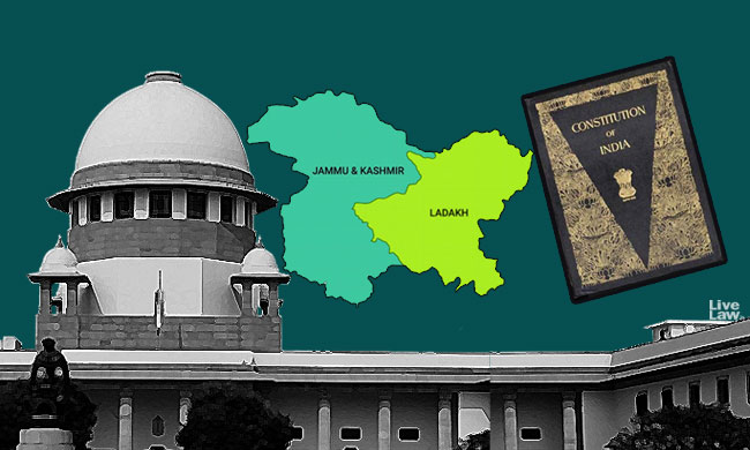

Judicial Abdication In Kashmir Habeas Petitions

Manu Sebastian

29 Aug 2019 7:55 AM IST

Has the SC in these cases done complete justice to its constitutionally assigned role of protector of fundamental rights?

The habeas corpus writ is known as the 'great writ of liberty', as it seeks the immediate protection of personal liberty from the excesses of State power.

But the orders passed by the Supreme Court on August 27 in two habeas corpus petitions concerning detentions in Kashmir do not reflect the spirit of this glorious writ.

One was a petition filed by Sitaram Yechury , general secretary of CPI(M), challenging detention of his party colleague M Y Tarigami , a four time MLA from Kulgam in the now dissolved J&K assembly. The second was a petition by Mohammad Aleem Syed, a law graduate in Delhi, seeking information regarding whereabouts of his parents in Anantnag, who he apprehended to be under detention.

In both these petitions, the SC 'permitted' the petitioners to travel to Kashmir on Government assistance to meet the detained persons.

Coming amidst the tight clampdown imposed in the J&K region (which is entering its 25th day), these orders have been welcomed with a sigh of relief by proponents of civil liberties. But one should not get carried away by such small offerings of liberty to fail to ask the larger question – has the SC in these cases done complete justice to its constitutionally assigned role of protector of fundamental rights?

It needs to be said that in these cases the Supreme Court failed in its role as the 'sentinel on the qui vive' of civil liberties.

The prime purpose of this writ is to obtain the production of an individual who is alleged to be in illegal detention(Habeas corpus literally means 'produce the body'). It is meant to provide an expeditious and effective remedy against illegal detention. So, when a writ of habeas corpus is sought, it is imperative that the Court asks the State if there is detention as alleged, and if yes, whether the detention is made on legal grounds.

Curiously, in both these petitions, the SC has not cared to ask the government these pertinent questions. There was not even a single query regarding detention and its grounds. The Court did not even issue notice to the Central Government in the cases.

At the same time, as if to maintain the veneer of a constitutional court, the Court 'allowed' the petitioners to travel to Kashmir to visit the detenus.

In the case of Yechury, the court said :

"On due consideration, we permit the petitioner to travel to Jammu & Kashmir for the aforesaid purpose and for no other purpose."

This permission was conditional on Yechury undertaking not to make the visit 'political'. The order added :

"We make it clear that if the petitioner is found to be indulging in any other act, omission or commission save and except what has been indicated above i.e. to meet his friend and colleague party member and to enquire about his welfare and health condition, it will be construed to be a violation of this Court's order."

It is baffling how the Court could impose restrictions on Yechury's fundamental right to travel by saying that it could be 'for no other purpose'.

In the case of Syed, the Court said :

"The petitioner shall be allowed to travel to Jammu & Kashmir; go to Anantnag; meet his parents and after ensuring their welfare, to report back to the Court on the next date fixed."

Thus, in a bizarre turnaround, the petitioners were sent to the detenus and asked to report to the Court. By making the exercise of rights conditional on the 'permission' from the Court, these orders have rewritten the meaning of 'fundamental' rights.

Instead of seeking an affidavit from the Government, the Court has chosen to task the petitioners with the duty of submitting to the Court reports regarding their visit.

As observed by the SC in a 1973 decision, the most characteristic element of the habeas corpus writ is its peremptoriness and "the essential and leading theory of the whole procedure is the immediate determination of the right to the applicant's freedom and his release, if the detention is found to be unlawful."

The whole object of proceedings for a writ of habeas corpus is to make them expeditious, to keep them as free from technicality as possible and to keep them as simple as possible, as observed by SC in Hadiya case judgment. The essential purpose of this writ is to swiftly determine if a person's detention is legal. To ascertain and ensure the well-being of the detenu is not its sole purpose. It is distressing to watch that the apex court going against the well-established principles of habeas corpus writ.

Delay in listing of the cases

In the listing of these petitions too, the Court did not show the urgency which a habeas corpus matter deserved.

Sayed's petition was filed on August 10, but was listed only on August 28.

In Yechury's case, a bench headed by Justice Ramana had passed a judicial order on August 23 to list the petition on August 26. But the petition was listed only two days later.

Similar casualness is visible in the way Delhi High Court is treating the habeas petition challenging the detention of Shah Faesel. On August 23, the Court adjourned the hearing of the petition till September 3, without even issuing a formal notice to the Centre. The Court declined to give an earlier date, saying the matter would take time and "it is not going to happen overnight".

The government narrative about the 'extraordinary situation' prevalent in Kashmir does not justify the Court's response in these matters. After all, judiciary is supposed to act as a check on the executive, and not its ally.

The general atmosphere of curfew imposed in the region cannot give the State a carte blanche to detain political opponents without legal grounds. Preventive detention is permissible only on constitutional grounds as per Article 22. So long as Articles 21 and 22 are in force, it is incumbent on the Court to enquire about the grounds of detention. Unfortunately, the Court has not performed that function.

The situation, in many ominous ways, seems a redux of the Emergency era Supreme Court, which produced the 1976 ADM Jabalpur decision. Refusing to issue habeas corpus writ for release of detenus on the ground that personal liberties can be suspended by State during emergency, the SC had observed in that infamous decision that detention was like a motherly punishment for a larger good.

The silence and abdication of the present judiciary in these matters also seem to be conveying the same message.