Ease of doing business” dominating the economic agenda of the current government, facilitating speedy enforcement of contracts, quick recovery of monetary claims and accelerating the process of dispute resolution through arbitration have become sine qua non for projecting India as an investor friendly destination.

The changes made by the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2015 (“Amendment Act”) are aimed at making legal regime more pro-arbitration, in addition to bringing clarity to provisions, which were earlier subject to frequent judicial scrutiny. Strict time limits and reduced judicial intervention deserve particular attention, for they will assist in avoiding delay tactics during arbitration proceedings. But perhaps what is most noteworthy is the clarification with regard to the power of the arbitral tribunal to grant interim relief.

Will these (and other changes) in the arbitration regime transform arbitration into a “one-stop solution” for resolution of commercial disputes? We take a look at some of the noteworthy amendments as well as the problem areas in the amendments:

Key Amendments to 1996 Arbitration Act

- Interim Relief from Court

The Amendment Act discourages the court from accepting an application for interim relief after the constitution of the arbitral tribunal, unless the party seeking such relief can prove that the arbitral tribunal is unable to provide a similar effective remedy. Further, where a party secures an interim relief from the Court prior to the commencement of arbitration proceedings, the arbitration proceedings must commence within 90 days from the grant of such interim measure, or a within a time period specified by the Court, failing which the interim relief will cease to operate. This change is likely to discourage parties from using interim reliefs by way of obtaining ex-parte or ad interim orders as a dilatory tactic and, thereafter, not proceed with arbitration.

Moving on, after judgment of the Supreme Court in Bharat Aluminium and Co vs Kaiser Aluminium and Co [(2012) 9 SCC 552], Indian courts had no jurisdiction to intervene in arbitrations which were seated outside India.

Consequently, interim reliefs given by arbitral tribunals outside India could not be enforced in India, inconveniencing parties who had chosen to arbitrate outside India. This anomaly has now been addressed in section 2(2) of the Amendment Act, which makes the provision for interim relief(s) also applicable in cases where the place of arbitration is outside India (subject to an agreement to the contrary). However, this option is only applicable to parties to an "international commercial arbitration" with a seat outside India; and not to two Indian parties who choose to arbitrate outside India!

- Interim Relief from Arbitral Tribunal

Section 17 (Interim Measures ordered by Tribunal) has been amended in order to empower the arbitral tribunal with the same powers as that of a court under Section 9 (Interim Measures by Court).

The Amendment Act provides that once the arbitral tribunal has been constituted, courts cannot entertain application for interim measures (unless there are circumstances which make the remedy of obtaining interim orders from the arbitral tribunal ineffectual).

The Amendment Act also clarifies that such interim measures granted by the arbitral tribunal would have the same effect as that of a civil court order under the Civil Procedure Code 1908. This is a significant change as the interim orders of the arbitral tribunal under the 1996 law could not be statutorily enforced, rendering them practically redundant. This amendment empowers the arbitral tribunal considerably, given that interim measures granted by a tribunal under the 1996 Act could not be enforced easily. This move will facilitate the parties to approach arbitral tribunal and reduce court intervention.

It is ironical that in a recent judgment passed by the Kerala High Court on March 16, 2016 (Writ Petition (Civil) No. 38725 of 2015), the single judge took a view that under the Amendment Act, the arbitral tribunal cannot pass an order to enforce its own orders and the parties will have to approach the courts for seeking such enforcement.

Only time will tell how other courts of the country will interpret this judgment and if at all it will stand the test of further judicial scrutiny, for such decisions will make the enforcement of arbitral awards cumbersome!

- Judicial Assistance for Foreign-seated Arbitration

In addition to interim relief, Amendment Act also authorises parties in an international commercial arbitration seated outside India to seek judicial assistance in taking evidence under Section 27. The definition of ‘court’ in section (2e) has been, accordingly, revised to ensure that in the case of an international commercial arbitration, the court approached is only a high court. This should expedite the court process since parties no longer have to approach the lower courts, which may be unfamiliar with arbitration, and instead approach only high courts which have more experience in dealing with international disputes.

- Grounds for Challenging Arbitral Award

The Supreme Court, in ONGC Limited vs Western Geco International Limited [(2014) 9 SCC 263], had expanded the scope of "public policy" to include Wednesbury principle of reasonableness entailing a review on merits of an arbitral award. On the recommendation of the Law Commission, section 34 (Application for setting aside arbitral award) has been amended to narrow down the scope of "public policy".

