Is Resolution By Faridabad Distt Bar Assn Barring ‘Outstation’ Advocates Valid?

Advocate Namit Saxena

18 Jun 2018 12:49 PM IST

The District Bar Association, Faridabad, recently passed a resolution that an outstation advocate will not be allowed to appear in Faridabad courts unless he is accompanied by a local counsel. A drastic step to stop members of the fraternity from appearing in courts! In my view the resolution is, however, legally sustainable although it deserves to be withdrawn at the earliest. Let us see, how the resolution is legally acceptable.

The Advocates Act, 1961 carries within its fold, a dedicated chapter (Chapter IV – Section 29-34) on ‘Right to Practice’. Section 29 holds that there is only one class of persons entitled to practice the profession of law, namely, advocates. The expression ‘profession of law’ has been held to include both litigation and non-litigation matters [See Bar Council of India v AK Balaji]. Section 30 [brought into force only from June 15, 2011] states that subject to provisions of the Advocates Act, every advocate whose name is entered in the state roll shall be entitled as of right to practice throughout the territories of India. Furthermore, Section 33 lays down that subject to provisions of the Act or any other law for the time being in force, no person shall be entitled to practice in any court or before any authority or person unless he is enrolled as an advocate under the Act.

Therefore, the advocates enrolled with a state bar council have a right to practice. The right to practice also borrows substantial power from Article 19(1(g) of the Constitution which grants a fundamental right to practice any trade or occupation. The right u/s 29, 30 and 33 read with Article 19(1)(g) is however not absolute. The right to practice is subject to Article 19(6) and Article 225 of the Constitution and Section 34 of the Advocates Act. Article 19(6) lays down certain reasonable restrictions on Article 19(1)(g). Article 225 grants power to high courts to frame rules and Section 34 of the Advocates Act holds that a high court may make rules laying down the conditions subject to which an advocate shall be permitted to practice in the high court and the courts subordinate thereto.

In NK Bajpai v. Union of India [(2012) 4 SCC 653], the Supreme Court made it clear that right to practice can be regulated and is not an absolute right which is free from restriction or without any limitation.

There are two rules framed by the Allahabad High Court which deserve special attention at this juncture. As per Rule 3, an advocate who is not on the Roll of Advocates or the Bar Council of the state is not allowed to appear, act or plead in the said court unless he files an appointment along with another advocate who is on the Roll of such State Bar Council and is ordinarily practicing in that court. Rule 3A puts a further rider for appearance of an advocate in the high court at Allahabad or Lucknow inasmuch as an advocate who is not on the Roll of Advocates for Allahabad cases at Allahabad and for Lucknow cases at Lucknow is allowed to appear, act or plead at Allahabad or Lucknow, as the case may be, unless appearance is put in along with a local advocate. Notwithstanding the above, he can still be allowed to appear after obtaining the leave of the court.

These two rules were challenged which reached the doors of the Supreme Court finally. In Jamshed Ansari, the Supreme Court held that rules are regulatory provisions and do not impose a prohibition on practice of law. It further held that Section 30 is subject to Section 34 and there is no absolute right to practice. It also made note of Section 32 of the Act which permits any court to allow any person to appear before it after taking permission.

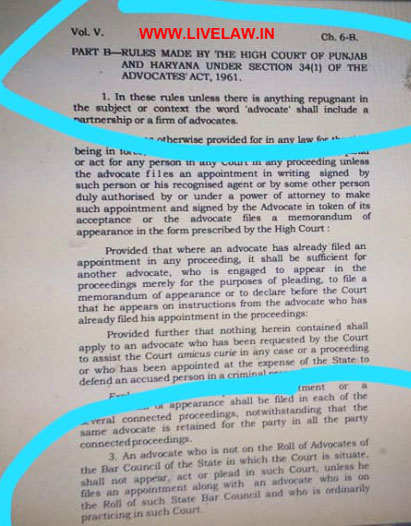

The legal position is quite clear. The high courts are empowered to lay down necessary conditions on the right to practice as the right is not absolute. A provision verbatim identical to Rule 3 of Allahabad High Court Rules can be traced to Rule 3 of Chapter 6B of the Rules framed by the Punjab and Haryana High Court. Therefore to act, plead or appear in any court in Haryana, one needs a local counsel who practices there and is enrolled with the State Bar Council.Advocates enrolled with the same State Bar Council cannot be treated as ‘outstation advocates’ and cannot be stopped from appearing.

However, some high courts like the Delhi High Court allow any advocate to act and appear irrespective the State Bar Council with which he or she is enrolled.

Namit Saxena is a practicing Lawyer at Supreme Court of India. He is the revising c0-author of Mulla CPC AND RatanLal DhirajLal Cr.PC