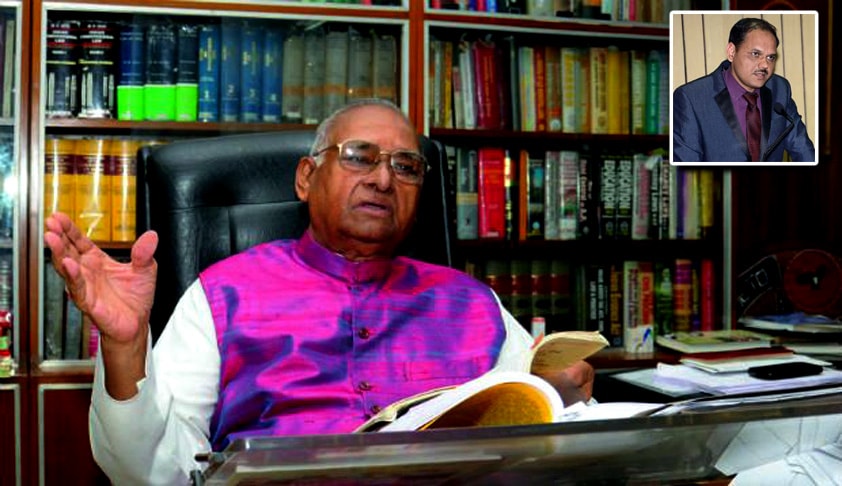

The most serious flaw in NJAC is that any two members of the Commission can veto the decision of the majority which would result in stalling appointments; Interview with Eminent Jurist and Senior Advocate P.P.Rao

Dr.Lokendra Malik

1 July 2015 4:41 PM IST

A doyen of Constitutional Law,Senior Advocate P.P. Rao has been a natural successor to legends such as H.M. Seervai, M.C. Setalvad, C.K. Daphtary, N.C. Chatterjee, S.V. Gupte, A.K. Sen, Niren De, whom he all assisted during his early days.

He was enrolled as an Advocate with Bar Council of Delhi in 1967 and thereafter shifted practice to the Supreme Court. He was designated as a Senior Advocate in 1976. He was elected the President of the Supreme Court Bar Association in 1991, and in 2006, he was awarded the Padma Bhushan.

In his early days he represented the State of Andhra Pradesh as Advocate on Record in ‘Kesavananda Bharati’ and assisted Attorney-General Nirin De in ‘ADM Jabalpur’. Later he had argued a number of leading Cases including A.R. Antulay v R.S. Naik, 1988 Supp (1) SCR 1, S.R. Bommai v Union of India, (1994) 3 SCC 1, P.V. Narasimha Rao v State, (1998) 4 SCC 621, , Ashok Kumar Thakur v Union of India, (2008) 6 SCC 1, M.S. Gill v Chief Election Commissioner, (1978) 1 SCC 403, M. Nagraj v Union of India, (2006) 8 SCC 212 and Ashok Kumar Yadav v. State of Haryana (1985) 4 SCC 417

Be it from defending the President Rule with secularism as its basis, from opposing evil of capitation fees in educational institutions, the octogenarian has appeared in several landmark cases that have shaped the law of the land. A legend in the true sense, Livelaw presents P.P Rao in a freewheeling interview.

LiveLaw : Sir, please tell us something about your entry into legal profession. Why did you leave law teaching for practice? Is law practice better than teaching?