Explanation 1 to the term ‘Public Policy of India’ has now been substituted in section 34(2)(b), under which arbitral award can now be set aside ONLY if it (i) was induced or affected by fraud or corruption; or (ii) is against the fundamental policy of India; or (iii) conflicts with the most basic notions of morality or justice.

The Amendment Act does not allow the setting aside of an award in international commercial arbitration under the garb of public policy, on the grounds of a patent illegality appearing on the face of the award.

The patent illegality ground, outlined by the Indian Supreme Court in Phulchand Export Ltd vs OOO Patriot and ONGC vs Saw Pipes, has been reversed by the amendment to prevent parties as also courts from misusing the ground of public policy to reopen the merits of a foreign arbitral award in an enforcement proceeding.

- Independence/Neutrality of Arbitrator

When a person is approached for possible appointment as arbitrator, he is required to disclose in the writing any relationship or interest which is likely to give rise to justifiable doubts as to his neutrality (section 12). The Amendment Act has brought in further changes to ensure neutrality of arbitrators. A person having relationships (as specified in the new Seventh Schedule) will now be ineligible to be appointed as an arbitrator; for instance, when arbitrator is an employee, consultant, advisor or has any other past/present business relationship with a party to the dispute; or the arbitrator is a manager, director or part of the management, or has a controlling influence over the parties. Further, Fifth Schedule now lists the grounds giving rise to justifiable doubts as to the independence of arbitrators.The aim is to assist parties to ascertain the independence of arbitrators and limit the scope of challenging their appointment.

- Appointment of Arbitrator by Court

Another significant amendment is introduction of sections 11(13) and (14). Section 11(3)provides that an application for appointment of an arbitrator or arbitrators shall be disposed of as expeditiously as possible, and endeavour shall be made to dispose of the matter within 60 days from the date of service of notice on the opposite party. Section 11(13) aims to enable applications for the appointment of arbitrators to be dealt with in a timely manner by providing that the power to appoint arbitrators can be delegated by the Supreme Court or the High Court to any person or entity. Section 11(14) states “for the purpose of determination of fees of the arbitral tribunal and the manner of its payment to the arbitral tribunal, the High Court may frame rules as may be necessary, after taking into consideration the rates specified in the fourth schedule”.

- Fast Track Arbitration

Fast-track or expedited arbitration is recognised by the rules of several arbitral institutions (including International Chamber of Commerce). The Amendment Act introduces a fast-track arbitration procedure (provided such option is exercised prior to or at the time of appointment of arbitral tribunal)to provide relief to parties who face tremendous commercial impact due to time lag and delay in dispute resolution.

To begin with, the Arbitral tribunal shall hold oral hearing for the presentation of evidence or oral arguments on the day-to-day basis and shall not grant any adjournments without any sufficient cause (amended section 24).The right of the respondent to file statement of defence stands forfeited if the respondent fails to communicate such statement in accordance with the time line agreed by the parties or Arbitral Tribunal (under section 23(1) of the Act) without reasonable cause (amended section 25).

Notably, a new provision (section 29A) has been inserted pursuant to which the Arbitral Tribunal shall ensure speedy completion of arbitration proceedings and pass the award within 12 months from the date when the arbitral tribunal enters upon the reference.This period can only be extended for a maximum period of up to six months, with the consent of the parties. If the award is not made within specified period or extended period, the mandate of the arbitrator shall terminate unless the time is extended by the court. Another new provision (section 29B) has been brought in. This section provides for a fast track procedure for conducting arbitral proceedings in cases where the parties mutually agree for such procedure. In such cases, the arbitral tribunal consisting of a sole arbitrator shall decide the dispute on the basis of written pleadings, documents and written submission and shall not hold oral hearing. The award is to be made within six months from the date the arbitral tribunal enters upon the reference.

- Monetary Incentive

Interestingly, the Amendment Act has linked the arbitrator’s fee to the time taken to pass the final award and entitles the arbitrators to additional fees if the award is made within a period of six months. Further, the courts have also been empowered to order a reduction of fees if there is a delay beyond 18 months in passing the final award, for reasons attributable to the arbitrators.

