All You Need To Know About Prosecution Sanction [Part-II]

Justice V.Ramkumar

22 Jun 2017 2:15 PM IST

![All You Need To Know About Prosecution Sanction [Part-II] All You Need To Know About Prosecution Sanction [Part-II]](https://www.livelaw.in/cms/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Justice-Ramkumar.jpg)

E SECTION 197(1) Cr.P.C DISSECTED AND DISMANTLED

- Prosecution sanction either by the Central Government or by the State Government under Section 197 Cr.P.C is a condition precedent for taking cognizance of an offence by a criminal court against a Judge, Magistrate or public servant only if –

| 1 | he is removable from his office either | ||

| i) | by the Government, OR | ||

| ii) | with the sanction of the Government, | ||

| AND | |||

| 2 (a) | i) | he is employed in connection with the affairs of the Union | |

| OR | |||

| ii) | he is employed in connection with the affairs of a State | ||

| OR | |||

| (b) | (i) | he was, at the time of commission of the alleged offence employed in connection with the affairs of the Union | |

| OR | |||

| AND | ii) | he was, at the time of commission of the alleged offence, employed in connection with the affairs of a State | |

| 3 | the alleged offence was committed by him while acting or purporting to act in the discharge of his official duty. | ||

Prosecution sanction will be necessary only if 1 , 2 and 3 above co-exist. In other words, if any one of 1 to 3 above is absent then sanction to prosecute the accused is not necessary. Similarly since 2 (b) above uses the words “was at the time of commission of the alleged offence, employed” prosecution sanction under Section 197 Cr.P.C is necessary even if at the time of taking cognizance of the offence, the Judge, the Magistrate or the Public servant, has ceased to hold office or has retired from service. But the position under the P.C. Act is different.

E1(a) Who is the sanctioning authority u/s 197(1) ?

- In the case of a Judge, Magistrate or Public Servant falling under situation 2 (a)(i) or 2 (b)(i) above, the prosecution sanction is to be accorded by the Central Government. In the case of a Judge, Magistrate or Public Servant falling under situation 2 (a)(ii) or 2 (b)(ii) above, the prosecution sanction is to be accorded by the State Government. But where the President of India by Proclamation issued under Article 356(1) of the Constitution of India has assumed to himself all or any of the powers of a State Government, then by virtue of the proviso to Sec. 197(1) Cr.P.C, the prosecution sanction in the case of a Judge, Magistrate or Public Servant falling under situation 2 (a)(ii) or 2 (b)(ii) above shall be accorded by this Central Government. The Explanation to Sec. 197(1) Cr.P.C declares that no prosecution sanction will be necessary if a Public Servant is prosecuted for offences under Sections 166A, 166B, 354, 354A, 354B, 354C, 354D, 370, 375, 376, 376A, 376C, 376D or 509 of IPC.

E1(b) Who is the Sanctioning Authority under Section 197(1) Cr.P.C when the services of the employee have been lent ?

- If the services of the State Government servant have been lent to the Central Government and the accused public servant commits an offence while on such deputation, then it is the Central Government alone which can grant sanction to prosecute him. The question to be asked in this context is where is the public servant employed at the relevant time. If the offence is committed during his service under the borrowing Government, that Government alone is competent to grant prosecution sanction under Section 197(1) Cr.P.C. (vide R.R Chari v. state of U.P AIR 1962 SC 1573). But the position is different under Section 19(1) of the P.C. Act, 1988.

E1(c) Who is a Judge u/s 197(1) Cr.P.C ?

- Cr.P.C. Does not define the expression “Judge”, “Magistrate” or “Public Servant”. But in view of Section 2 (y) of Cr.P.C., the definition of expressions which are defined in the IPC can be taken as the definition of expressions which are not defined in the Cr.P.C. Section 19 of IPC defines the word “Judge” as follows:-

“19. “Judge” - The word “Judge” denotes not only every person who is officially designated as a Judge, but also every person, -

who is empowered by law to give, in any legal proceeding, civil or criminal, a definitive judgment, or a judgment which, if not appealed against, would be definitive, or a judgment which, if confirmed by some other authority, would be definitive, or

who is one of a body of persons, which body of persons is empowered by law to give such a judgment.

