Dissenting Opinions of Judges in the Supreme Court of India

Dr. Yogesh Pratap Singh, Dr. Afroz Alam & Akash Chandra Jauhari

5 April 2016 7:08 PM IST

Introduction

Traditionally, an empirical work on the dissenting opinions of Judges in the Supreme Court of India has been fairly limited. This may be attributed to the uncertainty of methodology to collect data and produce the most reliable results to understand the pattern of judgment delivery system in the Supreme Court. To overcome this limitation, the present paper aims to argue the case for an empirical study on how judges exercise their legal acumen to come to an independent conclusion on particular disputes which ultimately affect the health of Indian democracy. How free and capable is an individual judge in the bench to express his/her democratic of dissent? Is the concurrence to ‘aristocratic consensuses’ of the bench habitual? What is the level of dissent across the bench over the last six decades in Supreme Court of India? Which Justices dissent more frequently than others? Is there any regular pattern of voting amongst the Justices of the Court when Chief Justice is a part of the bench? What is the propensity of the judicial dissent which got recognition and contributed meaningfully to the development of law? To substantially explore these questions and empirically locate the trends, we have collected and analysed Supreme Court’s Judgments delivered from 1950 to 2014 using the source of All India Reporters (AIR) and Supreme Court Cases (SCC).

Dissenting Opinions in the Supreme Court of India

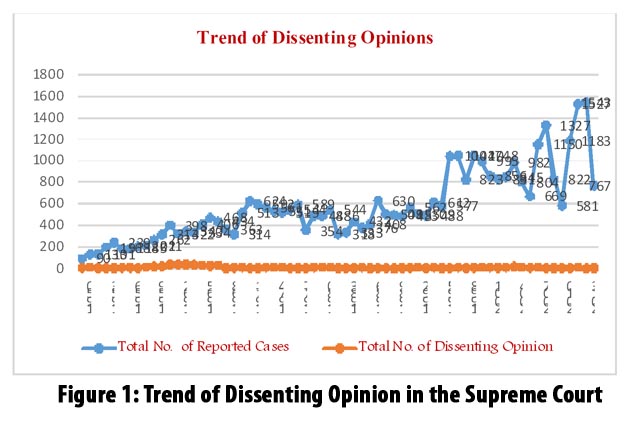

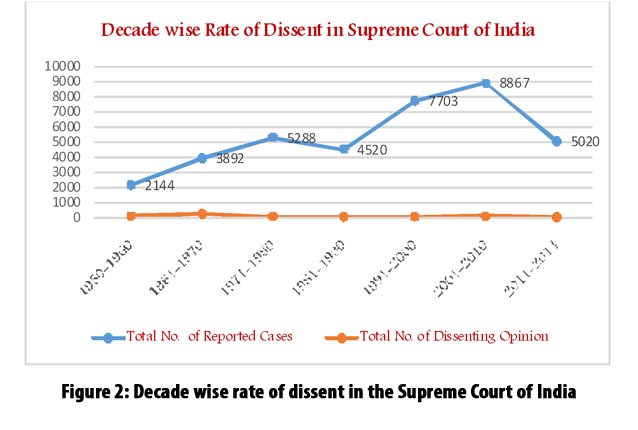

The value of free speech and expression gets strengthened when judges capably use it to arrive at different opinions- informed, effective and judicious. On many occasions we see the positive outcomes of these dissenting opinions on reforming the law and correcting the error of the majority opinion in the forthcoming judgments. However, in the judgment delivery system of India, our judges either concur or supplement the majority opinions in most of the cases. It does not mean that the free expression of dissent is nonexistent. But it is very occasional and declining at an unusual speed. It is clear when we look at Figure 1 and Figure 2 which provides general and decadal rate of dissent respectively in the Supreme Court of India.

The phenomenal decline in expressing dissenting opinions of the judges raises many questions on the credibility of the very institution of Supreme Court. Our observations of the trend are as follows:

- Figure 1 and 2 suggests that the first two decades the rate of dissent and number of dissents both are relatively good and particularly during 1961-1970 which gave us highest rate of dissents. In this phase, we witnessed some great dissenters like Justice A. K. Sarkar, Justice K. Subba Rao, Justice Hidaytullah, Justice J. C. Shah, Justice J.S. Mudholkar, Justice Vivian Bose and Justice J. L. Kapur to name a few.

- The sudden decline in the rate of dissent in the third decade perhaps indicates that judiciary was overshadowed either by the external forces (government) or by internal forces (influence of Chief Justice of India). This was the time when Mrs. Indira Gandhi came into power and the judicial appointments were heavily politicized. However, an eleven judge bench constitued at the beginning of penultimate decade snatched the power of appointment from the government and gave it to collegium system. But this collegium system failed to bring qualitative change in the judgment delivery of Supreme Court despite getting autonomy in the appointment of judges. Because, on the one hand, it did not bring any improvement in the quality of judgments. On the other hand, the velocity of dissent instead of improving seriously declined.