Problem Areas Persist

That the Amendment Act is a significant step forward in overcoming the systemic chain of delays, high costs and ineffective resolution of disputes, plaguing the arbitration regime in India, cannot be denied. But a number of questions have also arisen on the new law. Is the Amendment Act over ambitious, particularly in relation to the stringent time limits it imposes for rendering of awards? To what extent will the New Act successfully reduce court intervention, since the courts have the power to grant extension of time for rendering the award? Is the fast-track arbitration procedure viable? Will arbitrators sacrifice quality for expedition? In what circumstances will the courts refuse to extend the 12-month time limit for arbitration? And finally, does the overburdened judicial system have the necessary resources to meet the goals of the new law? Since these questions mainly concern Indian-seated arbitration; the fear that (in the short-term) foreign investors may prefer to choose an offshore seat for arbitration instead of agreeing to arbitrate in India is not unfounded.

Two amendments, in particular, are being perceived as problem areas:

Time Limit

As mentioned above, the newly inserted section 29A provides that the arbitral tribunal must give the award within 12 months from the date the tribunal entered reference; this time -period can be further extended by 6 months with the mutual consent of all parties. After the expiry of that 18-month time limit, if parties want a further extension they would have to apply to the Indian courts, which may grant an extension (if it finds that there is sufficient cause). Further, if the court grants an extension of the time period and if the court takes the view that the proceedings were delayed by the arbitral tribunal, the court has the power to order the reduction of fees of the arbitrators by up to 5% for each month of such delay.

The first concern highlighted by experts is that matters which come for arbitration are wide-ranging and so setting uniform timelines for all kinds of arbitrations tantamount to ignoring the wide variance in issues that are bound to arise in arbitration. Secondly, requiring court approval for further extension of time will increase court involvement in on-going arbitrations; and given the overburdened calendar of the courts, this amendment may end up prolonging arbitration timelines, not entirely consistent with the goal of promoting efficient disposal of arbitration cases. Lastly, the ill-effects of the court’s power to reduce the arbitrator’s fees (due to delay in the arbitration timelines) cannot be overlooked for it might pressure the arbitrators to rush up the arbitration proceedings to render an award - just to meet the strict timeline!

Appointment of Arbitrators by Court

The newly inserted section 11(4) has been criticised for being ambiguous. There is a possibility of misuse of this provision in ad hoc arbitrations. A party or both parties to an arbitration agreement may on purpose fail to follow the relevant appointment procedure or to agree upon an arbitrator in order to avail benefit of the Fourth Schedule fee structure, which may be lower than the fee quoted by ad hoc arbitrators. This again may have the undesired effect of increasing judicial interference. Secondly, the extent of applicability of Fourth Schedule is said to be unclear: whether it applies to all arbitrations in India, all arbitrations initiated under Section 11, or all arbitrations initiated except fast-track arbitrations by a sole arbitrator under the newly inserted section 29B.

End Note

A legislative change, although much needed, is not the only requirement for bringing efficiency in the way arbitration is conducted in India. We also need a change in the culture of arbitration or the way we arbitrate. To start with, the attitude towards arbitration needs to change. The pool of legal practitioners specialising in arbitration has to grow and for that, arbitration needs to be seen as an important area of practice rather than being seen as a “second fiddle” to Litigation.

The pool of arbitrators too needs to grow and diversify. There is a general preference and an inclination to appoint retired judges as arbitrators instead of domain experts, which is inhibiting the growth of arbitration as a viable and distinct dispute resolution mechanism. A community of arbitrators, distinct from the court practitioners, now needs to emerge and grow, if arbitration is to be developed as the preferred choice for settling commercial disputes - domestic and international.

The amendments will also have to undergo the scrutiny of courts in India which are known for their interventionist attitude. After all, even the slightest ambiguity in arbitration law can lead to further judicial interference. It will be interesting to observe how the courts interpret these amendments.While the Amendment Act is a step in the right direction, how it operates in practice will ultimately decide whether it will succeed in bringing dynamism to India’s arbitration regime.

LOK ADALATS - INDIA’S UNIQUE ADR MODEL

The traditional concept of settlement of disputes through mediation and negotiation, which was pushed into oblivion during the British period, has been institutionalised in present-day Lok Adalats. In its current avatar, Lok Adalat is akin to a swift settlement meeting presided over by a judge and/or a panel of attorneys, with a neutral party as the judge.Literally translated as people’s court, the underlying principles of Lok Adalats are conciliation and compromise between parties with an element of arbitration since decisions arrived at are typically binding. The uniqueness of a Lok Adalat is that the judge(s) proposes solution(s) to a dispute, which is usually accepted by the parties by virtue of the judge's perceived authority.While some experts describe it as a hybrid of conciliation, mediation and arbitration, Lok Adalats have emerged as a distinct category of ADR being well-suited to the Indian environment, culture and ethos.