P.P.Rao : As a child, I developed a liking for the legal profession after seeing my uncle and eldest brother, who were lawyers, practising before a District Munsif’s Court at Kanigiri in Andhra Pradesh. They used to work very hard for their clients in distress, earn well, lead a comfortable life, command respect from one and all in the town, render public service and help the needy. By the time I obtained my BA degree, the financial condition of the family had deteriorated due to successive failure of crops and sisters’ marriages for which loans had to be raised. The family was unable to fund my further studies. After serving as a teacher in the District Board High School, Chittoor for one academic year, I joined the LLB course in the Law College of Osmania University at Hyderabad which was then an evening college. During day time I used to work for my living and in the evening attend my classes and study law books late night. After successful completion of LL.B. and LLM courses, as the family was still not in a position to support me, I could not join the Bar. Instead, I joined the teaching line. I was lucky to get an opening in the prestigious University of Delhi as a Research Assistant initially and subsequently, as a Lecturer in the Faculty of Law. I liked the teaching and legal research. Inspired by my colleagues, I started contributing case comments and articles to law journals and newspapers. The area of my specialisation was constitutional law. While working in the Law Faculty, I came in contact with Mr. N.C. Chatterjee, a leading Senior Advocate of the Supreme Court and a Member of Parliament, in 1963 when he sought my assistance for his academic work. On his initiative, in 1966, we jointly wrote the book “Emergency and Law”, published by Asia Publishing House, New York. The reviews were rewarding. After some time, he advised me to join the Bar saying, “You have taught enough. Now you join my Chamber and practise law.” I followed his advice. That was the turning point in my life and career. It was unexpected fulfilment of a long cherished desire.

Both teaching and advocacy are noble professions, being service oriented. A person who follows the traditions and ethics of either profession, will have ample job satisfaction. Success would follow.

LiveLaw : Sir, what is your observation about the working of the Supreme Court during the time when you entered into that court? What was the level of lawyers at that time?

LiveLaw : Sir, what is your observation about the working of the Supreme Court during the time when you entered into that court? What was the level of lawyers at that time?

P.P.Rao : When I joined the profession in July 1967, the Supreme Court was functioning with four Benches. The Judges and leaders of the Bar maintained very high standards. The Judges were mostly well grounded in law who had distinguished themselves while practising at the Bar and subsequently after their elevation. The standards of selection for elevation were more rigorous in those days. The Bar was led by M.C. Setalvad, who was the symbol of dignity, propriety and probity. The standards set by him were followed by the entire Bar. All senior advocates used to charge a fixed and modest fee for appearance at admission, for a conference and for appearance at the final hearing of a case irrespective of the stakes involved. Most of them observed the professional etiquette expected. The Bar enjoyed a great reputation.

LiveLaw : Sir, did you participate in the famous Kesavananda Bharati case? What was the actual bone of contention in that matter? Why the Chief Justice tried to review that judgment during emergency?

P.P.Rao : In Kesavananda Bharati’s case, I have represented the State of Andhra Pradesh as Advocate on Record. I was led by P. Ramachandrareddy, Advocate General for the State. To me, it was a great education to listen to the erudite arguments of seasoned counsel like N.A. Palkhivala, H.M. Seervai, Niren De and others. The bone of contention was whether the Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution was unfettered or subject to limitations. This question was raised earlier in Shakani Prasad Singhdeo v Union of India, 1952 SCR 89 = AIR 1951 SC 458, in Sajjan Singh v State of Rajasthan, (1965) 1 SCR 933 = AIR 1965 SC 845 and in I.C. Golak Nath v State of Punjab, (1967) 2 SCR 762 = AIR 1967 SC 1643, but it was finally settled in Kesavananda Bharti by the largest ever Bench of thirteen Judges by a slender of majority 7:6 declaring that Article 368 does not enable the Parliament to alter the basic structure or framework of the Constitution. It was a historic pronouncement, unprecedented in the constitutional history of any country. There was mixed reaction. Several eminent jurists criticised the judgment. The Central Government could not reconcile to it. On its behalf, a request was made to the Chief Justice of India for a review of the judgment. The Chief Justice assembled a Bench of nine Judges to consider whether the ruling in Kesavananda Bharti required reconsideration. After hearing the powerful arguments of Palkhivala resisting reopening of the case, the Bench was dissolved. Both Justice H.R. Khanna in his book “Neither Roses Nor Thorns” and T.R. Andhyarujina in his book “The Kesavananda Bharati case: The untold story of struggle for supremacy by Supreme Court and Parliament” have written about the abortive attempt to reopen Kesavananda Bharati.

LiveLaw : Sir, what is the overall impact of Kesavananda Bharati judgment on the Indian constitutional law? Has it protected the rule of law and democratic system in our country or is it still an unwelcome judicial product?