Illustrations

(a) A Collector exercising jurisdiction in a suit under Act 10 of 1859, is a Judge

(b) A Magistrate exercising jurisdiction in respect of a charge on which he has power to sentence to fine or imprisonment, with or without appeal, is a Judge.

(c) A member of a Panchayat which has power, under “Regulation VII, 1816, of the Madras Code, to try and determine suits, is a Judge.

(d) A Magistrate exercising jurisdiction in respect of a charge on which he has power only to commit for trial to another Court, is not a Judge.

E1(d) Who is a Magistrate u/s 197(1) Cr.P.C ?

- The word “Magistrate” is not defined both in the Cr.P.C. as well as the IPC. When both the Cr.P.C. and the IPC are silent regarding an expression, then naturally one has to have recourse to the General Clauses Act, 1897. Clause (32) of Section 3 of General Clauses Act defines a “Magistrate” as under:-

“ (32) “Magistrate” shall include every person exercising all or any of the powers of the Magistrate under the Code of Criminal Procedure for the time being in force”.

As per Section 3 (1)(a) of Cr.P.C any reference in the Cr.P.C without any qualifying words to a Magistrate in relation to a metropolitan area has to be construed as a Metropolitan Magistrate and in relation to an area outside a metropolitan area has to be construed as a Judicial Magistrate. This construction is to be resorted to unless the context otherwise requires.

E1(e) Who is the Sanctioning Authority U/Ss 197(2) and 197(3) Cr.P.C ?

- In the case of any member of the Armed Forces of the Union who is alleged to have committed an offence while acting or purporting to act in the discharge of his official duty, Section 197(2) Cr.P.C contains a ban on any Court taking cognizance of such offence without the previous sanction of the Central Government. Central Reserve Police Force falls within the expression “Armed Forces of the Union” under Section 197(2) Cr.P.C (vide Akhilesh Prasad v. U.T.Mizoram (1981) 2 SCC 150=AIR 1981 SC 806). Sanction to prosecute accorded by the appropriate Government under Section 132 Cr.P.C does not amount to sanction to take cognizance of offence under Section 197 Cr.P.C. (vide Ram Kumar v. State of Haryana (1987) 1 SCC 476= AIR 1987 SC 735).

- Section 197(3) Cr.P.C clothes the State Government with the power to direct that the provisions of Section 197(2) shall apply to such class or category of the members of the Forces charged with the maintenance of public order wherever they may be serving and thereupon the protection under Section 197(2) Cr.P.C will be available to such members of the Forces. But the previous sanction that will be required is that of the State Government and not of the Central Government. The expression “public order” in the context of Section 197(3) Cr.P.C should be understood in a wider sense so as to include “law and order” also unlike the narrow meaning attributed to the said expression in the context of preventive detention. (vide paras 9, 10, 12 and 13 of Rizwan Ahmed Javed Shaikh v. Jammal Patel (2001) 5 SCC 7 = AIR 2001 SC 2198).

- The real test to be applied to attract the applicability of Section 197 (3) is whether the act which is done by a public officer and is alleged to constitute an offence was done by the public officer whilst acting in his official capacity though what he did was neither his duty nor his right to do so as such public officer. The act complained of may be in exercise of the duty or in the absence of such duty or in dereliction of the duty. If the act complained of is done while acting as a public officer and in the course of the same transaction in which the official duty was performed or purported to be performed, the public officer would be protected (vide para 15 of Rizwan Ahmed Javed Shaikh v. Jammal Patel (2001)5 SCC 7=AIR 2001 SC 2198). The provisions of Section 197(2) Cr.P.C was held to be applicable to all members of the Delhi Police Force in view of the notification issued under Section 197(3) Cr.P.C(vide Balbir Singh v. D.N.Kadian (1986) 1 SCC 410 = AIR 1986 SC 345). See also Sarojini v. Prasannan 1996 (2) KLT 859 D.B; Sasi D. and Another v. State of Kerala and Another 2015 (5) KHC 215).

E1(f) Meaning of “acting or purporting to act in the discharge of his official duty” ?

This is a requirement of Section 197 Cr.P.C only and there is no such requirement under Section 19 of P.C. Act, 1988.

