- Home

- /

- Book Reviews

- /

- Book Review: Tackling...

Book Review: Tackling discrimination through Law

Review Editor

29 Feb 2016 3:08 PM IST

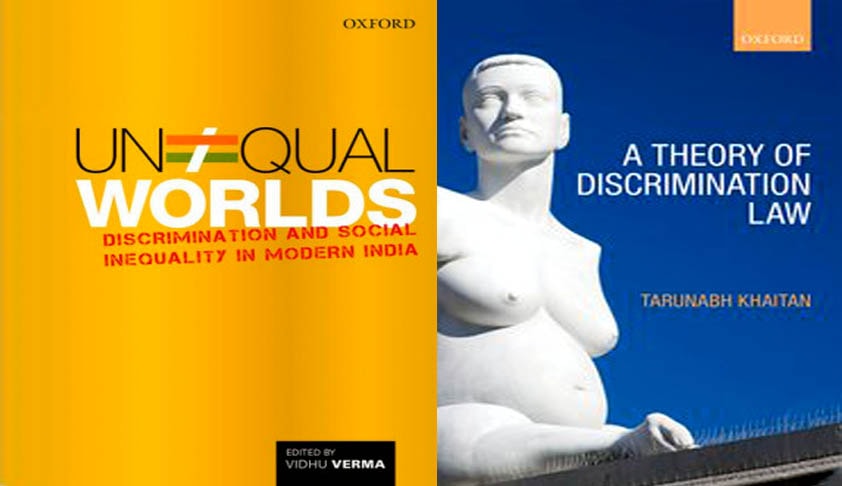

A THEORY OF DISCRIMINATION LAW BY TARUNABH KHAITAN, OUP, 2015, Rs.645, Pages 262.UNEQUAL WORLDS: DISCRIMINATION AND SOCIAL INEQUALITY IN MODERN INDIA. Edited by Vidhu Verma, OUP, 2015, Rs.995, Pages 422.Tarunabh Khaitan, who teaches law at Wadham College, University of Oxford, is a scholar known for his sensitivity to discrimination against and suffering by less privileged people in...

Next Story