The genesis of Lok Adalats dates back to the appointment of the Committee for Implementation of Legal Aid Scheme (CILAS) in 1980 under the chairmanship of former Chief Justice of India PN Bhagwati. The Lok Adalats emerged as a result of the concerns expressed by the committee on the mounting arrears of cases in the courts at various levels of the court system, and the need to organise legal aid for the masses. Camps of Lok Adalat were initially set up on an experimental basis in Gujarat in 1982, and gradually extended throughout the country. To tackle the suits/claims crowding the courts, Lok Adalats were given statutory status with the enactment of the Legal Services Authorities Act 1987.

Lok Adalats are ideal for settlement of not just money related claims, but have also proved to be successful in settling disputes concerning insurance, motor accident claims, partition of suits, damages, matrimonial cases, land acquisition disputes etc. In all these disputes, the scope for settlement is tremendous and so the concept behind Lok Adalats is well-suited for their resolution.

Although equipped to deal with wide-ranging matters, the success of Lok Adalats in settlement of third-party motor claims is particularly noteworthy. Given the increasing number of claims and counterclaims in the Motor Accident Claim Tribunal (MACT), claimants as well as the insurers needed a quick disposal oriented system, and Lok Adalats quickly emerged as the favoured forum for such cases.

One of the most attractive features of Lok Adalats is its “zero-cost” - it is free to all who utilise the system; the court fees paid prior are refunded when settlement is reached (Abdul Hasan vs Delhi Vidyut Board AIR 1999 Delhi 88).

Since it is not strictly bound by procedural laws, the informality of proceedings assists parties to understand their dispute more fully. The decision reached in a Lok Adalat is a final and binding ‘award’; no general appeal mechanism exists and the award is legally recognised as a decree given by the court (as per section 21(2) of Legal Services Authorities (Amendment) Act 1994).Not surprisingly, these Adalats continue to remain integral to India’s “access to justice” framework, despite arbitration and mediation being increasingly promoted as central to its functioning.

National Lok Adalats

National Lok Adalats are routinely organised by the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) along with the respective state legal services authorities in various courts across the country. They have proved to be a shot in the arm for quick and amiable settlement of cases which would otherwise be pending in courts. The success of these adalats is also duly credited to co-operation extended by judges and lawyers.

Most recently, over six lakh cases were settled in the National Lok Adalat in April this year under the patronage of Chief Justice of India Justice JS Khehar and the NALSA Executive Chairman.

According to a press release, “the figure of settlement received are 6.60 lakh cases, out of which 3.68 lakh cases have been reduced from the court pendency and about 2.92 lakh matters are of those disputes which have been arrested before they could be filed in the courts.” (See here).

Similarly, nearly 3.5 lakh cases were settled in the National Lok Adalats held at all levels ranging from district to high courts across the country in February this year.

The Lok Adalats dealt with cases ranging from criminal, recovery, cheque bounce, motor accident claims, family and matrimonial disputes, labour disputes, land acquisition, sales tax, income tax etc. "… more than 3.5 lakh cases, including 1.9 lakh pending and 1.6 lakh pre-litigation cases, have been settled.

The total value of the settlement amount reached is Rs. 1,185 crores," NALSA said in a press statement. (See here).

In another National Lok Adalat held late last year in November 2016, around 18.7 lakh cases worth Rs. 640 crore were settled across the country at all levels from the taluk courts to the Supreme Court.

The Lok Adalat dealt with 7.5 lakh pending and 11.1 lakh pre-litigation cases. Twenty- two pending cases in the Supreme Court were also settled for Rs. 60.75 lakh, NALSA said in its release (See here).

Challenges

It cannot be denied that lawyers can be reluctant to refer the matter for settlement in a Lok Adalat. At other times, parties to the dispute may pressurise the lawyers to hold on to the strict process of court. Lok Adalats can be successful only if the disputing parties participate in these Adalats on voluntary basis and restrain themselves from fighting indefinite legal battles in a court of law.

While inaugurating the Second National Lok Adalat in December 2014, held in all courts across the country, the Supreme Court judge Justice AR Dave had rightly noted that although Lok Adalats are the best way to resolve disputes, “people need to have a big heart and keep their ego under control to get the dispute resolved in the Lok Adalat”.

Perhaps an increased involvement of all stakeholders, including lawyers, social activists, even students of law, in spreading awareness about the working and the benefits of these Adalats, is the best way forward.

Another criticism often faced by the Lok Adalats is that since they are headed by a member of the judiciary, these Adalats have acquired role of a “judicial” forum thereby deviating from the objectives for which they have been organised.