P.P.Rao : Notwithstanding the widespread criticism of the law declared in Kesavananda Bharati’s case, the wisdom of the ruling came to be appreciated when Indira Gandhi’s Election Appeal was decided declaring that the obnoxious 39th amendment to the Constitution was violative of the basic structure of the Constitution by an unanimous Constitution Bench consisting of a majority of Judges who had dissented in Kesavananda Bharti. Thereafter, most of the critics of Kesavananda Bharati turned admirers of the law declared therein. The rule of law and parliamentary democracy has been declared to be part of the basic structure of the Constitution by the Supreme Court. The wholesome ruling has its side effects. As the Supreme Court merely illustrated what the basic structure of the Constitution comprises of without exhaustively enumerating all the components of the basic structure, there is uncertainty as to the precise extent of power of Parliament to amend the Constitution. As a result, the Judiciary has emerged as the most powerful wing of the State in comparison to the Legislature and the Executive and it has been expanding the scope of judicial review from case to case. I have dealt with Basic Features of the Constitution, in detail, in my Dr. Alladi Krishnaswamy Iyer Memorial Lecture delivered in 1999, an abridged version of which was published in (2000) 2 SCC Jour 1.

LiveLaw : Sir, how do you see the first judicial supersession in 1973? Could it not have been avoided and what has been its impact on independence of the judiciary?

P.P.Rao : The supersession of the Judges in 1973 was a thoughtless knee-jerk reaction of a powerful Central Government which could not reconcile to the judgment in Kesavananda Bharti. Supersession was ill advised. It has, to some extent, destabilised the judiciary and adversely affected independence of the judiciary. The search for committed judges started simultaneously. The Executive became increasingly over active in the matter of appointments and transfers of Judges of the Supreme Court and the High Courts thereafter.

LiveLaw : Sir, what is your view about the appointment of Chief Justice A. N. Ray? Was Ray a committed judge?

P.P.Rao : Chief Justice A.N. Ray was upset and baffled when he was sounded about his appointment as Chief Justice of India superseding three of his senior judges. He was faced with a Hobson’s choice. If he declined the offer, his immediate junior would be elevated as Chief Justice of India and he would have to serve under him or else, to avoid such embarrassment, he would have to resign his judgeship. Most reluctantly he accepted the offer. It was a painful decision. A.N. Ray was an honest Judge. In every case and on every question of law, very often, two views are possible and the Judge has to choose one of them. He happened to take a possible view in all the cases which came before him, including the Bank Nationalisation case, Privy Purse case and Kesavananda Bharati’s case. I do not consider him to be a committed Judge.

LiveLaw : Sir, what is your view about the 1975 Emergency? Why was it declared and how was it related to the Indira Nehru Gandhi judgment delivered by Justice V. R. Krishna Iyer?

P.P.Rao : The Emergency was an aberration of Indian democracy. It was wholly avoidable. If only Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer who was only a vacation Judge had continued the unconditional stay granted by Justice Jagmohan Lal Sinha of the Allahabad High Court after declaring Mrs. Gandhi’s election void and directed posting of the stay petition before a regular Bench, there would have been no occasion for Emergency at all. The long conditional order of stay granted by him sparked of nation-wide agitation by the leaders of the opposition demanding the resignation of the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister was misled by her short-sighted advisers into getting the proclamation of Emergency issued by President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed.

LiveLaw : Sir, how do you assess the ADM Jabalpur judgment particularly the role of Justice H. R. Khanna in that case?

P.P.Rao : I welcome the judgment of Justice H.R. Khanna in ADM Jabalpur as I do the dissenting judgment of Lord Atkin in Liversidge v Anderson, notwithstanding the fact that I assisted Attorney-General Nirin De in the case for the Union Government. Justice H.R. Khanna’s portrait in Court No.2 is eloquent testimony of acceptance of his judgment by an overwhelming majority of the Bar.

LiveLaw : Sir, the issue pertaining to judges’ appointment has been a critical one in our country ever since the first judges case. What is your observation about the judges appointment in the country and how do you assess the mechanism of collegium system? Are you in favour of NJAC or against it?

