Privacy In Times Of Corona : Problems With Publication Of Personal Data Of Covid-19 Victims

Soutik Banerjee and Devika Tulsiani

26 March 2020 12:49 PM IST

There are numerous problems with the publication of an online database consisting of personal data of the Covid-19 Victims

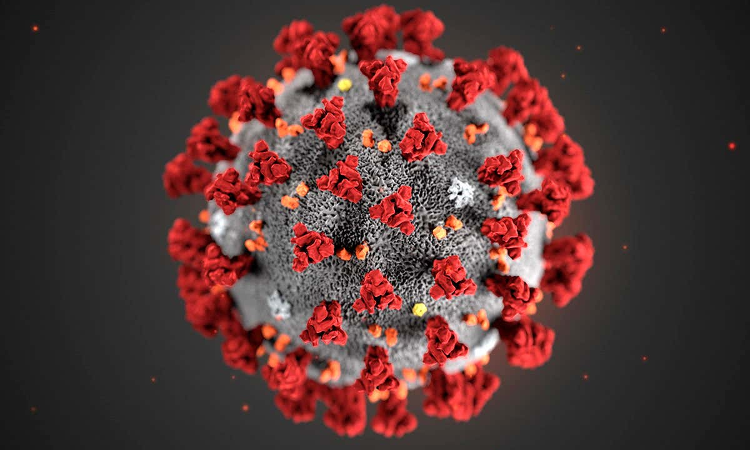

These are unprecedented times for independent India, where a public healthcare crisis has brought the world down to its knees. Perhaps the last time such global panic and fear prevailed was during the World Wars, a definitely human crisis of mammoth proportions. The debate on human culpability in the spread of the novel coronavirus Covid-19 has only begun and is likely to dominate international discourse and politics for some years to come. For now, the focus lies on prevention, mitigation and control of Covid-19, and towards this the various state governments and the Union government have taken a slew of measures.

Covid-19 has affected more than 4,25,000 people across the world, and has claimed over 19,000 lives. Traced to Wuhan district in China, Covid-19 has hit the European nations of Italy, Spain and France the worst so far, with each nation reporting over 500 deaths on a daily basis now. In comparison, the virus was late to arrive in India, with the first case reported only on 30 January 2020. As of today, the total number of affected persons as per official records is over 600, whereas the death toll is said to be at 10. The trajectory of the spread of Covid-19 in other countries suggests that India is entering the period when the spread of the virus is likely to explode, and in view of the impending crisis, strict measures have been taken to force social isolation by individuals other than those engaged in essential services.

On 23.03.2020, the Prime Minister of India announced at 08:00 pm that for the next three weeks, the entire country shall be placed under a lockdown, urging citizens to draw a "Lakshmanrekha" outside their homes so that the spread of the virus can be contained. Persons with symptoms of the virus are being screened and quarantined, and given the not so vibrant public healthcare system in India, all efforts are being made to contain the spread so that the least number of infected persons require treatment.

In light of the above, the State of Karnataka, presumably in good faith on 24.03.2020 has published an online database of persons who have been infected with Covid-19 or are in quarantine, with their personal residential addresses. This database has since then been circulated on social media and instant messaging platforms, and reportedly contains details of more than 14,000 persons from Bangalore alone. In contrast, the State of Kerala which was amongst the earliest hit Indian states, has protected the data pertaining to those under treatment for Covid-19 citing issues of privacy. This throws up an important question given the State's determination to prevent the community spread of Covid-19 : What happens to 'Privacy' in times of Corona?

The Right to Privacy has been recognised as a cardinal part of our Fundamental Rights by the apex court in Puttaswamy I and reinforced in Puttaswamy II. This right is not absolute and can be fettered by the State strictly according to the Constitutional mandate. It has been explained in the Puttaswamy judgments that,

"whenever challenge is laid to an action of the State on the ground that it violates the right to privacy, the action of the State is to be tested on the following parameters:

(a) the action must be sanctioned by law;

(b) the proposed action must be necessary in a democratic society for a legitimate aim; and

(c) the extent of such interference must be proportionate to the need for such interference."

The judgment in Puttaswamy II further elaborates on the doctrine of proportionality by enunciating four sub-components:

(a) A measure restricting a right must have a legitimate goal (legitimate goal stage).

(b) It must be a suitable means of furthering this goal (suitability or rationale connection stage).