The intention behind Section 197 Cr.P.C is to prevent public servants from being unnecessarily harassed. The Section is not restricted only to cases of anything purported to be done in good faith, for a person who ostensibly acts in execution of his duty still purports so to act, although he may have a dishonest intention. Nor is it confined to cases where the act which constitutes the offence, is the official duty of the public servant concerned. Such an interpretation would involve a contradiction in terms, because an offence can never be an official duty. The offence should have been committed when an act is done in the execution of duty or when an act purports to be done in execution of duty. The test appears to be not that the offence is capable of being committed only by a public servant and not by anyone else, but that it is committed by a public servant in an act done or purporting to be done in the execution of duty. (Here, the Post Master General (PMG) was visiting a post office for inspection. A clerk working there requested him for cancelation of his transfer. Thereupon the PMG abused and kicked the clerk. Held that the alleged act was not in purported exercise of his duty since the act of abusing or kicking cannot be considered to be inextricably connected with in the performance of official duty, namely, inspection. It was accordingly held that for prosecuting the PMG for offences punishable under Sections 323 and 504 IPC, no prosecution sanction was necessary)

Where a person died on account of the beating by the police in a lathy charge to disburse a mob which indulged in clashes and rioting between two rival political parties on an election day, it was held by the majority in a 3 Judge Bench of the Apex Court that the act of beating by the police officer was during the performance of his official duty requiring sanction under Section 197 Cr.P.C (vide Sankaran Moitra v. Shadhana Das AIR 2006 SC 1599). The real test to be applied to attract the applicability of Section 197 (3) is whether the act which is done by a public officer and is alleged to constitute an offence was done by the public officer whilst acting in his official capacity though what he did was neither his duty nor his right to do so as such public officer. The act complained of may be in exercise of the duty or in the absence of such duty or in dereliction of the duty. If the act complained of is done while acting as a public officer and in the course of the same transaction in which the official duty was performed or purported to be perform, the public officer would be protected (vide para 15 of Rizwan Ahmed Javed Shaikh v. Jammal Patel (2001) 5 SCC 7=AIR 2001 SC 2198).

- The expression public order in Section 197 (3) Cr.P.C should be understood in the wider sense so as to include law and order also unlike the narrow meaning ascribed in the context of preventive detention. (vide paras 9, 10, 12 and 13 of Rizwan Ahmed Javed Shaikh v. Jammal Patel (2001) 5 SCC 7=AIR 2001 SC 2198). Thus, a Judge neither acts nor purports to act as a Judge in receiving a bribe, though the judgment he delivers may be such an act; nor does a Government medical officer act or purport to act as a public servant in picking the pocket of patient whom he is examining though the examination itself may be such an act. The test may well be whether the public servant if challenged can reasonably claim that what he does, he does by virtue of his office. (vide H.H.B. Gill v. The King AIR 1948 P.C 128; Albert West Meads v. The King AIR 1948 P.C 156; Ronald Wood Mathams v. State of W.B AIR 1954 SC 455=1954 Cr.L.J. 1161). The essential requirement is a reasonable nexus between the alleged act and official duty and it does not matter if the act exceeds what is strictly necessary for discharge of the duty (vide Abdul Wahab Ansri v.State of Bihar AIR 2000 SC 3187; State of H.P v. M.P. Gupta AIR 2004 SC 730; K. Kalimuthu v. State (2005) 4 SCC 512=AIR 2005 SC 2257; Jaya Singh v. K.K. Velayudhan (2006) 2 SCC 573=AIR 2006 SC 2407).

E1(g) Committing of certain offences cannot constitute acts done in performance of official duty