P.P.Rao : In the beginning, there was no problem. Prime Ministers Jawaharlal Nehru and Lal Bahadur Shastri showed great respect to the judiciary and accepted almost all the recommendations made by successive Chief Justices of India for appointment of Judges of High Courts and the Supreme Court. After the supersession of Judges in 1973, the attitude of the Central Government changed. I was one of the lawyers who argued for the Collegium system before the nine-Judge Bench in 1993 with the fervent hope that if the judiciary had the last word in the matter of appointments and transfers of Judges; it would strengthen the independence of judiciary. We all hoped that the best of candidates would be selected by the Collegium and vacancies would not remain unfilled for long periods. Experience has belied our expectations. Justice J.S. Varma, the author of the majority judgment in Supreme Court Bar Association v Union of India, (1993) 4 SCC 441, himself was disillusioned about the functioning of the Collegium system. Then we started demanding entrusting the task to a Judicial Commission. The National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution constituted by the NDA Government led by Shri Atal Behari Vajpayee recommended a National Judicial Appointments Commission with five members. Parliament has now made it a six member Commission consisting of the Chief Justice of India, two senior most Judges, the Law Minister and three eminent persons, one of whom shall be a member of a Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe, Backward Class, minority or a woman. The words “eminent persons” are vague and do not reflect the ability to select suitable candidates for higher judiciary. Another and more serious flaw in NJAC is that any two members of the Commission can veto the decision of the majority of members which would result in stalling appointments on the one hand and opening the door for bargaining by the Executive with the Judiciary on the other which would not at all be conducive to the maintenance of independence of judiciary which needs to be strengthened and not diluted any further.

LiveLaw : Sir, it is a matter of fact that Article 356 has been highly misused in our country. It is only the S R Bommai case which put certain breaks on its misuse by the Central Government. How do you see the Bommai judgment and how the President of India can encourage the Union Cabinet to handle such situations? President K. R. Narayanan exercised his referral powers two times. Do you think President A. P. J. Abdul Kalam might have also exercised this option in case of Bihar Assembly dissolution case in 2005?

P.P.Rao : There is no doubt that Article 356 has been largely misused. Justice Sarkaria Commission has noticed this fact. The law declared in S.R. Bommai was an operational necessity. It is settled law that the President of India is not a rubber stamp. When the Union Cabinet advises him to impose President’s rule in a State, he has to apply his mind like a statesman and use his exalted position and good offices to persuade the Government to act wisely and objectively. Like the British Monarch, he has the right to be consulted, the right to encourage and the right to warn, in the words of Walter Bagehot. I do not find fault with the decision to dissolve the Bihar Assembly taken at a time when no party was in a position to form a stable Government and the single largest party in the State Assembly had declined to form a Government. The decision was taken only after horse trading of MLAs has started. I am unable to appreciate the majority judgment of the Supreme Court in Rameshwar Prasad v. Union of India (2006 2 SCC 1 finding fault with the dissolution of the Assembly. On the other hand, the dissenting judgments of Justices K.G. Balakrishnan and Arijit Pasayat appeal to me. In my opinion, President Kalam did not commit any indiscretion or impropriety as the Constitution does not contemplate Governments formed by horse-trading of unscrupulous members of a Legislature.

LiveLaw : Sir, what is your view about the standard of adjudication of matters in the Supreme Court? Do you think the Supreme Court should decide all types of cases or should it confine itself to constitutional questions only? Is there any need to establish National Courts of Appeal in all four major metropolitan cities of India?

P.P.Rao : Over the years, in the absence of good governance free from corruption, nepotism, favouritism, responsive to the people, the volume of litigation has increased to unmanageable proportions and arrears of cases have been mounting up resulting in deterioration in the quality of justice administered. Establishment of Regional Courts of Appeal would go a long way in easing the present congestion. Appointment of Judges of impeccable integrity and ability is also essential. Thereafter the Supreme Court may confine itself largely to constitutional questions and other questions of law of national importance. To liquidate the accumulated arrears of cases, I suggest introducing the shift system in all the Courts utilising the services of recently retired Judges and judicial officers who enjoy high reputation for their ability and integrity.

