Is It Ethical For A Sitting Judge To Publicly Praise the Prime Minister?

Anurag Bhaskar

29 Feb 2020 10:32 AM IST

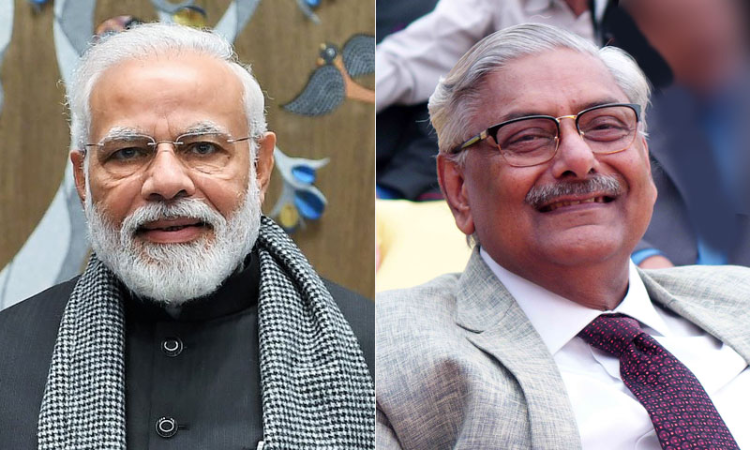

The Supreme Court of India was hosting the International Judicial Conference 2020 (22nd-23rd February) on the theme "Judiciary and the Changing World" to facilitate a dialogue of ideas between judges of India and those from abroad. However, the remarks made by Justice Arun Mishra in praise of Prime Minister Narendra Modi must have made the judges from over twenty countries (including United Kingdom and Australia) also reflect upon the themes of judicial ethics and propriety — which were not a part of the Conference's explicit agenda.

The Chief Justice of Australia, the President of the Supreme Court of United Kingdom, and other judges would have pondered among themselves over a very important question for judges all around the world : Is it ethical for an incumbent constitutional court judge to publicly praise the Prime Minister ?

What did Justice Arun Mishra say?

Delivering the vote of thanks at the inaugural function of the Conference, Justice Arun Mishra hailed Prime Minister Narendra Modi as "the versatile genius, who thinks globally and acts locally" and an "internationally acclaimed visionary". Justice Mishra made these remarks while expressing gratitude towards the Prime Minister for inaugurating the Conference.

The Chairman of Bar Council of India, Manan Kumar Mishra, has come out in support of Justice Mishra that the comments were made as a matter of courtesy. In order to contemplate whether the comments made by Justice Mishra were justified, we first need to understand the broader principles of ethics and propriety governing the judiciary.

Why do Ethics & Propriety in Judiciary matter?

Separation of power is a part of the basic structure of the Indian Constitution and in itself is a guarantee of judicial independence. The constitutional provisions of tenured office, conditions of service, etc. for constitutional court judges are safeguards provided to maintain this independence. However, independence of the judiciary — as held in several judgments — also comes with a duty of accountability, impartiality, and transparency.

An institution has to function within certain parameters and is governed by written rules and unwritten conventions and practices. This is where ethics come into picture. Judicial ethics, in simple words, refer to standards and practices to which members of the judiciary must be held. These ethics are necessary to maintain not only the constitutional system of checks and balances, but also the perception of it. In that sense, ethics to be followed by judges are not mere unsaid rules, but embody mandatory constitutional as well as institutional requirements necessary to maintain the legitimacy of the Indian legal system and public trust.

What do Judicial Ethics require?

The conduct of each individual judge must be in consonance with institutional ethics. A judge should not engage in any conduct which could blur the impression of judiciary as an institution of checks and balances. Judicial ethics require a certain level of restraint from judges in order to maintain public confidence in the impartiality and independence of the judiciary.

Therefore, in their professional and private relations with the other organs of the State or its representatives, judges must avoid any conflict of interest and must not be involved in any behaviour that might create a perception that the dignity of the judiciary in general is impugned. When judges speak, people listen, and their speech can inform the public about the role of the judiciary. Every action and word of theirs (spoken or written; inside or outside the court) must reflect correctly — as held in one judgment — that "they are determined to strive continuously to enhance and maintain the people's confidence in the judicial system".