- In State of H.P. v. M.P Gupta (2004) 2 SCC 349 = AIR 2004 SC 730, it was held by the Apex Court that it was no part of the official duty of a public servant to commit offences punishable under Sections 467, 468 and 471 IPC and, therefore, there was no need for any sanction to prosecute such a public servant. Again it has been held that sanction for prosecuting a public servant for offences punishable under Section 409 and 468 IPC is not required since those offences cannot be committed in discharge of official duty. (Vide State of U.P. v. Paras Nath Singh (2009) 6 SCC 372-3 Judges ; Parkash Singh Badal v. State of Punjab (2007) 1 SCC 1; Bholu Ram v. State of Punjab (2008 ) 9 SCC 140). Following the decision in State of H.P v. M. P. Gupta (2004) 2 SCC 349, the Apex Court held that sanction under Section 197 Cr.P.C is not a condition precedent for the launching of prosecution for an offence under Section 409 IPC. (vide N. Bhargavan Pillai v. State of Kerala (2004) 13 SCC 217 = AIR 2004 SC 2317). In State of Kerala v. Padmanabhan Nair (1999) 5 SCC 690=AIR 1999 SC 2405, it was held by the Apex Court that it was no part of the duty of a public servant to enter into a criminal conspiracy for committing criminal breach of trust and as such it cannot be said that sanction under Section 197 Cr.P.C is a condition precedent for launching a prosecution for offences under Sections 406, 409 read with Section 120 B of IPC. Again in Harihar Prasad v. State of Bihar (1972) 3 SCC 89=1972 Cr.L.J. 707 the Supreme Court had held that it was no part of the official duty of a public servant to enter into a criminal conspiracy or to indulge in criminal misconduct and that the want of sanction under Section 197 Cr.P.C was, therefore, no bar to prosecute the public servant.

In R. Balakrishna Pillai v. State of Kerala (1995) 1 SCC 478 =AIR 1996 SC 901=1996(1) KLT 250 (Graphite case), it was held by the Apex Court that in the light of the peculiar facts of that case, the offence of criminal conspiracy punishable under Section 120 B of IPC alleged in that case was directly and reasonably connected with the official duty of the Minister for electricity attracting the protection under Section 197 (1) Cr.P.C. Accordingly, the accused ex Minister was acquitted of the offence under Section 120 B of IPC in view of the total absence of prosecution sanction under Section 197 (1) Cr.P.C which according to the Supreme Court had to be issued by the Governor.

Thus, in cases where it is no part of the official duty of the public servant to commit the aforementioned offences, then no prosecution sanction under section 197 Cr.P.C. is required to be obtained for prosecuting a public servant for the aforementioned offences whether or not such public servant is in service or out of service.

Note: Here the humble personal view of this author is different. It is only when a public servant exceeds his lawful authority and commits a criminal offence that the question of prosecuting him for that offence will arise and it is only for such prosecution that the sanction of the authority competent to grant sanction is required (vide Padmarajan C.V. v. Government of Kerala and Ors 2009 1 KLT Suppl. 1=ILR 2009 (1) Kerala 36 – para12).

The Supreme Court in Pukhraj v. State of Rajasthan (1973) 2 SCC 701 held that Section 197 Cr.P.C is not confined to cases where the act which constitutes the offence is the official duty of the public servant concerned because such an interpretation would involve a contradiction in terms since an offence can never be an official duty. The Apex Court was emphatic that an offence should have been committed when an act is done in the execution of duty or when an act is purported to be done in execution of duty .

I fail to see the logic or reason behind those verdicts which hold that certain criminal offences alone cannot be part of the official duty of a public servant. As if, the other offences were part of the official duty of a public servant !. In my humble view, a criminal offence punishable in law can never be considered as part of the official duty of a public servant. It is relevant to remember that insistence on sanction to prosecute a public servant does not mean extension of total immunity from prosecution. Very often, it is the righteous indignation of Judges which persuades them to search for and find out means to circumvent the statutory safeguards extended to certain class of offenders.

But the personal views of mortals like this author should definitely yield to the authority of binding judicial precedents, particularly of the Apex Court by the force of Article 141 of the Constitution of India.

F SEC. 19(1) OF P.C. ACT, 1988 DISSECTED AND DISMANTLED

- Sanction under Section 19(1) of the P.C. Act, 1988 to prosecute a public servant by the Central or State Governments or by the authority competent to remove the public servant from his office, is a condition precedent for the Special Judge to take cognizance of offences punishable under Sections 7, 10, 11, 13 and 15 of the P.C. Act, only if –

1 (a) he is employed in connection with the affairs of the Union.

AND

(b) he is removable from his office either-

(i) by the Central Government.

OR

(ii) with the sanction of the Central Government.

OR

2 (a) he is employed in connection with the affairs of a State.

