Law As Tool For Social Change : Examples From Karunanidhi

Manu Sebastian

9 Aug 2018 10:57 AM IST

The legislative changes piloted by him are notable, as they are illustrative of the power of law to act as a catalyst for social change.

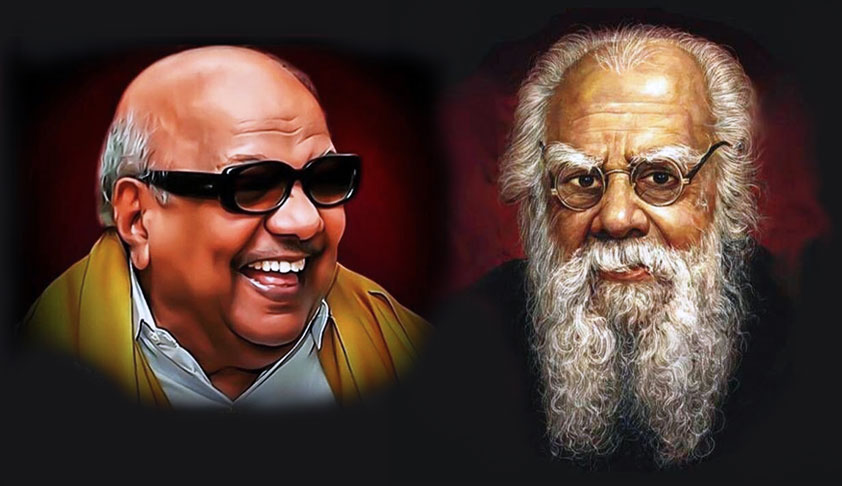

Five-times CM and president of Dravida Munnetra Kazhakam(DMK) Party Muthuvel Karunanidhi, who passed away on August 7, rode to power on the wave of Dravidian movement. The Dravidian movement powered by the thoughts of Periyar E.V Ramaswamy started off as an attempt to assert Tamil cultural identity; gradually it gained more ideological depth under the guidance of Periyar, to become a radical-reformist movement based on rationalism, atheism, equality and social justice. Periyar’s clarion call for the destruction of upper caste hegemony, and restoration of equal status of backward castes, triggered off the ‘self-respect movement’. Periyar carried out the translation of Dr.Ambedkar’s work “Annihilation of Caste” in Tamil and cited Ambedkar in several of his writings and speeches. Dravidian politics helmed by C.N. Annadurai and later by his protégé Karunanidhi drew from the well of thoughts of Periyar.

The astute administrator in Karunanidhi realized the power of law to advance reform. Certain legislative moves made during his tenure demonstrate how law can be used as an instrument of social change, as propounded by the sociological school of jurisprudence. Despite criticism about his brand of politics, at least during the later phase, his legislative changes are worthy of discussion.

Immediately after DMK got to power for the first time in 1967 under the leadership of C.N.Annadurai, they put into action their intentions to disrupt the social status-quo to further Dravidian ideology. Karunanidhi was a minister in the cabinet of Annadurai. First thing Annadurai did – change of name of the State as Tamil Nadu from Madras by enacting The Madras(Alteration of Name Act) 1968 – was symbolic of asserting Tamil sub-nationalism by cutting off ties with the colonial past. A more significant change during Annadurai’s tenure was the amendment of Hindu Marriage Act 1956, as per the Hindu Marriage(Tamil Nadu Amendment) Act 1967. By this amendment, Tamil Nadu became the first state to legalize “self-respect” marriages conducted without a Brahmin priest. The amendment introduced Section 7A in the principal Act, permitting “suyamariyathai”(self-respect) and “seerthiruttha”(reformist) marriages as legal when solemnised in the presence of friends, relatives or any other person by exchanging garlands or rings or by tying of mangalsutra or by a declaration in language understood by both the parties that they accept each other to be their spouses. This was putting the “self-respect movement” of Periyar into legislative action.

When Annadurai died in 1969, Karunanidhi became the CM, and carried forward the vision of his ideological mentors.

Changing hereditary appointment of ‘Archakas’ in Temples.