Supreme Court's Own Ethical Parameters : Codification, Judgments & Practices

The principles of judicial conduct have been drawn up by the judges themselves. On May 7, 1997, the Supreme Court of India in its Full Court adopted a Charter called the "Restatement of Values of Judicial Life". One of the adopted values requires "every Judge" at all times to "be conscious that he is under the public gaze" and that "there should be no act or omission by him which is unbecoming of the high office he occupies and the public esteem in which that office is held". The Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct 2002, adopted at the Round Table Meeting of Chief Justices, crystallizes "Propriety, and the appearance of propriety" as one of essential elements necessary to "the performance of all of the activities of a judge". Ethics, propriety and accountability are inherent in both these institutional documents.

Moreover, in a number of judgments, the Supreme Court has itself emphasized on the necessity of ethics and has taken a strict stand against ethical violations by judges. In Daya Shankar vs. High Court of Allahabad (1987), the Hon'ble Supreme Court held that the judges "cannot act even remotely unworthy of the office they occupy". In High Court of Judicature for Rajasthan v. Ramesh Chand Paliwal (1998), the Court said that judges "have to live and behave like 'hermits' who have no desire or aspiration". It was also held, in the case of High Court of Judicature at Bombay vs. Shashikant S. Patil (2000), that the judges are "holders of public offices of great trust and responsibility".

Another important observation comes in Tarak Singh vs. Jyoti Basu (2005). The Supreme Court categorically held that judges must exercise "self discipline of high standards" as no other authority can impose a discipline on it from outside. Any aberration created by a sitting judge causes damage to the image of the judiciary. The Court therefore made it clear: "It is high time the judiciary took utmost care to see that the temple of justice does not crack from inside... It must be remembered that woodpeckers inside pose a larger threat than the storm outside."

During their tenures as Chief Justice of India, several judges warned against aberrations and violations in ethics from within the judiciary. Chief Justice R.C. Lahoti had once emphasized that "the judiciary to remain protected must be strong and independent from within" and this "can be achieved only by inculcating and imbibing canons of judicial ethics inseparably into the personality of the judges". Given the fact that the Supreme Court judges themselves lecture judicial officers from different parts of the country at the National Judicial Academy and State Academies, the following observation of Chief Justice SH Kapadia becomes highly relevant: "When we talk of ethics, the judges normally comment upon ethics among politicians, students and professors and others. But I would say that for a judge too, ethics, not only constitutional morality but even ethical morality, should be the base". Chief Justice TS Thakur had also reiterated that judicial ethics should never be compromised as aberrations occurring at any level could bring disrepute to the entire judicial system.

Therefore, the constitutional requirement of ethics in judiciary must be realized through the actual working of its functionaries.

Justice Arun Mishra's Comments : Whether Contrary to Judicial Ethics ?

The long-standing norms of judiciary behavior and ethics require that judges must be cautious of their role and responsibilities while engaging in public speech. They cannot be frivolous in the use of their words. Since their words whether inside or out of the court room carry far more weightage than an average citizen, the ethical obligation rests harder upon their shoulders.

Justice Mishra's comments extend beyond the basic formal courtesy. He could have certainly restrained himself from making those comments. Such remarks blur the perception of checks and balances for any external observer, especially for the judges from the international community attending the Conference. Comments of this nature — to repeat in the words of Chief Justice Thakur — have brought disrepute to the entire Indian Supreme Court and the legal fraternity before the international judicial community.

What Now?

When a popular judge of the United States Supreme Court, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, had made scathing comments on the then Presidential Candidate Donald Trump in 2016, she was widely criticized. Later, Justice Ginsburg publicly apologized for her remarks. As Manu Sebastian has aptly observed, "The unwritten code of judicial propriety envisions an invisible wall between judiciary and politics". For crossing this boundary, can we expect a similar apology here in India? Maybe. Maybe not.

It is requested to the Chief Justice of India that he will convey to his colleagues that comments in praise of politicians, especially the incumbent Ministers, are not welcomed at all. Justice Arun Mishra's remarks in praise of the incumbent Prime Minister must be condemned in the same manner as the legendary HM Seervai had openly criticized Justice PN Bhagwati for praising Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in a letter in 1980. After all, the Supreme Court itself held as recent as in November 2019, "To equate the actions of an individual which have no nexus with the discharge of official duties as a judge with the institution may have dangerous portents. The shield of the institution cannot be entitled to protect those actions from scrutiny. The institution cannot be called upon to insulate and protect a judge from actions which have no bearing on the discharge of official duty". By scrutinizing the actions of the judges, the judiciary as an institution will protect its own broader accountability function.

(Anurag Bhaskar teaches at Jindal Global Law School, Sonipat.)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of LIVELAW and LIVELAW does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.