In Defence Of The Offensive

Shalaka Patil

22 March 2018 10:43 AM IST

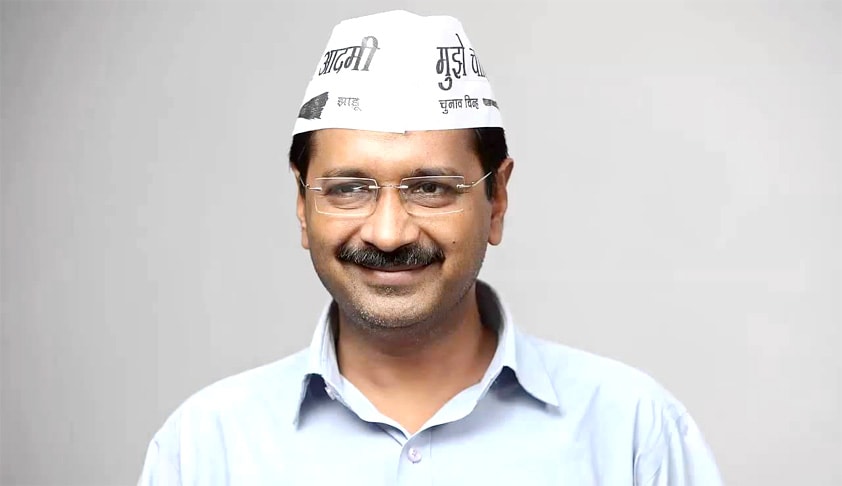

While many detractors of the AAP sneered at Kejriwal’s “backtracking” for apologizing to politicians Nitin Gadkari, Kapil Sibal and Bikram Singh Majithia in the criminal defamation complaints filed against him, few realize that this was a political masterstroke on his part. As Atishi Marlena notes in her piece, this was Kejriwal’s way of getting the cases out of the way to focus on real work. Criminal defamation complaints as intimidation tactics are common in politics and against the media. This piece examines the law on criminal defamation in India and why it has no place in India of the 21st century.

Section 499 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC) defines the “crime” of defamation as an imputation made or published that concerns any person which must have an intention to harm or the person making such imputation should know or have reason to believe that harm will be caused to the reputation of such person. The explanations to the provision then go on to state (a) you can defame a dead person, (b) you can defame a company or even an “association” or “collection” of persons, (c) you can defame even in irony or (d) it is defamation if your statements lower the “moral or intellectual character” of a person, lower his caste or calling, credit or imply that the person’s body is in a “loathsome” or “disgraceful” state. In other words, it is evident that this law was drafted over a century ago and other than being loathsome and disgraceful, it may well be criminal defamation to call your grandmother fat.

The punishment for such criminal defamation, per Section 500 is fine or simple imprisonment up to 2 years or both. The offence is bailable and a first class magistrate can try it. The offence is compoundable, meaning thereby that if the accused admits to the crime then she is acquitted on the basis that instead of punishment, the offender can bargain for an acquittal by payment of amounts determined by the court, tender an apology and such.

The provision also provides for 10 exceptions of what does not amount to defamation such as truth published for the public good, the conduct of a person relating to a public question, court reporting or comments on merits of a case, expression over a public performance etc. These exceptions seem to suggest that a journalistic exposé or a political speech would not fall within the realm of criminal defamation. The exceptions, however, set an unrealistically high standard. For example, some courts in India have held that to take the defence of the first exception, the statement must be wholly (and not partly) true and must be made for public good. The subjective satisfaction under the standard can get more and more granular when examining the exceptions under the provision. For example, when discussing the ninth exception, the Supreme Court in Chaman Lal v. State of Punjab has noted the requirement of showing good faith and that it should be shown that the utterance was made without malice, that it was made with due care and investigation, the circumstances under which it was made etc. All of these standards can be difficult to prove in a trial. The burden of proof of establishing these exceptions is on the defendant once the complainant has placed the allegedly defamatory material on record.

The law of criminal defamation has been globally criticized (and abandoned in many countries) since these cases are used for the opposite purpose for which the law was intended – to chill speech, used often as a counterblast. But these cases have the best currency in journalistic and political spheres where a gag order has the ultimate impact of jettisoning a story even before it begins. The problem is exacerbated because of the subjective nature of the law and the only evidence of “defamation” at least at the prima facie stage is that fact that a particular statement was made which the complainant views as defamatory. The veracity of the statement is established only at the trial stage and by then the defendant has been sufficiently worn out, the effect of chilling speech having been achieved.