A revolutionary move by Karunanidhi after he became CM was bringing in legislation to change the rule of hereditary appointment of ‘archakas’ in temples, which had kept away several castes from doing priestly functions in temples. This was done by way of Tamil Nadu Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments (Amendment) Act 1970. Section 55 of the Tamil Nadu Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments 1955 had given recognition to the hereditary appointment of archakas, by stating that “in cases where the office or service is hereditary, the person next in line of succession shall be entitled to succeed”

The 1970 Amendment introduced by Karunanidhi government changed this rule, by adding sub-section(2) to Section 55 stating “No person shall be entitled to appointment to any vacancy merely on the ground that he is next in the line of succession to the last holder of office”. As the objective of the Amendment, it was stated that the hereditary principle of appointment of office holders in the temples should be abolished and that the office on an archaka should be thrown open to all candidates trained in recognised institutions in priesthood irrespective of caste, creed or race

A group of hereditary archakas and mathadhipathis approached the Supreme Court challenging this amendment as infringing their right to freedom of religious belief under Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution of India. This was considered by a Constitution Bench, resulting in the landmark decision Seshammal v.State of Tamil Nadu AIR 1972 SC 1856, which explains the scope of state interference in religious affairs under Articles 25 and 26 so as to provide for social reform.

The Court repelled the challenge against the constitutional validity of the Amendment. It was held that appointment of archaka was a secular function, upon which the State can interfere as per Article 26 of the Constitution. Hence, the Amendment was upheld as not interfering with any religious function or practise protected by Article 25. At the same time, the Court held that in a Saivite or a Vaishnavite temple the appointment of the archaka will have to be made from a specified denomination, sect or group in accordance with the directions of the Agamas governing those temples.

Giving equal coparcenary rights to Women

As per the Hindu Succession Act, 1956 enacted by the Parliament, daughters had no equal coparcenary rights in the ancestral property. They also had no right to seek for partition.

This discriminatory provision in the Central Act was amended, when Karunanidhi became CM during 1989. The Hindu Succession(Tamil Nadu Amendment) Act 1989 introduced Section 29A in the principal Act providing equal rights to daughters in coparcenary property. The newly introduced provision had a non-obstante clause, giving it overriding effect over Section 6 of the principal Act, which excluded daughters from coparcenary share. The Amendment also enabled daughters to seek partition of property. This amendment was in furtherance of Periyar’s thoughts on gender equality.

It took further 16 years for the Parliament to remove the discriminatory provisions, when it enacted the Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act in 2005, by which provisions similar to the 1989 TN Amendment were included in the principal Act. Perhaps, Karunanidhi was someone who thought ahead of time.

Further changes in rule of appointment of ‘archakas’

After assuming power in 2006, the DMK government under Karunanidhi attempted to bring in further changes in the rule of appointment of temple archakas. Although the 1970 amendment had abolished the hereditary rule, several castes were still excluded from appointment of archakas due to prescriptions in agamas.

In 2002, the Supreme Court had held that the appointment of a non-Brahmin as a priest in a temple did not violate the religious rights of a Brahmin priest under Article 25 and 26(Adithyan v. Travancore Devaswom Board AIR 2002 SC 3538).

Taking a cue from his judgment, the DMK government issued a government order on May 23, 2006 stating, “Any person who is a Hindu and possessing the requisite qualification and training can be appointed as Archaka in Hindu temples". The order made explicit reference to the SC decision in Adithyan. Also, an Ordinance(since lapsed) was brought in to further amend the Tamil Nadu Hindu Religious Institutions Act to state that no custom or usage will stand in the way of appointing a qualified person as archaka.

The Explanatory statement to the Ordinance indicated the purpose behind further amendment of S.55(2) in the following terms.

"Archakas of the Temples are to be appointed without any discrimination of caste and creed. Custom or usage cannot be a hindrance to this. It is considered that the position is clarified in the Act itself and accordingly, it has been decided to amend S.55 of the said Act suitably”

This move was challenged in the Supreme Court, which was considered by a two judges Bench of Justice Ranjan Gogoi and Justice N.V Ramana. The Court did not invalidate the Government Order, stating that its validity can be determined only on a case to case basis. It was held that the exclusion of some and inclusion of a particular segment or denomination for appointment as archakas would not violate Art.14 so long such inclusion / exclusion is not based on the criteria of caste, birth or any other constitutionally unacceptable parameter. The Court also emphasised the importance of Agamas and held that appointment has to be in consonance with Agamas. It was held that so long as the injunctions in Agamas were not contrary to Constitutional parameters, they have to be deferred to.(Adi Saiva Sivachariyangal Nala Sangam v. State of T.N. AIR 2016 SC 209)

In 2008, Tamil Nadu became the first state to evolve a policy for rights of transgenders, when his government set up Tamil Nadu Transgender Welfare Board. This was years before the Supreme Court declared the rights of transgenders in NALSA judgment in 2014.

The political legacy left behind by Karunanidhi is debatable, and he is severely criticised for his seeming descent into opportunism in coalition politics and perpetuation of rule by dynasty. Nevertheless, the legislative changes piloted by him are notable, as they are illustrative of the power of law to act as a catalyst for social change.

Manu Sebastian is a lawyer at High Court of Kerala.[The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of LiveLaw and LiveLaw does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same]