AND

(b) he is removable from his office either-

(i) by the State Government.

OR

(ii) with the sanction of the State Government.

OR

3 (a) he is not employed in connection with the affairs of the Union or a State.

AND

(b) he is not removable from his office by or with the sanction of the Central or State Governments.

BUT

(c) there is an authority competent to remove him from office

Since 1 to 3 above do not use the words “ was at the time of commission of the alleged offence, employed”, prosecution sanction under Section 19(1) of the P.C. Act is not necessary if at the time of taking cognizance of the offence, the public servant has either retired from service or has ceased to be in office.

F1(a) Who is the Sanctioning Authority u/s 19(1) of P.C. Act, 1988

- In the case of situation 1 above the sanctioning authority is the Central Government. In the case of situation 2 above the sanctioning authority is the State Government. In the case of situation 3 above, the sanctioning authority is the authority competent to remove the public servant from office.

F1(b) Who is the Sanctioning Authority u/s 19(1) of P.C. Act when the services of the employee have been lent ?

- Since clauses (a) & (b) of Section 19(1) of the P.C. Act, 1988 envisage employment of a permanent character, those clauses are not attracted in the case of a State Government employee whose services have been temporarily lent to the Central Government on deputation. So, in a case where the offence is committed during the employee’s ad hoc service under the borrowing Government, it is clause (c) of Section 19(1) which applies since the authority competent to remove the public servants from office is not the borrowing Government but the loaning Government. Hence the State Government alone will be competent to grant prosecution sanction in such a case. (vide R.R. Chari v. State of U.P AIR 1962 SC 1573; Gurbachan Singh v. State AIR 1970 Delhi 102 = 1970 Cr.L.J. 674. But, as has already been seen under E1(b) above, the sanction to prosecute such an employee under Section 197(1) Cr.P.C will have to be accorded by the borrowing Government and not the lending Government.

