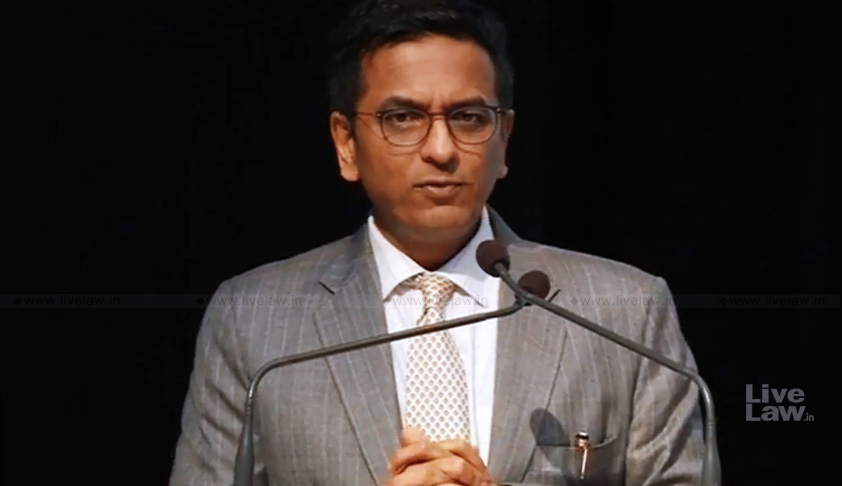

'Constitution Itself Is Feminist', Justice Chandrachud On Transformative Constitution & Feminism

Mehal Jain

7 Oct 2018 2:25 PM IST

Next Story

7 Oct 2018 2:25 PM IST

Agreeing that the Constitution is itself feminist, Justice Chandrachud articulated, “feminism is lot about disruption of social hierarchies and that is what the constitution intends to do. Transformation involves a disruption of the existing social structures”.O. P. Jindal Global University, in collaboration with National Law University, Delhi and Ambedkar University, Delhi, on...