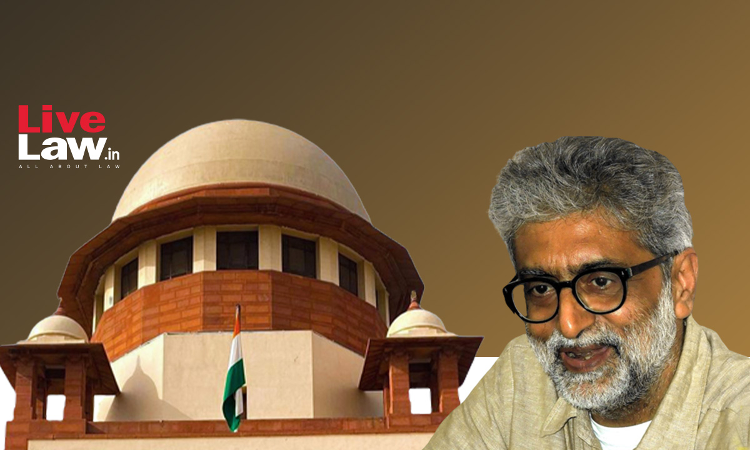

New Lessons From Navlakha’s Case: Why Some Usual Bail Conditions Need A Review?

Gaurav Mehrotra

16 Jan 2023 10:18 AM IST

The need to approach the Supreme Court to seek an exemption from the production of a solvency certificate to avail the house arrest granted to Gautam Navlakha is an expression of a deeper problem. Amongst the many conditions of house arrest permitted by the Supreme Court, there is a condition that requires him to submit a local surety of Rs 2 Lakhs. The order granting house arrest on 10th November 2022 reads as under:

To avail the facility of house arrest, the petitioner will provide local surety for a sum of Rs.2 lakhs (Rupees Two lakhs only) by 14th November 2022.

In the the present case, the court has been kind and graceful in modifying the condition of bail when the issue was brought to its notice and exempted him from filing solvency certificates of the surety. Navlakha appears to be well represented even in the formidable opposition by the Government at every stage. However, grant of exemption reflects two deeper problems that the courts may consider while granting bail.

First, the preference for a local surety. Many a time, a person is accused of committing a crime in non-home jurisdiction. A resident of Patna may travel to Mumbai and get arrested there for an offence registered in Mumbai. A condition of bail requiring him to present local surety residing in Mumbai to vouch for him could be a Himalayan task. Any judgment database is replete with examples where the condition of “local surety” is either sought to be relaxed or an appeal is filed against such a condition. In Moti Ram v. State of M.P., reported in 1978 SCC (Cri) 485 the Supreme Court frowned upon insistence on local sureties. The Court had held that:

“33. To add insult to injury, the Magistrate has demanded sureties from his own district. (We assume the allegation in the petition). What is a Malayalee, Kannadiga, Tamil or Telugu to do if arrested for alleged misappropriation or theft or criminal trespass in Bastar, Port Blair, Pahalgam or Chandni Chowk? He cannot have sureties owning properties in these distant places. He may not know any one there and might have come in a batch or to seek a job or in: a morcha. Judicial disruption of Indian unity is surest achieved by such provincial allergies. What law prescribes sureties from outside or non-regional language applications? What law prescribes the geographical discrimination implicit in asking for sureties from the Court district? This tendency takes many forms, sometimes, geographic, sometimes linguistic, sometimes legalistic. Article 14 protects all Indians qua Indians within the territory of India. Article 350 sanctions representation to any authority, including a Court, for redress of grievances in any language used in the Union of India. Equality before the law implies that even a vakalat or affirmation made in any State language according to the law in that State must be accepted everywhere in the territory of India save where a valid legislation to the contrary exists. Otherwise, an adivasi will be unfree in Free India, and likewise many other minorities. This divagation has become necessary to still the judicial beginnings, and to inhibit the process of making Indians aliens in their own homeland. Swaraj is made of united stuff.”

