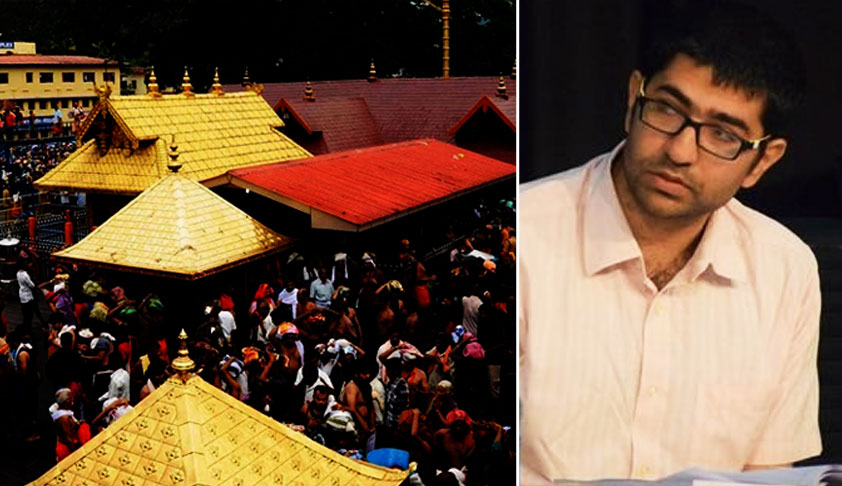

The Sabarimala Judgment – I: An Overview

Gautam Bhatia

3 Oct 2018 8:05 PM IST

Earlier today, a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court held, by a 4 – 1 Majority, that the Sabarimala Temple’s practice of barring entry to women between the ages of ten and fifty was unconstitutional. While the case raised a host of complex issues, involving the interaction of primary legislation (statute), subordinate legislation (rules), and the Constitution, the core reasoning of the Majority was straightforward enough. On this blog, we will examine the Sabarimala Judgment in three parts. Part One will provide a brief overview of the judgment(s). Part II will examine some of the issues raised in the concurring judgment of Chandrachud J. And Part III will analyse the dissenting opinion of Indu Malhotra J.

Let us briefly recapitulate the core issue. The exclusion of (a class of) women from the Sabarimala Temple was justified on the basis of ancient custom, which was sanctioned by Rule 3(b), framed by the Government under the authority of the 1965 Kerala Hindu Places of Worship (Authorisation of Entry Act). Section 3 of the Act required that places of public worship be open to all sections and classes of Hindus, subject to special rules for religious denominations. Rule 3(b), however, provided for the exclusion of “women at such time during which they are not by custom and usage allowed to enter a place of public worship.” These pieces of legislation, in turn, were juxtaposed against constitutional provisions such as Article 25(1) (freedom of worship), Article 26 (freedom of religious denominations to regulate their own practices), and Articles 14 and 15(1) (equality and non-discrimination).

In an earlier post, I set out the following map as an aid to understanding the issues:

(1) Is Rule 3(b) of the 1965 Rules ultra vires the 1965 Act?

(2) If the answer to (1) is “no”, then is the Act – to the extent that it authorises the exclusion of women from temples – constitutionally valid?

(3) If the answer to (2) is “no”, and the Act is invalid, can a right to exclude be claimed under Article 25(1) of the Constitution?

(4) If the answer to (3) is “yes”, then is the exclusion of menstruating women from Sabarimala an “essential religious practice” protected by Article 25(1)?

(5) If the answer to (4) is “yes”, then is the exclusion of women nonetheless barred by reasons of “public order”, “health”, “morality”, or because of “other clauses of Part III”, which take precedence over Article 25(1)?

(6) Do Sabarimala worshippers constitute a separate religious denomination under Article 26?

(7) If the answer to (6) is yes, then is temple entry a pure question of religion?

While the judgments are structured slightly differently, this remains a useful guide. Here is a modified map, with the answers:

(1) Does the phrase “all classes” under the Act include “gender”? By Majority: Yes.

(2) Do Sabarimala worshippers constitute a separate religious denomination under Article 26, and are therefore exempted under the Act from the operation of Section 3? By Majority: No. Malhotra J. dissents.

2(a) Is Rule 3(b) of the 1965 Rules therefore ultra vires the 1965 Act? By Majority, logically following from (1) and (2): Yes. However, Nariman J., instead of holding it ultra vires, straightaway holds it unconstitutional under Articles 14 and 15(1). Malhotra J. – also logically following from 2 – dissents.

(2b) If the answer to (1) is “no”, then is the Act – to the extent that it authorises the exclusion of women from temples – constitutionally valid? Does not arise.