- The present trend of phenomenal increase in the constitution of two-judge bench by the Supreme Court is more alarming which further reduces the possibility of dissent.

- Finally, the rising workload of judges may also be responsible for the decline of disagreement in the bench. The strength of Supreme Court currently nowhere proportional to the rising workload of cases. Today the object of bench is to dispose of the matter rather than quality of judgment. But this approach is not justified in the light of very old common law principle that “justice should not only be done it must seem to be done.” The economic theory of judicial behavior also predicts that a decline in the judicial workload would lower the opportunity cost of dissenting and increase the frequency of dissent.

Dissent in the Chief Justice’s Bench

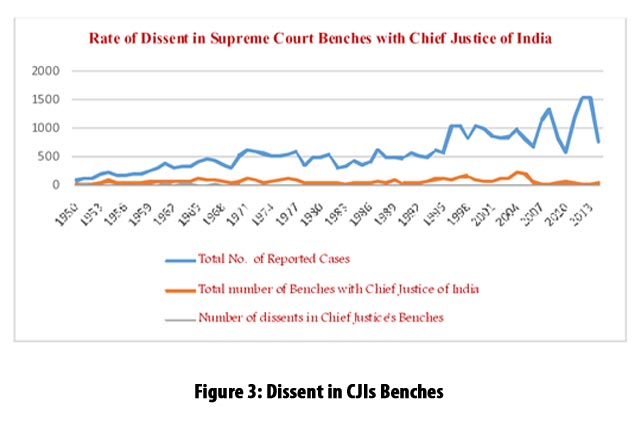

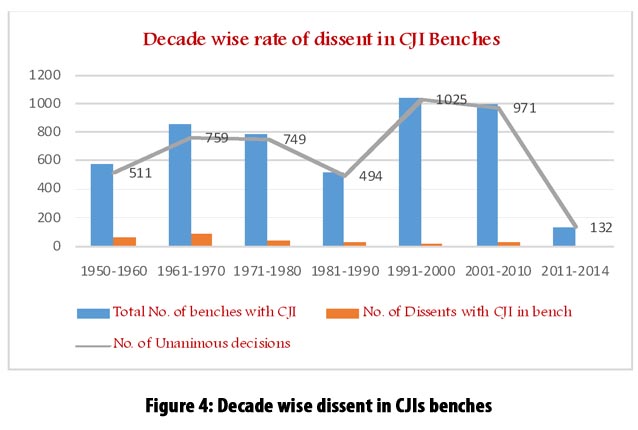

It is generally observed that the rate of dissent was very low when the Chief Justice himself is the part of the bench over the last sixty-five years (Figure 3). It is also surprising that no Chief Justice of India has expressed his dissenting opinions.

In the very first decade, what we found, the rate of dissent in benches of CJI was 10.97%. In the initial years of this decade, the rate of dissent was 31.25% in 1950, 31.42% in 1951 and 17.24% in 1952. This trend was almost similar in the second decade where rate of expressing dissent in CJI bench was found 10.60% (out of total 849 CJI benches, in 90 dissents were recorded)[ During 1950 to 1960, 89% cases were decided unanimously and this trend continued in the subsequent decade (1961-1970)]. In the year 1961 rate of dissent was highest i.e. 22.9% and lowest i.e. 3.57% was noticed in 1969. However, during 1971-1980, surprisingly the rate of dissent decreased significantly up to 4.22% (highest 10.52% in 1980, 10.20% in 1978 and lowest 1.27% was recorded in the year 1976). This decline continued during 1981-1990 and rate of dissent was recorded 4.07% (no dissent was recorded in the year 1986).

In the last two decades (1991-2000 & 2001-2010) the rate of disagreement in benches with CJI has gone down further up to 1.72% and 2.70% respectively. In the years, 1996, 2000, 2001, 2009 and 2010, not a single dissent was recorded in CJI’s benches. The present decade (2011-2014) is witnessing the abysmal rate of dissent in the CJI benches. No dissents have been recorded from 2011 to 2014 so far in any of the benches with Chief Justice of India.

The present declining rate of dissent in the Supreme Court decision making when Chief Justice is a part of the bench is also disquieting. Our observations of this trend are as follows:

- Some of the Chief Justices were able to create a democratic ambience in the bench where other judges were feeling comfortable to express disagreement and hence dissent rate was high for instance in first two decades and mainly in the years 1951, 1952 and 1953[During this period Indian Supreme Court was blessed with some democratic Chief Justices who created the ambience where dissent was flourished viz. Justice H.J. Kania, Justice Patanjali Shastri, Justice M.C. Mahajan, and Justice B.K. Mukherjee etc.]. Justice S. B. Sinha, one of the contemporary dissenters of the Indian Supreme Court argues that "Dissent means existence of democracy." He said, "Dissent means expression of own opinion by the judge. It does not affect the verdict. If dissent is not allowed, it means judiciary is not free."