The Supreme Court in the case of Subramanian Swamy v. Union of India , however,did not think that Sections 499 and 500 (as also Section 199 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973) impinged upon the freedom of expression under Article 19 of the Constitution, finding that the law was a reasonable restriction on the right to free speech. In this batch of petitions which challenged the vires of the law (the petitioners included Rahul Gandhi, Arvind Kejriwal, Subramanian Swamy and others) under Article 32 of the Constitution, the petitioners argued that under Article 19 (2) of the Constitution a law criminalizing “defamation” was not a reasonable restriction to freedom of expression since such a law was not narrowly tailored. The petitioners argued that the restriction imposed in relation to “defamation” must be read in conjunction with the words next to defamation [in Article 19 (2)], being “incitement to an offence” meaning thereby that material may be treated as defamatory only if it incites offence or has the potential to cause public disorder. On this basis, it was argued that the law of criminal defamation as it presently stands in the IPC is not a permissible reasonable restriction since it has no nexus to public order and ought to be struck down. The Supreme Court, however, was of the view that “defamation” being unambiguously stated in the restriction ought not to be restrictively read and that the criminality of defamation may not be derived only if it incites an offence. The petitioners also contended that the law of criminal defamation did not serve any public interest but instead served private interests. The court, however, found that the protection of rights of individuals would serve the public at large. As to the argument of the petitioners that the law was pre-constitutional and has no place in the present day, the Supreme Court was of the view that the right to safeguard one’s reputation is enshrined in Article 21 of the Constitution and thus both these fundamental rights have to be balanced. On this basis, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of Sections 499 and 500 of the IPC.

This lengthy Supreme Court decision (aside from its wearying, stream of consciousness sort of unending prose) was countenanced on the premise that a person’s right to guard her reputation is important enough to restrict the fundamental right of free speech. If that is to be taken as true, one would assume that cases involving criminal defamation have, as their primary purpose, safeguarding hallowed reputations. Given the nature of the offence, every case will obviously exhibit this as the ostensible purpose. However, regardless of the decision of the Supreme Court, in reality, how has the law of criminal defamation been invoked?

I ran a search over a sample of 20 reported cases of criminal defamation and that too only those before the Supreme Court. This sample size was large enough with a view to confirm some assumptions about the use of this law and small enough to be manageable. The sample was taken between the years 1962 to present day to cover a wide period to examine if there was any change in the nature of cases under this provision over the years.

Criminal defamation cases from the sample could be divided into three broad categories – Cases against the media, political cases and personal dispute cases. A vast majority (over 60%) of the sample complaints were those filed against the newspaper or broadcast media editors and publishers for coverage either against public officers, politicians or individuals in positions of power. From this, it can at least be surmised that the law gets actively used against media publication, often in terrorem. Some cases were also filed in a political context between individuals from opposing political factions for statements made during public speeches. A very small, third category were personal cases such as those in the realm of statements that may have hurt a religious community’s sentiment, statements made regarding criminal complaints filed that were later not prosecuted, marital disputes or disputes between business rivals etc.

In a number of cases filed against publications, members of editorial teams invoked Section 7 of the Press and Registration of Books Act, 1867 which provides a legal presumption (which may be controverted) that the name of the editor provided in a newspaper is sufficient evidence of such person being an editor and/or printer and/or publisher of the publication of that given title. On this basis, parties to proceedings have sometimes argued that as sub-editors or regional editors or chairpersons of the publication, they ought not to be prosecuted since they had little to do with the actual publication of an allegedly defamatory piece. But this argument has not always been successful, such as, for example in the Supreme Court’s 2017 decision in Mohammed Abdulla Khan v. Prakash K where the owner (not editor) of a Kannada newspaper was not exempt from trial.

In cases involving an offence against a minister, a public servant, the President of India, a Governor etc. in the performance of public functions, Section 199 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 applies and a Sessions court can take cognizance on the public prosecutor’s written complaint. Such a complaint requires the sanction of the State or the Central Government as the case may be and the Sessions court can take cognizance only when the complaint is filed within six months of the offence. These conditions / safeguards are however not available in complaints involving private citizens making it easy to file complaints that go right up to the Supreme Court, whether the case involves imputations relating to the “chastity of the wife” (words in the judgment, not mine) or allegations involving the pouring of kerosene and destroying 9 coconut trees. The use of the law of criminal defamation has been wide-ranging and in manners that would not even have been contemplated by our century-old IPC. When a criminal trial can take anything between 2-5 years or even more, it is no surprise then that Kejriwal chose to save legal costs, apologize and get on with business.

The old relics of laws to safeguard “reputation” and “honour” are a ruse from our colonial past. They were introduced in the British era as a means to quell dissent against the government and were not expected to survive in free India. 158 years later, however, the law still remains. In a trigger-happy country that is easily offended, having this law on our books is the equivalent of a toddler with a time bomb.

The author is a lawyer based in Bombay.

[The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of LiveLaw and LiveLaw does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same]