RBI Autonomy Is Neither A Myth Nor A Desire; It’s A Historical Fact

Chanakya Sharma

6 Nov 2018 11:13 AM IST

The Historical context of RBI reveals that its autonomy is not a myth. The central bank under the RBI Act, 1934 may not be as autonomous as US Federal Reserve System, yet it is far from being a mere governmental stooge.

The ongoing tussle between the Central Government & the Reserve Bank of India indicates the tumultuous times that we live in as also the institutional skepticism we are heading towards.

Ever since the news of government invoking (or initiating the process) Section-7 Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 broke, debates have started on whether the government is trying to sabotage the institutional independence of the RBI, or whether the interference under Section-7 is actually subterfuge to protect those closely linked with the party in power. Alternatively, others argue that the Reserve Bank of India, unlike its US counterpart, does not enjoy the absolute autonomy.

The basis for the allegation against the Central Government is not completely unfounded. A study conducted by Prof. Kunal Sen in 1996 found “a distinct increase in both the budget deficit and in its monetisation in the years leading to an election” while another found "a pattern of policy manipulation that points to election-year targeting of special interest groups possibly in return for campaign support, as opposed to populist spending sprees to sway the mass of voters.”

Easily blurred between these sharply divided positions is the vexed issue of law i.e. RBI autonomy and the extent to which the government interference is legally permissible.

Foundational Intent in RBI’s Conception;

The argument that the RBI does not inhere autonomy and has it only within the “framework of the Act” is an assertion that lacks perspective, both historically and factually.

In 1926, the Hilton &Young Commission recommended the setting up of an institution- the Reserve Bank of India - to be entrusted with pure central banking functions; essentially taking over the role of Central Bank which hitherto the Imperial Bank had been performing. The Imperial Bank was to be left free to do only commercial banking business. This transition was to take place as per the recommendations of the Hilton Young Commission in 1926.

The renowned economist John Maynard Keynes deposed before the Commission as following:

“I conceive a central bank as independent of the government in the sense...that it is an organ of the government on a level of authority with the Treasury.”

“The Bank, though ultimately dependent on the State, would lie altogether outside the ordinary Government machine; and its executive officers would be free, on the one hand, from the administrative interference of Government and free also, on the other hand, from too much pressure….where this might run counter to the general interest.”[1]

The Hilton Young Commission after analyzing submissions made by stakeholders observed :

“To eliminate the danger of political pressure being exercised upon the Boards of the Reserve Bank, it is desirable to introduce a provision in its charter directing that no person shall be appointed President….. if he is a member of the Governor-General’s Council, Legislative Assembly, or of any Provincial Governments or Legislative Councils.. “

“ Banks, and. especially Banks of Issue, should be free from political pressure, and should be conducted solely on lines of prudent finance.” –“In the spirit of these resolutions, care should be taken to assure….only a small minority of the Board shoxild be nominated by Government”.[2]

The Commission thus clearly observed a possible conflict of interest and envisaged a co-ordination based approach between the Reserve Bank and the Government on most functions and still grounded autonomy for the RBI for certain key roles. What then is the sphere of autonomy of the RBI, that government should not breach, at least in principle if not in law?

“Such a constitution will leave- the Reserve Bank free from interference from the Executive in the day to day conduct of itsbusiness and in banking policy, a condition which we consider of paramount importance.

“The Reserve Bank’ s principal function being to rediscount bankable bills held by the commercial banks, it is desirable that the Boards of the Reserve Bank should exercise their unfettered 'discretion in accepting1 or rejecting- such paper..”

The Commission clearly envisaged a structure in which certain crucial were to be beyond the pale of the executive government. Seen in this light, it becomes clear that even if the scheme of the RBI Act, 1934 is not based on absolute autonomy to the central bank, it nevertheless bases the foundation of the Reserve Bank on planks of specialization-based autonomy.

Power under Section-7 of the RBI, Act, 1934; Structured or Unfettered?

The draft Section-7 laid down by RBI before the central government was drafted after combining the provisions of Section 4(1) of the Bank of England Act, 1946, and Section-9 of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia Act, 1945.

Section-4 (1) of the Bank of England Act,1946 reads as follows:

“The Treasury may from time to time give such directions to the Bank as, after consultation with the Governor of the Bank, they think necessary in the public interest.”[3]

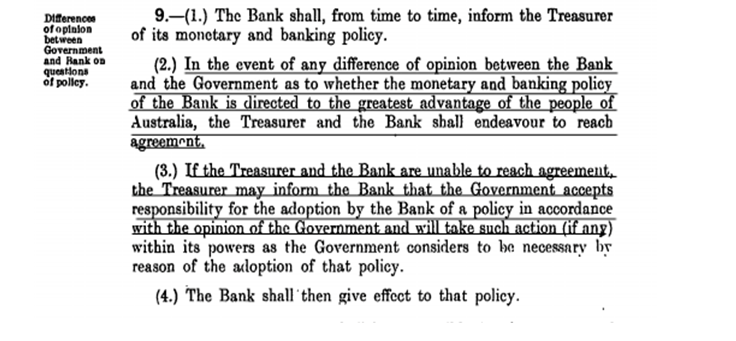

Section-9 (2) of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia Act, 1945

The document (History of RBI) notes that the Governor considered it desirable to make it clear in the Act itself that when the Government decided to act against the advice of the Governor, they took the responsibility for the action they wished to force on the Bank, like in the Australian model.