LiveLaw : Sir, kindly tell us something about your prominent appearances in the Supreme Court particularly the landmark cases which guided the constitutional destiny of the country?

P.P.Rao : I had the privilege of assisting the Supreme Court in laying down the law in several cases in constitutional law, election law and administrative law including service law. A.R. Antulay v R.S. Naik, 1988 Supp (1) SCR 1, S.R. Bommai v Union of India, (1994) 3 SCC 1, P.V. Narasimha Rao v State, (1998) 4 SCC 621, , Ashok Kumar Thakur v Union of India, (2008) 6 SCC 1, M.S. Gill v Chief Election Commissioner, (1978) 1 SCC 403, M. Nagraj v Union of India, (2006) 8 SCC 212 and Ashok Kumar Yadav v. State of Haryana (1985) 4 SCC 417 are some of the important cases wherein I appeared.

The first three cases were the most difficult ones which gave me tremendous job satisfaction.

LiveLaw : Sir, how do you see the judgments of the Supreme Court and High Courts? Are they qualitative or just quantative? How our judges can take inspiration from the judgments of US Supreme Court, U. K. Supreme Court and other prominent constitutional courts in the world?

P.P.Rao : India has produced outstanding judges whose judgments have been acclaimed all over the world. It is difficult to generalise judgments of the Supreme Court and High Courts. Good Judges ably assisted by competent lawyers write sound judgments. There are good Judges in the High Courts and in the Supreme Court even now who can compare with the best in the world. Judges all over the world take inspiration from one another. Judgements of Indian Supreme Court are cited by Judges of other countries. The quality of a judgment reflects the quality of the Judge.

LiveLaw : Sir, is the Supreme Court of India delivering decisions or justice? What is your view about the affordable access to justice? Senior lawyers charge heavy fees and the average people are not able to engage them. So is the legal profession basically a service of mankind or only a moneymaking business? Please throw some light on these issues.

P.P.Rao : The endeavour of every Judge is to do justice barring stray exceptions. Access to justice is not denied to anyone. Legal aid takes care of indigenous litigants. The Middle Income Scheme administered by the Supreme Court Legal Aid Committee takes care of the Middle Income Group of litigants. There are competent lawyers available in the Bar to suit everyone’s pocket. Some of the young lawyers are very good. In the nature of things, it is not possible for prominent senior lawyers to take up every case. One way of limiting their work within manageable level is to charge a high fee. Leading lawyers do not charge fees from poor litigants. They also render legal aid. Legal profession is service oriented and it has to remain as such. Every lawyer should have a fixed schedule of fees irrespective of the stakes involved in a case, which may be revised from time to time. A liberal profession should never become a money making business. Those who indulge in money making violate the professional ethics.

LiveLaw : Sir, how do you see the state of legal education in the country? What is the impact of National Law Schools on legal education? Which law school is best? Who are the brilliant professors whose contribution has enriched the legal education in our country? Do you think that law professors should also become judges of Supreme Court and High Courts in the category of distinguished jurists? Is there any distinguished jurist in Indian legal academia?

P.P.Rao : The state of legal education is deplorable. Bar Council of India has not been able to maintain much less promote high standards of legal education. The Advocates Act requires a thorough revision. National Law Schools, by and large, have been imparting education of better quality but I have reports that in quite a few of them, discipline is lacking and the students are not immune from the menace of drugs etc. The National Law School of India University, Bangalore is generally rated as the best. NALSAR Hyderabad and NLU Delhi are catching up. India has produced several brilliant professors and scholars. Professors G.C.V. Subba Rao, T.S. Rama Rao, P.K. Tripathi, M.P. Jain, Lotika Sarkar, Upendra Baxi and N.R. Madhava Menon, among others, belong to this class. The Constitution contains a provision for appointment of Jurists as Judges of Supreme Court, but no appointment has been made so far from this category. There should be a similar provision for appointment of Jurists as Judges of High Courts as well. There are distinguished Jurists. A few of them have held or are holding the office of Vice Chancellor in National Law Universities.