The Kerala High Court had pointed out one of the drawbacks of Lok Adalats as “…the major drawback in the existing scheme of organisation of the Lok Adalat (under Chapter VI of the Legal Services Authorities Act) is that the system of Lok Adalat is mainly based on compromise or settlement between the parties. If the parties do not arrive at any compromise or settlement, the case is either returned to the court of law or the parties are advised to seek remedy in a court of law. This causes unnecessary delay in the dispensation of justice. If Lok Adalat is given power to decide the cases on merits in case parties fail to arrive at any compromise or settlement, this problem can be tackled to a great extent.” (See Law of Arbitration and Conciliation & ADR systems, Avatar Singh, tenth edition, 2013).

The above referred deficiency in Lok Adalats was later addressed in Permanent Lok Adalats, set up for public utility services.

Permanent Lok Adalats have different powers as compared to the Lok Adalats set up by the Central, state, district or taluk legal services authorities.

Unlike the (national) Lok Adalats, the Permanent Lok Adalat has the power to decide the dispute even if one of the contesting parties declines to negotiate for settlement, provided the dispute does not relate to any offence.

Organised under Section 22-B of the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 (inserted pursuant to an amendment in 2002 vide a separate Chapter VI-A ‘Pre-litigation Conciliation and Settlement)’, Permanent Lok Adalats are permanent bodies (with a chairman and two members) providing compulsory pre-litigative mechanism for conciliation and settlement of cases relating to public utility services only like transport service; postal or telephone; power and water supply; hospital service; insurance service.

These Adalats first work towards an amicable settlement between the parties, but if that is not acceptable, they work towards a final settlement, which is deemed to be The Adalat will first work towards an amicable settlement between the two parties but if that is not acceptable, it go for a final settlement which will be deemed to be a decree of the civil court. public utility services as: i) transport service, ii) postal or telephone serive, iii) supply of power, light or water by any establishment or system of public conservancy or sanitation, iv) service in a hospital or dispensary and v) insurance service. public utility services as: i) transport service, ii) postal or telephone serive, iii) supply of power, light or water by any establishment or system of public conservancy or sanitation, iv) service in a hospital or dispensary and v) insurance service. public utility services as: i) transport service, ii) postal or telephone serive, iii) supply of power, light or water by any establishment or system of public conservancy or sanitation, iv) service in a hospital or dispensary and v) insurance service.a decree of the civil court. To appeal against the final settlement, the litigants have to approach the High Court. Permanent Lok Adalats were introduced in a bid to decongest the civil courts of petty disputes relating to public utility services. But these forums are not entirely above suspicion of misuse. A division bench of Patna High Court has recently observed that forums of Permanent Lok Adalat are being misused by dishonest litigants’ connivance with certain judicial officers, who have superannuated and are invited to man such forums. In many districts of Bihar, disputes are being entertained by bodies in the name of Permanent Lok Adalat, irrespective of the fact whether such disputes relate to public utility services as defined in Section 22-A (b) of the Act. (See here). The onus is, therefore, on the state Legal Services Authority to take steps to drive away misconceptions from the minds of the litigants as well as the lawyers so that a continuous Lok Adalat is not confused with Permanent Lok Adalat.

Clearly, Lok Adalat is no longer an experimental model for alternate dispute resolution. It is now a successful model which needs to be replicated in areas which have not yet been brought under the domain/jurisdiction of Lok Adalats. Business disputes as well as matters of public importance, wherein government is also involved in some way, are not yet under the ambit of Lok Adalats.

Further, with new branches of law fast emerging, Lok Adalats will have to be reinvented and re-engineered to face the challenges of a changing legal landscape. Nonetheless, their uniqueness and endurance is unabated. Although not a substitute for the judicial system, Lok Adalats have succeeded in complementing the system by reducing the burden on the courts.

Part I can be read here.

Part III of this article will discuss Mediation in India...

Richa has over 10 years of experience in legal writing and editing. She completed her Masters (LLM) in Commercial Laws from the London School of Economics and Political Science and is a qualified Solicitor in England and Wales. Richa started her career with SNG & Partners, an established pan India banking law firm. She went on to pursue her keen interest in legal research and writing as the Senior Legal Editor with LexisNexis India. Her subsequent stint as the Consulting Editor of Lex Witness, India’s first Magazine on Legal and Corporate Affairs, honed her analytical understanding of legal subjects. She was also involved with setting up of Live Law. A ‘hands-on’ mother of two young children, Richa is currently based with her family in Singapore.

Image from here