- Conversely in the last two decades when velocity of dissent was found at its lowest level, we are forced to think that democratic elements were lost in last two decades and judges were not allowed to dissent. The fact that in the years, 1996, 2000, 2001, 2009 and 2010, not a single dissent was recorded in CJI’s benches. This trend continues in present decade also.

Following could be the possible reasons for the absence of dissents in CJI’s benches:

- It may be the persona of Chief Justice of India which restricts indirectly/directly other brother judges to express his/her disagreement in the bench.

- It is also possible that as the Chief Justice has a lot of administrative powers vested in him specifically power to constitute benches, he is in position to influence his brother judges not to raise question mark on his judgment or he constitutes benches of likeminded judges where possibility of dissent becomes almost zilch. Hence the possibility of bench hunting cannot be denied.

LEADING DISSENTERS IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA

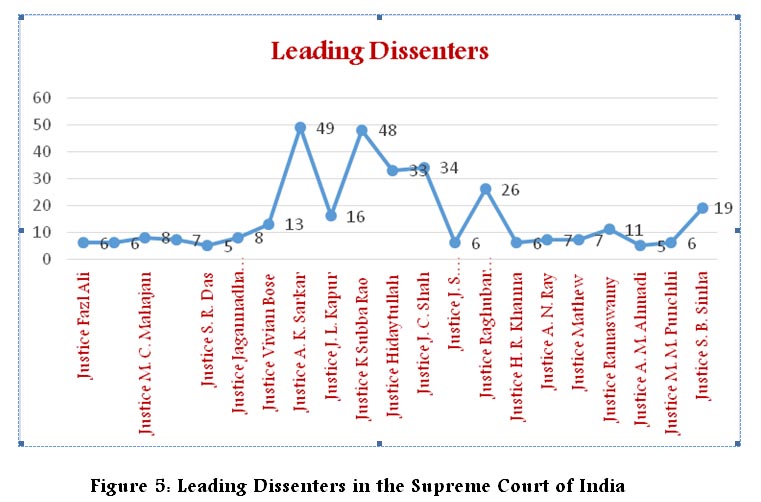

Like United States of America, Indian Supreme Court was also privileged to have some famous dissenters who in spite of all difficulties preferred to express their disagreements. For instance the one possible reason behind the high rate of dissent in the year 1950, 1951 and 1952 was the presence of one such judge i.e. Justice Fazl Ali who was known for his dissenting opinions[His dissenting opinions in A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras, Romesh Thaper v. State of Madras and Brij Bhusan v. State of Delhi are quite famous in the legal fraternity]. Similarly, Justice A. K. Sarkar and Justice K. Subba Rao made their presence felt in the legal academia through their dissenting opinions which is clearly visible in the data of years 1961, 1962, 1963 and 1964. Justice Hidaytullah and Justice J. C. Shah also contributed in this high rate of dissent. It would be pertinent to mention that Justice A. K. Sarkar has maximum dissents (49 dissenting opinions) to his credit [Figure 5].

We made the following observations while looking at the data on the leading dissenters of the Supreme Court:

The dissenting opinion displays a different insight, logic, craftsmanship, or some other similar quality which cumulatively create prestige and reputation of a judge. When we read about judicial giants like Justice Marshall, Justice Holmes, Justice Learned Hand, Justice Brennan or about Justice Michael Kirby and Justice Khanna and see their impact on legal system we cannot ignore their ability to write good and strong dissent. Perhaps we are lacking judges of that stature which we have witnessed in the past. In other words, we can safely argue that the quality of judges is seriously declining.

- Dissent is not prohibited but the environment in which good dissent can occur probably lacking in recent times. Data suggest that this decline started in the third decade, which was known for the “impact and influence” of Mrs. Indira Gandhi on all institutions including judiciary. She openly declared that “she wants committed judges”.

Judicial Dissents which got recognition with time

Undoubtedly, a judge writing dissenting judgment is making the law hoists the question of the acceptability of the reasoning adopted by the dissenting judge by the legislature, academia and judges. At the same time, the potency of a dissenting judgment is a matter for the future and depends on the direction which legal learning and experience dictate in the future. We have classified the famous dissents of the Supreme Court which got the recognition with time in following three categories.