LiveLaw : Sir, what is the contribution of Justice V. R. Krishna Iyer for the judicial system of the country? Was he not more eminent than any Chief Justice? How his judgments affected the judicial adjudication in the country?

P.P.Rao : Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer was a rare Judge. He has been hailed by F.S. Nariman, the doyen of the Indian Bar, as one of the two pathfinders in the Supreme Court, the other being Chief Justice K. Subba Rao. Justice Iyer was one of the outstanding Judges of the Supreme Court by any reckoning. He raised the stature of the Supreme Court in the eyes of the world and opened the doors of the Supreme Court to Public Interest Litigation. His contribution to the evolution of law, particularly human rights has been immense. He was a source of inspiration to many Judges and Jurists in the country and outside the country.

LiveLaw : Sir, what is your advice for the young lawyers? What is the key of success in legal profession?

P.P.Rao : My advice to young lawyers is to work hard, be straight and honest, conduct yourself with respect to the Court and consideration for the client. Equip yourself with the latest developments in law and current affairs. Don’t become impatient or angry in the discharge of your professional duties. Follow the traditions of the Bar, read the biographies and including autobiographies of great Judges and eminent lawyers. Never stoop law. Maintain self-respect and dignity of the profession.

LiveLaw : Sir, besides being a busy lawyer you also spare time for writings and have written a number of books and articles. How do you manage works, litigation as well as writings? Recently you published a book titled Reclaiming the Vision from the LexisNexis Company, what is the message which you gave through that book to the readers? Are you also writing your memoirs?

P.P.Rao : I generally try to comply with requests for an article or an interview sparing the time required cutting into my leisure. I consider it uncivilised to turn down a genuine request without justification. My book is a collection of my writings from time to time. I am glad that it has been received well by the readers. The message if at all is ‘express your thoughts freely on issues of general interest.’ Several friends and well wishers have been repeatedly asking me to write my memoirs. I have started jotting down a few but I do not know when I will be able to compete the work.

LiveLaw : Sir, please tell us something about the present state of governance in the country? Do you think the country is passing through a difficult time particularly in terms of secular order and inclusive governance?

P.P.Rao : The state of governance is not at all satisfactory. The country is passing through a difficult period. Aims and objects of the Constitution are yet to be realised. Promotion of fraternity assuring the dignity of the individual and the unity and integrity of the nation has not been receiving due attention. Caste based reservation policy and communal vote bank politics keep the people divided. The country has failed to bridge the gap between the rich and the poor to any appreciable extent. Unless Parliament undertakes electoral reforms, administrative reforms and judicial reforms and in particular by laying down by law strict conditions of eligibility for contesting at an election or for holding a high office, good governance will remain a distant goal.

LiveLaw : Sir, what is the role of the Chief Justice of India in the judicial system of the country? Kindly tell us some names of some bright former Chief Justices who have been path-finders?

P.P.Rao : As head of the judicial fraternity, the Chief Justice of India can, by becoming a role model, improve the judicial system. Among the Chief Justices before whom I had the privilege to appear, I consider Chief Justices M. Hidayatullah, S.M. Sikri, Sabyasachi Mukherjee and M.N. Venkatachaliah as outstanding Chief Justices whose portraits deserve to be unveiled in the Supreme Court.

Dr. Lokendra Malik is practicing as an Advocate in the Supreme Court of India with former Union Law Minister Salman Khurshid. He did his Ph.D. in Indian Constitutional Law from Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra and also earned the LL.D. (Post-doctoral) degree from the National Law School of India University, Bangalore in the area of Indian Constitutional Law on Constitutional Position of the President of India under the worthy supervision of Vice-Chancellor Professor R. Venkata Rao. Before joining law practice, Dr. Malik has also been a professor of law at the Indian Institute of Public Administration, New Delhi and taught senior civil servants. Public law is his main area of interest in terms of litigation, academic writings and research. He has been a member of Internship Committee of the Lok Sabha and is also a member of some other prominent academic bodies such as Indian Law Institute and Indian Institute of Public Administration.