However, the government did not accede to this suggestion and removed the ‘responsibility’ clause from the Australian Act retaining, only the direction clause from the English Act.

Section-7 of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 thus reads as follows:

1)“The Central Government may from time to time give such directions to the Bank as it may, after consultation with the Governor of the Bank, consider necessary in the public interest”.2) “Subject to any such directions, the general superintendence and direction of the affairs and business of the Bank shall be entrusted to a Central Board of Directors which may exercise all powers and do all acts and things which may be exercised or done by the Bank.”

The two crucial phrase governing the dynamic between the Central Government and Reserve Bank under section-7(1) are; i) consultation with the Governer & ii) “necessary in public interest.”

The prior consultation with the Governor was to ensure that Government got the benefit of the Governor’s views on matters of importance to the country.

The burning issue that remains to be settled is as to what does the phrase “necessary in public interest”. In other words, can the government under fig leaf of ‘public interest’ thwart the foundational autonomy of RBI?

The issue of Section-7 first came up during an Allahabad High Court hearing on a case filed by Independent Power Producers challenging an RBI circular issued on 12 February.

The petitioners (Power-generation corporates) alleged that the circular violated fundamental rights completely ignoring the sectoral concerns of the power industry. The petitioners termed the RBI circular as ‘sector-agnostic’ as it did not contemplate the ground realities of different sectors and treated them alike. Standing Committee reports were cited to prove the problems of the power sector which required and individualistic approach.

On one hand the court had the RBI circular which laid down the policy clearly, while on another it had the public interest that would suffer if the power-corporations were to be held accountable. The court recognized the conflict and ordered the government to start consultative process under section-7, RBI Act,1934.

To the naked eye, it may appear to be an instance of court recognizing Centre’s power to fetter RBI’s autonomy & discretion. However, in reality the court has actually, and perhaps for the first time, recognized the limitations on center’s power to fetter RBI’s autonomy. The Chief Justice Dilip B. Bhosale observed:

“It is true that sub-section (1) of Section 7 of the RBI Act empowers the Central Government to issue directions from time to time to the RBI as it may, after consultation with the Governor, consider necessary in the public interest.

“The Central Government, however, is not expected to issue any directions, as contemplated under Section 7(1), indiscriminately or randomly. Such directions are possible when there exists sufficient material in support. I prima facie find that there exists material which deserves to be taken into consideration. The question, whether a breathing time deserves to be granted in the larger public interest and to achieve vision of power to all, needs to be answered by the Central Government.”[1]

This has two implications. Firstly, the consultative process cannot be ‘indiscriminative’ or ‘random’ as the court observes. Secondly, even after initiating the consultative process, the direction of the government must be based on some quantifiable data indicative of presence of public interest.

The court has therefore, while recognizing the Center’s power to use Section-7 has also in the same breath, remarkably so, grounded inherent limitations on the said power.

This theory is also in synch with the historical foundation of the RBI.

Reserve Bank of India; Autonomous Institution or Governmental Stooge?

The frosty relation between the central bank and the government has led many to reflect on the functional autonomy of RBI. So far there have been three instances where the government has hinted towards initiating section-7 consultations.

The first instance was when it did so in compliance of the Allahabad High Court judgment. The second was when the government on 10 October sought the governor’s views on using RBI’s capital reserves for providing liquidity.The third instance pertained to regulatory issues, including withdrawal of Prompt Corrective Action for public sector banks, easing constraints on banks for loans to small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

The Reserve Bank of India is invested with whole range of functions. Far from the assertion that it can be divested of its autonomy is the reality that there exists a sphere of functions that the government must not encroach upon, not without demonstrative evidence for sure.

The extent of Central Government’s power under Section-7 and other provisions of the RBI Act, 1934 is currently before a Constitution bench of the Supreme Court. The court will likely address these issues in greater detail. However, till such time as that happens, one may live with reasonable satisfaction that the apex bank of the country is not a governmental stooge, not in principle at least.

(The author is a final year law student at Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University)

[The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of LiveLaw and LiveLaw does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same]

[1] Independent Power Producers Association of India Vs. Union of India & 5 Ors.

[1] John Maynard Keynes, Deposition before Hilton Young Commission.

[2] Report of the Royal Commission on Indian Currency and Finance, I 926 (known as Hilton Young Commission) available at http://14.139.60.114:8080/jspui/bitstream/123456789/971/16/Royal Commission on Indian Finance and Currency, 1926 (325-457).pdf

[3] Section-4 (1), the Bank of England Act,1946 available at https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/9-10/27/section/4