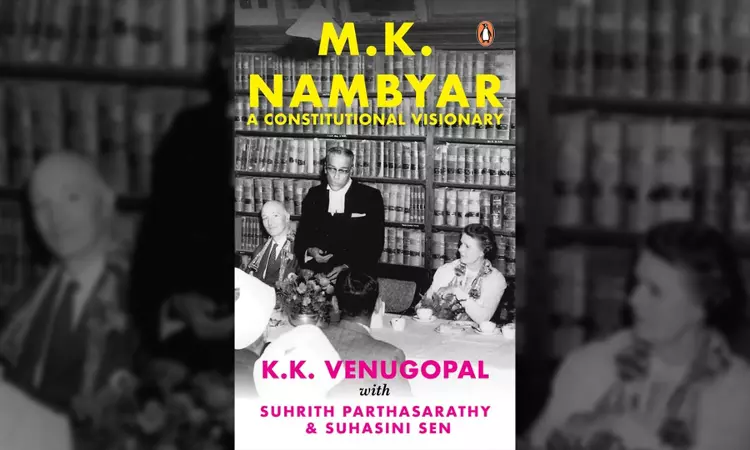

Book Review - M.K. Nambyar - A Constitutional Visionary

Nikhil Sanjay-Rekha Adsule

21 Dec 2023 10:58 AM IST

Next Story

21 Dec 2023 10:58 AM IST

Benjamin Disraeli, the thinker moots for reading biographies as they are life without theories. I would have accepted this theory of Disraeli earlier but hesitate to accept it in toto as a lived life may not always be laden with vapid theories but principles that illuminate a person, infact take away her out in the sunshine of real knowledge; as Plato explains in his Allegory of...