Hohfeldian and judicial analysis of the punitive action against press by Karnataka Speaker

Namit Saxena

30 Jun 2017 11:41 AM IST

Last week the Karnataka Assembly speaker KB Koliwad found two journalists, Ravi Belagere and Anil Raju, guilty of publishing defamatory articles about the Speaker and other MLAs and sentenced each to one year’s imprisonment and INR 10,000/- Fine after a privileges committee for inquiry, headed by Yelahanka MLA SR Vishwanath, recommended punitive action against them. Raju of Yalahanka Voice had published an article on BJP MLA Vishwanath, while Belagere of Kannada weekly Hi Bangalore had published an article on Shiraguppa Congress MLA Nagaraj. In a follow-up article, the Yelahanka Voice had said Vishwanath was mentally ill. The articles are no longer in the public domain, therefore in this piece I seek liberty to deal with legislative privileges apart from commenting on merits of the abovesaid order. While writing this piece, the journalists have petitioned the High Court against the said order.

The last person to be imprisoned in this fashion by the British Parliament was Charles Bradlaugh in 1880. In India however, there are atleast three unfortunate precedents where similar instances have taken place. In 1992, editor Tarun Bharat was summoned and reprimanded for his article against the House. However, no punitive action was taken against his publication. In April 1987, Tamil weekly editor S Balasubramanian was sentenced to three months’ rigorous imprisonment for a cartoon. It mocked a member of the legislative assembly and a minister. Prior to that, the Tamil Nadu Assembly Speaker had sentenced the editor of Tamil traders’ journal Vaniga Otrumai, AM Paulraj, to two weeks’ imprisonment for an allegedly derogatory piece in July 1985. In 1979, Indira Gandhi was expelled from Parliament and imprisoned for breach of privilege, under a warrant signed by the Speaker, K S Hegde.

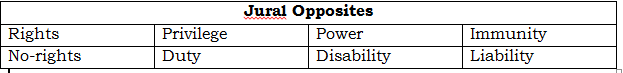

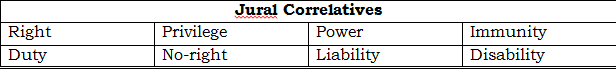

Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld (1879-1918), born in Claifornia authored the famous posthumous book Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning and Other Legal Essays (1919) and gave a powerful contribution to modern understanding of nature of rights and privileges. Hohfeld gave Jural Opposites and Jural Correlatives which can be tabulated as –

Hohfeld defined a right as a legal interest which imposes a correlative duty. Similarly a privilege imposes a corresponding and correlative no-right, power results in a correlative liability and immunity, in consequent disability. He further defined power to denote the control exercised by a person as regards his legal relations with another and immunity indicates one’s freedom from the legal power or control of another. Hohfeldian analysis has been accepted and adopted by the Supreme Court in India [see S.M.D Kiran Pasha v Govt. of A.P – 1990 1 SCC 328]

Part III of the Constitution broadly deals with 2 kinds of legal interests – Freedoms or liberties on citizens/persons and Prohibition on the Government from acting contrary to certain principles. Thus there is a hohfeldian duty on the state to secure every citizen. Legal interests granted by Part III therefore can be termed as Hohfeldian privileges instead of rights. The Constitution recognises the privileges of Parliament and state legislatures under Articles 105[1] and 194[2], respectively. Interestingly, the headings of the chapters in which these provisions appear themselves use the phrases ‘powers’, ‘privileges’ and ‘immunities’ separately. The legal interest conferred in this part is that of a privilege which imposes a correlative no-right of interference on others, including by legislative enactments. Article 105(2) therefore confers a hohfeldian immunity on members of Parliament while imposing a correlative disability from instituting legal proceedings on every other person. Further Article 105(3) authorises Parliament to enact legislations defining powers, privileges and immunities of each house. This power constitutes a hohfeldian power in itself and imposes a corresponding liability on every other person to abide by and respect the powers, privileges and immunities of Parliament as defined by law.

The freedom of speech within the legislature among others is codified (as a privilege) under these provisions while the legislatures enjoy same privileges as those of the House of Commons for other privileges and thereby remain largely uncodified. Nearly 67 years since the Constitution, neither the Parliament nor the legislatures have passed laws codifying privileges. Given the vague wording of the Constitutional provisions, the exact quantum and weight of privileges is uncertain. It is settled principle of law that power, exercise of power and conditions of exercise of power work in a parallel environment.

Difficulties arise when there is a head-on constitutional collision. E.g when legislatures (instead of judiciary) take penal action against the Press. In my view this is an encroachment on press freedom (a fundamental right guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a)). In past, questions relating to the chemistry of legislative privilege and the Right to Freedom of Speech and Expression have knocked the doors of the Supreme Court.

Amongst the earliest of such instances was the ‘Searchlight’ case (I) (M.S.M. Sharma vs. S.K. Sinha, AIR 1959 SC 395), which concerned the publication of expunged portions of proceedings of the Bihar Assembly. On being sentenced to imprisonment, the editor moved the Supreme Court, arguing that the publication was protected under Article 19(1)(a). Rejecting his stand, the Supreme Court held that the power of judicial review, applicable to ordinary law, could not be invoked to challenge an order made under Article 194, a Constitutional provision.

A few years later, one Keshav Singh was sentenced to one week’s imprisonment for breach of privilege of the Uttar Pradesh legislative assembly. Subsequently, a petition filed by him was listed before the Allahabad High Court. When the case was called, the Government advocate was not present; the petition was admitted and as the sentence was only one week, Singh was directed to be released on bail during the pendency of the case. The Assembly took offence to this and the stay order passed by the two judges was regarded as a breach of their privilege. Soon, the Assembly ordered its Marshal to arrest the judges and produce them before the Bar of the house. Subsequently, a full court (of 28 judges from the Lucknow and the Allahabad High Court) stayed the order of arrest. The matter went up to the President and Supreme Court before it was defused. The Supreme Court although held that Article 21 would be applicable even when Legislatures exercise their powers in respect of their privilege however, it also confirmed that the Freedom of Speech is subservient to legislative privilege.

In Raja Ram Pal v Hon’ble Speaker, Lok Sabha and Ors., (2007) 3 SCC 184, another Constitution Bench revisited the conflict. The Court held that the rights under Articles 20 and 21 could prevail over privileges under Articles 105 and 194. However, the Court omitted to lay down law as to the right under Article 19(1)(a).

Therefore, in light of the Hohfeldian analysis of right-duty-privilege and judicial precedents, there appears to be a lacuna in understanding and interpreting the width and ambit of parliamentary privileges when they tend to act against press.

[1] https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1251904/

[2] https://indiankanoon.org/doc/74909/

Namit Saxena is a Lawyer practicing in the Supreme Court of India.

[The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of LiveLaw and LiveLaw does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same]