Supreme Court Dismisses PIL Seeking 2 Years' Cooling Off Period For Retired Judges' Post-Retirement Appointments

Awstika Das

6 Sept 2023 2:00 PM IST

Next Story

6 Sept 2023 2:00 PM IST

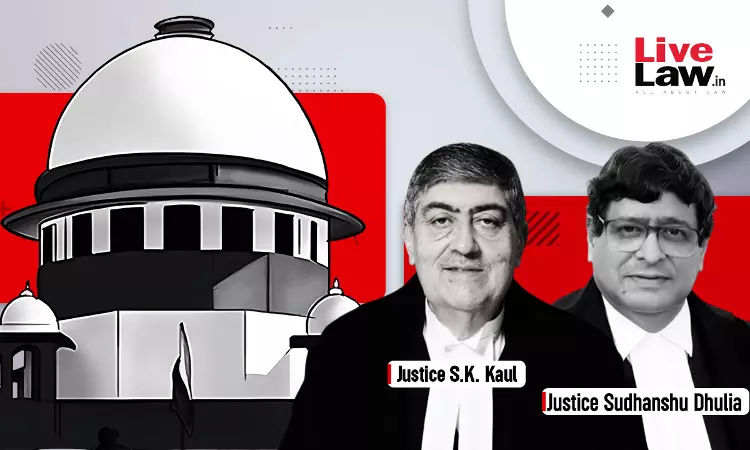

The Supreme Court on Wednesday dismissed a public interest litigation (PIL) petition seeking a ‘cooling off’ period of two years before any retired judge of a constitutional court can accept a post-retirement appointment.A bench of Justices Sanjay Kishan Kaul and Sudhanshu Dhulia was hearing a plea filed by the Bombay Lawyers Association with the objective of “upholding the independence...