(3) If the answer to (2) is “no”, and the Act is invalid, can a right to exclude be claimed under Article 25(1) of the Constitution? Per Misra CJI and Khanwilkar J.: Yes, in theory. Per Chandrachud J.: No, because it violates constitutional morality. Per Nariman J.: No, because it violates Article 25(1), which stipulates that all persons are “equally entitled to practice religion.” Malhotra J.: Yes.

(4) If the answer to (3) is “yes”, then is the exclusion of menstruating women from Sabarimala an “essential religious practice” protected by Article 25(1)? Per Misra CJI and Khanwilkar J.: No, on facts. Per Nariman J.: Assuming the answer is yes, (3) answers the point. Per Chandrachud J.: No, on facts. Per Malhotra J.: Yes, on facts.

An overview of the judgments handed down by the CJI and Khanwilkar J., and Nariman J., is provided below:

Misra CJI and Khanwilkar J.

Misra CJI and Khanwilkar J. hold that the devotees of Lord Ayappa at Sabarimala have failed to establish that they constitute a “separate religious denomination” (paragraph 88 onwards). This is because the test for “separate denomination” is a stringent one, and requires a system of distinctive beliefs, a separate name, and a common organisation. The Sabarimala Temple’s public character (where all Hindus, and even people from other faiths) can go and worship, along with other temples to Lord Ayappa where the prohibition of women does not apply, leads the two judges to hold that it does not constitute a separate “denomination.” Misra CJI and Khanwilkar J. then hold that the fundamental rights chapter applies to the Temple, as it is governed by a statutory body (the Devaswom Board). Consequently, women have an enforceable Article 25(1) right to entry. This right is not undermined by a contrary right of exclusion because, on facts, excluding women does not constitute an “essential religious practice” that is protected by Article 25(1). This is because no scriptural or textual evidence has been shown to back up this practice (paragraph 122), and it is not possible to say that the very character of Hinduism would be changed if women were to be allowed entry into Sabarimala (paragraph 123). Moreover, on facts, this practice appears to have commenced only in 1950, and therefore lacks the ageless and consistent character that is required of an “essential religious practice” (para 125). Therefore – Misra CJI and Khanwilkar J. hold – since Section 3 of the 1965 Act prohibits discrimination against “any class” of Hindus, and the Temple is not a denominational temple, Rule 3(b) is ultra vires the parent Act, and therefore must fall (paras 132 and 141 – 142).

Nariman J.

Nariman J. accepts, for the purposes of argument, that barring women of a certain age from accessing Sabarimala is an essential religious practice, and therefore protected by Article 25(1) (paragraph 25). However, he agrees with Misra CJI and Khanwilkar J that Sabarimala fails the rigorous test for a “separate denomination.” Article 26, therefore, is not attracted, and the proviso to S. 3 of the Act is not attracted (paragraphs 26 – 27). Therefore, even if there is an essential religious practice excluding women, this practice is hit by Section 3 of the Act, which provides for non-discriminatory access to all “classes” of Hindus (paragraph 28). This is further buttressed by the fact that the 1965 Act is a social reform legislation, and therefore, under Article 25(2)(b) of the Constitution, can override the right to religious freedom (paragraph 28).

However, Nariman J. adds that even otherwise, this case involves a clash of rights under Article 25(1): the right of women to worship, and the right of the priests to exclude them. The text of Article 25(1) – which uses the phrase all persons are “equally entitled” to practice religion, decides the clash in favour of the women. (paragraph 29).

Even otherwise, the fundamental right of women between the ages of 10 and 50 to enter the Sabarimala temple is undoubtedly recognized by Article 25(1). The fundamental right claimed by the Thanthris and worshippers of the institution, based on custom and usage under the selfsame Article 25(1), must necessarily yield to the fundamental right of such women, as they are equally entitled to the right to practice religion, which would be meaningless unless they were allowed to enter the temple at Sabarimala to worship the idol of Lord Ayyappa. The argument that all women are not prohibited from entering the temple can be of no avail, as women between the age group of 10 to 50 are excluded completely. Also, the argument that such women can worship at the other Ayyappa temples is no answer to the denial of their fundamental right to practice religion as they see it, which includes their right to worship at any temple of their choice. On this ground also, the right to practice religion, as claimed by the Thanthris and worshippers, must be balanced with and must yield to the fundamental right of women between the ages of 10 and 50, who are completely barred from entering the temple at Sabarimala, based on the biological ground of menstruation.

And insofar as Rule 3(b) is concerned, Nariman J. holds it directly contrary to Article 15(1), and strikes it down.

Consequently, like the Majority – but using a different approach – Nariman J. holds in favour of the right of women to enter Sabarimala.

This article was first published Here