- Dissents which got the recognition of Legislature: The first case in this category is New Maneck Spinning v. The Textile Labour, AIR 1961 SC 867. In this case, the dissenting opinion of Justice Subba Rao laid the foundation of the Payment of Bonus Act, 1965 and also adopted his line of argument that the payment of minimum bonus irrespective of profit or loss of employer. Second case in this category is ADM Jabalpur v. Shivakant Shukla AIR 1976 SC 1207. In this case, Justice Khanna delivered his famous dissenting opinion which took a strong stand that Article 21 is not the sole repository of the right to life and personal liberty, and such right could not be taken away under any circumstance without the authority of law, in a society governed by rule of law. Dissenting from the majority, he supported the view that the Presidential order of June 27, 1975 and the maintainability of the habeas corpus petitions proceed on different plane and one not affecting the other. Further, he held that it was open to question the legality of the detention orders and such petitions were maintainable despite that order.

- Dissents which got the recognition by the subsequent Supreme Court bench: The first case in this category is K. Gopalan v. State of Madras AIR 1950 SC 27. In this case the dissenting opinion of Justice Fazal Ali got recognized later in Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India which overruled the majority opinion of Gopalan and held that any law which deprives a person of personal liberty under article 21 should satisfy the requirement of Article 19. The court also accepted the influence of due process doctrine in Indian constitutional jurisprudence and any procedure must be “fair, just and reasonable”. Another case in this category was the dissenting opinion delivered by Justice Subba Rao in Radheyshyam Khare v. The State of Madhya Pradesh AIR 1959 SC 107 which laid down the premise of the law relating to principles of natural justice in the case of administrative bodies and subsequently recognized. The Supreme Court in the case of A. K. Kraipak v. Union of India AIR 1970 SC 150 held that the distinction between quasi-judicial function and administrative function has become quite thin and is being gradually obliterated. Therefore if the action of an authority affects the rights or the interests of a person and if it does, he must be heard. Thus, even before, Ridge v. Baldwin, , State of Orissa v. Dr. Binapani Dei, and Kraipak, Justice Subba Rao anticipated the correct law on the point and observed in his dissenting note in Radheshyam case that the concept of a judicial act has been conceived and developed by the English judges with a view to keep administrative tribunals and authorities within bounds. Unless, the said concept is broadly and liberally interpreted, the object will be defeated, that is, the power of judicial review will become innocuous and ineffective.

- Dissents which received appreciation by the legal academia: Under this category we place dissenting opinion of Justice Subba Rao in M.S.M. Sharma v. S.K. Sinha where his lordship observed that privileges are still archaic, uncertain and repressive and therefore cannot be given overriding effect on fundamental rights. Another leading which is worth mentioning here is Naresh Shridhar Mirajkar v. State of Maharastra, where sole dissention opinion of Justice Hidaytullah was able to raise doubts on the majority. His lordship observed that fundamental rights may be violated by the judiciary and hence any judicial action should also be amenable to writ jurisdiction. There are few other pronouncements which may be placed under this category where dissenting opinion received appreciation[See Dissenting opinion of Justice Bhagwti in Bhachan Singh v. State of Punjab, AIR 1980 898, dissenting opinion of Justice A.M. Ahmadi & Justice M. M. Punchhi in Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association v. Union of India, AIR 1994 SC 268, dissenting opinion of Justice Ruma Pal and Justice S. M. Quadri in TMA Pai Foundation v. Union of India, AIR 2003 SC 355, dissenting view of Justice S B Sinha and Justice S. N. Variava in Zee Telefilms Ltd. Union of India, AIR 2005 SC 2677 and dissent of Justice Dalveer Bahdari in Ashok Kumar Thakur v. Union of India, (2008) 6 SCC 1].

Conclusion

To conclude, we can safely argue that difference of opinions amongst judges is to be taken as healthy democratic trend which eventually strengthen the entire legal system. For example, it was the impact of the doubts raised by the two learned judges, Justice Hidaytullah and Justice J. S. Mudholkar in famous Sajjan Singh v. State of Rajasthan the whole matter was referred to larger bench of eleven judges i.e. Golak Nath v. State of Punjab, which held that Parliament cannot amend fundamental rights at all. This decision of the Supreme Court forced the Parliament to amend the constitution in order to nullify the effects. Finally, the issue was settled by thirteen judge bench in famous Keshvanand Bharati Case, which says that Parliament in exercise of its constituent power under Article 368 of the constitution, can change, amend, modify constitution including the chapter of fundamental rights, however they cannot change or destroy the ‘basic structure’ of the constitution. The doctrine of ‘basic structure’ once sounded by Justice Mudholkar in Sajjan Singh case became formalised with Keshvanand Bharati v. State of Kerala. It can be argued here beyond any doubt that the development of basic structure principle in India is the result of disagreement, which started in Sajjan Singh Case. Dissents are vindicated because the social, economic, or political environment changes. But the decline in dissent in the Supreme Court of India has put a threat to this institution.