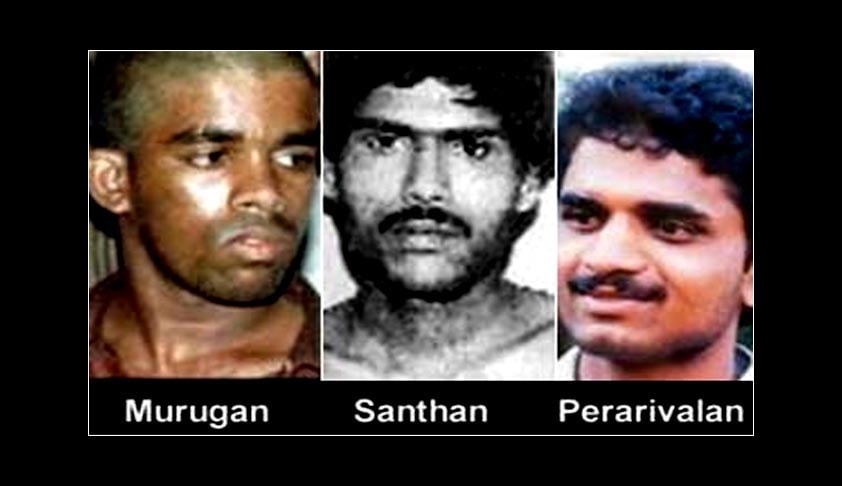

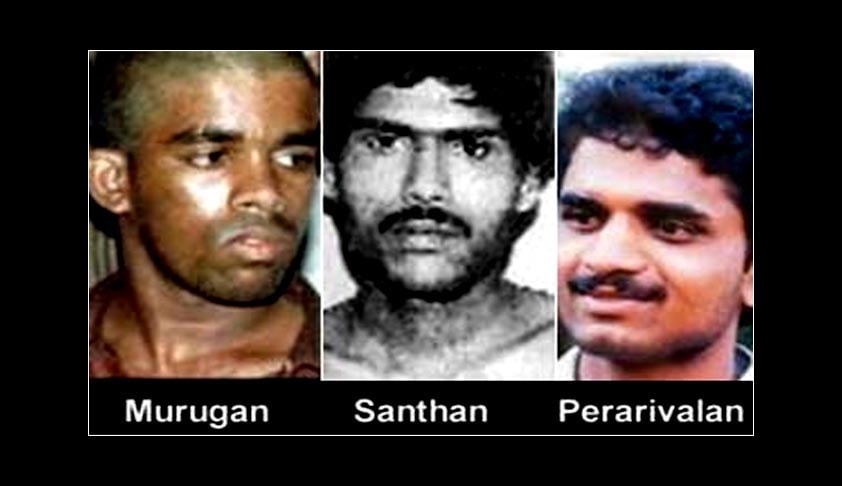

The letter sent by the Tamil Nadu Government’s Chief Secretary to the Secretary, Union Ministry of Home Affairs on 2 March seeking the latter’s views on the release of seven convicts in the Rajiv Gandhi assassination case is considered a political masterstroke by the Tamil Nadu chief minister, J Jayalalithaa on the eve of the state assembly elections.Analysts point out that there were...