The said judgment has been followed consistently by the Supreme Court as well as by the High Court. In fact, following Moti Ram (Supra), the Hon'ble Bombay High Court in Subodh Prasad v. State of Maharashtra, 2010 SCC OnLine Bom 1320 that to avail furlough, by a way of government circular a condition of a local surety cannot be added when no such restriction is statutorily prescribed. The Bombay High Court reasoned as under

“15. The fact that the provisions in the Criminal Manual have been made very stringent in the backdrop of the experience of large number of absconding accused, to which reference has already been made hitherto, would be of no avail. Inasmuch as, the said provisions are relating to verification of solvency of sureties. The stipulations therein, in no manner, rule out the possibility of famishing solvent surety who is residing outside Maharashtra. We also cannot countenance the argument that it is always open to the appropriate Authority to impose additional condition to furnish “local solvent surety” only from Maharashtra to enable the prisoner/convict from other States to avail of furlough leave. Such requirement as aforesaid would not only result in imposing condition not envisaged by the Act and the statutory Rules but would also end up in being arbitrary and unjust and hit by Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution of India. For, a prisoner who has no relative or for that matter friends or acquaintances in Maharashtra State, can never be able to offer local surety and resultantly be denied of the legal right to avail of furlough leave. Further, a prisoner from outside State would avail of furlough facility to visit his/her relatives in other States…”

Second is the infatuation of criminal justice with money and property; and that being the pivotal basis to determine whether someone would jump bail. In the face of examples of rich business tycoons escaping from India to avoid the rigours of the criminal justice system, our judicial systems (especially the trial courts and the High Courts) need to pay more attention to other factors while granting bail than imposing a financial burden on the accused.

Navlakha, for example, could not avail the same immediately because the criminal justice system needed to verify the solvency of his sureties. Navlakha’s lawyers were able to secure a hearing to seek a modification of the bail conditions, but many poor under-trials facing similar situations may not be able to afford another hearing just to review the conditions of bail. Once bail is granted, the family of a poor accused often runs from pillar to post to secure cash for fixed deposit receipts or secure original papers of movable property. The Supreme Court has recently and rightly so, set aside a condition of pre-deposit of Rs. 7.5 lakhs to avail of the anticipatory bail.

Further, according to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) for 2020 and the Prison Statistics India 2020 report, undertrials make up over 76% of all the total prisoners in the country.

Also, in its 268th report, the Law Commission had observed that the powerful, rich and influential obtain bail promptly and with ease, whereas the masses comprising of the common poor people languish in jails. “The greatest of evils and worst of crimes is poverty” these words of George Bernard Shaw written more than a century ago seem most appropriate for those poor under trails who are languishing in jail not because of the crime that they have committed but because of poverty.

The surety for bail must not be set so high that it effectively amounts to a detention order. It should be proportionate to the means of the accused and the circumstances of the case. The judge should be under a positive obligation to inquire into the ability of the accused to pay.

The basic principle behind running jails is safety and security to society, and if in a case it appropriately appears that an accused is not a threat to the society, then courts grant them bail with reasonable conditions so that they may step out and earn their livelihood thus easing the burden on the public exchequer as the jails are run mainly on the taxes paid by the citizens of the nation,

At this juncture special mention of the Delhi High Court’s judgment in Ajay Verma v. Government of NCT of Delhi (WPC No. 10689/2017) needs to be made where the Delhi High Court had directed the District Judges to undertake a periodic review, and specifically held that “In case of inability of a prisoner to seek release despite an order of bail, in our view, it is the judicial duty of all trial courts to undertake a review for the reasons thereof.” The directions issued by the Delhi High Court deserve to be adopted and implemented widely.

Later, in another PIL was preferred before the Delhi High Court seeking the release of several undertrials who were languishing in jails in Delhi for not being able to arrange the surety. However, there are dozens of such cases in Delhi itself despite the directions in Ajay Varma (Supra) and that unless there is an institutionalised mechanism of period review, the situation would remain the same due to continuous confrontation of the poor with the criminal justice system. Hence, there is an urgent need to revisit the conditions that can and should be imposed while granting bail.

The author is a practicing advocate before the Allahabad High Court sitting at Lucknow.

Views are personal.