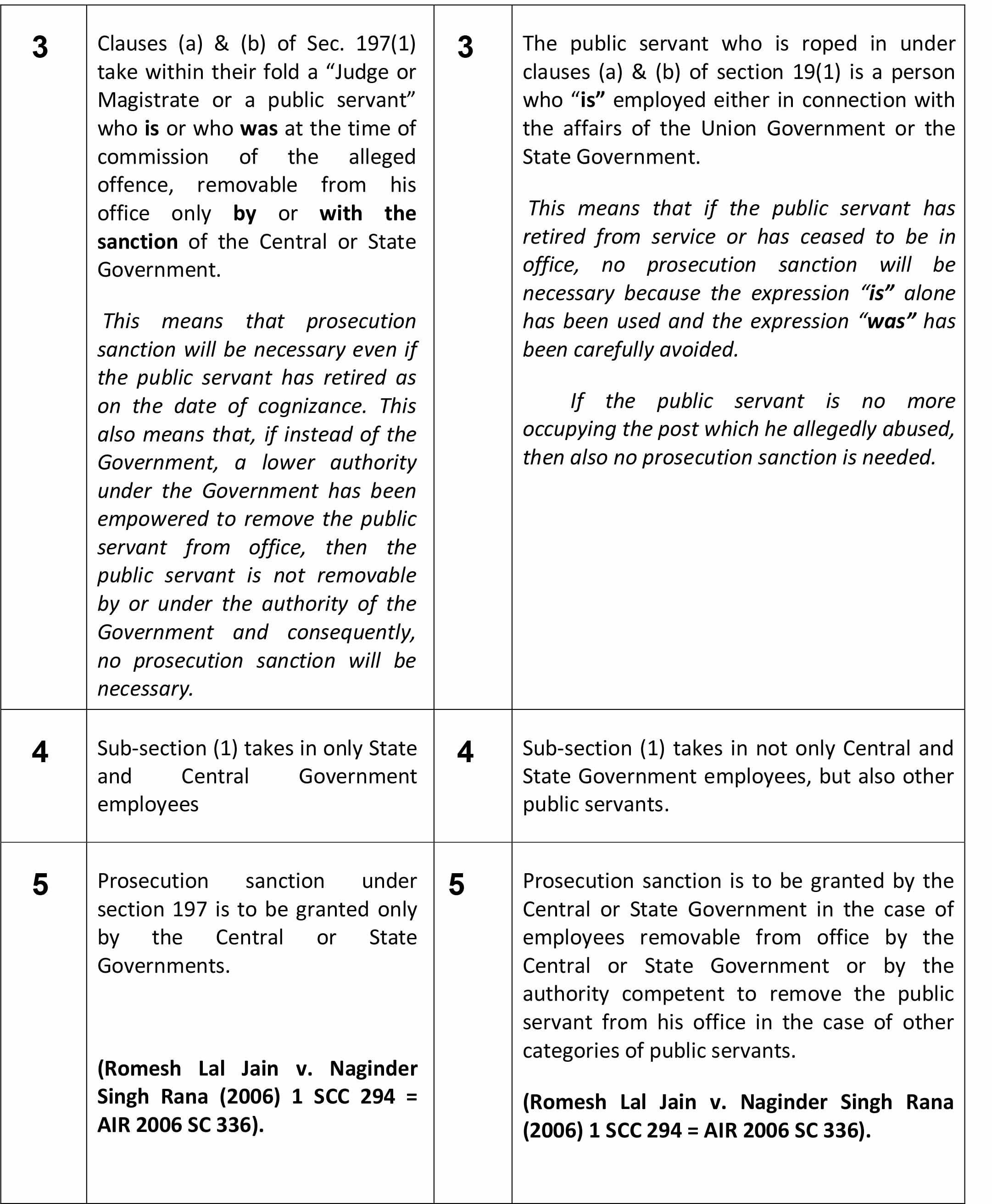

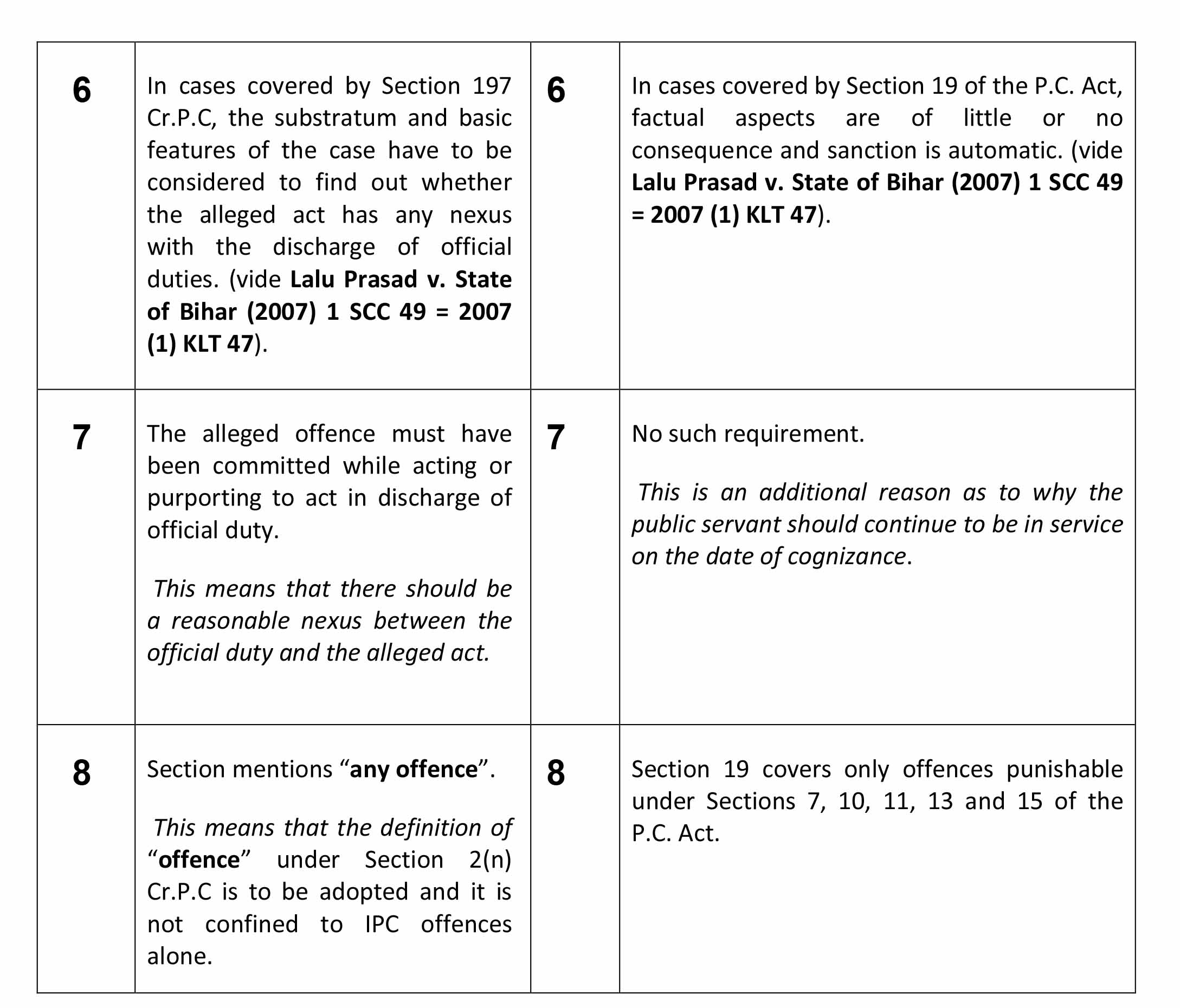

G DISTINCTION BETWEEN SECTIONS 197 Cr.P.C AND 19 OF P.C. ACT, 1988.

- The following comparative table shows the distinction between Sec. 197 Cr.P.C and Sec. 19 of P.C. Act, 1988.

H. NO SANCTION REQUIRED WHERE PUBLIC SERVANT HAS ALREADY RETIRED FROM OR CEASED TO OCCUPY THE POST

- The words “while acting or purporting to act in discharge of official duty” occurring in Section 197 Cr.P.C are conspicuously absent in Section 19 of P.C Act, 1988. Hence, prosecution sanction under Sec. 19 of the P.C. Act, 1988 is not necessary if by the time the Court is called upon to take cognizance of the offence, the accused public servant has already retired from service. (Kalicharan Mahapatra v. State of Orissa (1998) 6 SCC 411 = AIR 1998 SC 2595; State of Punjab v. Labh Singh (2014) 16 SCC 807; para 11 of S.K. Zutshi v. Bimal Debnath (2004) 8 SCC 31=AIR 2009 SC 4174; State of Orissa v. Ganesh Chandra Jew (2004) 8 SCC 40=AIR 2004 SC 2179; N. Bhargavan Pillai v. State of Kerala AIR 2004 SC 2317; State of H.P. v. M. P. Gupta (2004) 2 SCC 349=AIR 2004 SC 730; Rakesh Kumar Mishra v. State of Bihar (2006) 1 SCC 557=AIR 2006 SC 820). or has since demitted the office which he was occupying when the alleged corrupt act was committed. (vide Subramanian Swamy v. Manmohan Singh (2012) 3 SCC 64).

Sanction for prosecution of Ministers after resignation, for offences committed during tenure as Ministers, not required. (S.A. Venkataraman v. State - AIR 1958 SC 107 = 1958 Crl.L.J. 254; R.S. Naik v. Antulay (1984) 2 SCC 183 = AIR 1984 SC 684 - 5 Judges; K.Veeraswami v. Union of India - (1991) 3 SCC 655 - 5 Judges; Habibulla Khan v. State of Orissa - (1995) 2 SCC 437 = AIR 1995 SC 1124).

But in the case of an accused person facing prosecution for offences attracting Section 197 Cr.P.C, sanction is necessary even if the accused public servant has ceased to be a public servant on the date of cognizance in view of the user of the verb “was” in addition to “is” in Section 197 (1) Cr.P.C. (vide R. Balakrishna Pillai v. State of Kerala (1996) 1 SCC 478=AIR 1996 SC 901=1996 (1) KLT 250; Rakesh Kumar Mishra v. State of Bihar (2006) 1 SCC 557=AIR 2006 SC 820; Raghunath Anand Govilkar v. State of Maharashtra (2008) 11 SCC 289).

The Part I can be read here.Justice V.Ramkumar is a Former Judge, High Court of Kerala.

The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of LiveLaw and LiveLaw does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.