(c) There must not be any less restrictive but equally effective alternative (necessity stage).

(d) The measure must not have a disproportionate impact on the right holder (balancing stage).

The step taken by the State of Karnataka in publishing the names and the residential addresses of the people infected by Covid-19 and those that have been quarantined, has prima facie infringed on the Right to Privacy of those citizens. The question that arises then is whether this measure can withstand Constitutional scrutiny as per the tests laid down by the Supreme Court in Puttaswamy.

The breach of a citizen's privacy, to be valid, must be sanctioned by a law that has been passed by the legislature. On perusing the relevant laws including The Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897, and The National Disaster Management Act, 2005, there seems to be no legal provision which provides for the personal data of the victims to be uploaded on a public database. This preliminary illegality notwithstanding, the State's action also falls foul of the test of proportionality.

An act by the government which infringes on the Fundamental rights of its citizens, in order to withstand the test of proportionality, must ensure that it is not excessive, in that there should not be any existing measures that are equally effective with a lesser degree of encroachment. Puttaswamy calls this the 'necessity stage'. The policy followed by various state governments until now has been to use indelible ink to stamp and brand those who have tested positive or have been quarantined. To further limit their contact with the public at large, some states have also marked their houses with pamphlets alerting visitors and ensuring public safety.

This action of the State of Karnataka presumably has a legitimate goal in mind, i.e. to curb and control the spread of Covid-19 by minimising person to person contact. Given that the State's main objective is that the people who have tested positive for Covid-19 do not come in contact with other people, it would seem that bodily branding and identification of homes completely achieved the said objective, and the publication of a database of victims is wholly excessive.

There are numerous problems with the publication of an online database consisting of personal data of the Covid-19 Victims. With no Data Protection law in place (which is a continuous violation of the mandate of the Supreme Court while upholding the constitutionality of the Aadhaar Act), the private information of these persons, without their consent is being released in the public domain and is vulnerable to misuse and abuse. This epidemic has also seen a rise in xenophobia, prejudice and racial violence, and there have been reports of hate crimes in that regard. Leave alone infected patients and quarantines persons, even doctors and nurses treating Covid-19 patients are reportedly facing hate, abuse and discrimination. This makes the Covid-19 patients and those in quarantine, their families and friends increasingly vulnerable.

Living in an era where information uploaded for public consumption on the internet is almost never capable of being completely removed, the personal information of those in quarantine for Covid-19 will outlive the present crisis and remain in the public domain. What then happens to the right of these persons to be forgotten on the internet, and what happens to their identity once it is reduced to an entry on a stigmatized database? Stigma, as we know from history, tends to far outweigh rationality and sagacity, and has a lifespan of its own.

It is often the tendency of States to consider civil liberties as dispensable in times of crisis, war or emergency. Some would argue that it is the right thing to do, and arguably the Constitution too recognizes this by providing for Articles 352-360 which envisages a very different society in times of emergency. Yet, in dealing with Covid-19, we must understand that civil liberties and rights are not at the mercy of the Executive, and the true test of our democracy is to be able to emerge out of Corona with the least possible deviance from normalcy. Normalcy, in the present context, is a mere reference to a constitutional state of being.

It is also the tendency of the government(s) to treat dignity and privacy as some sort of 'soft' right, which can be dispensed with as and when the Executive deems it necessary, as long as a claim of national or public interest is made. The absence of a data protection law, and the lack of teeth in the Hon'ble Supreme Court's judgment in the case of Kashmir Times' Editor, Anuradha Bhasin, where despite the Court's orders no immediate review of the restrictions in Kashmir was undertaken, are testament to the commitment of the Union government to protection of the right to privacy and dignity of individuals.

The reports of police action in uprooting the Shaheen Bagh protest site, as well as whitewashing of protest graffiti from public walls, even when the nation's priority is to expend resources to combat Covid-19, is perhaps a sign of things to come. With a clarion call for bold steps to fight an invisible enemy, when the citizenry bands together as a nation, we are often susceptible to acts of silencing dissent, and any criticism of a government action or absence thereof is seen as unpatriotic. Thus, a crisis of Covid-19 proportions serves as a breeding ground for aggressive nationalism.

As India battles Covid-19, let India not mutate into a state of unconstitutional existence. The virus will eventually leave us, but if civil liberties and rights are allowed to be abused by the Executive without any questioning or critique, decades of jurisprudence will have been eroded and confined to the dustbins of history