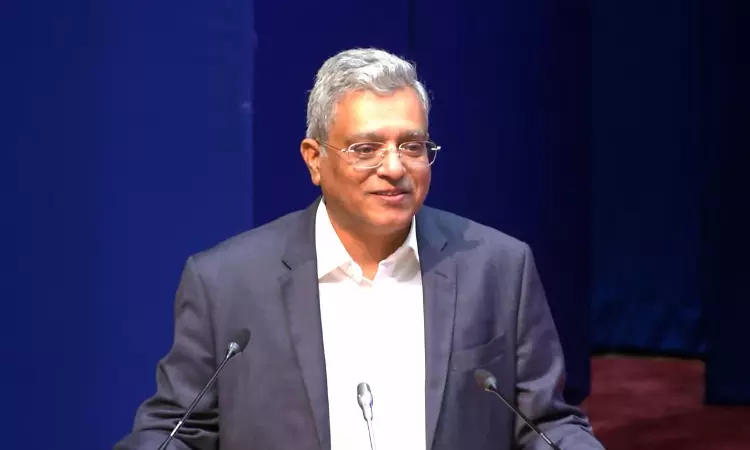

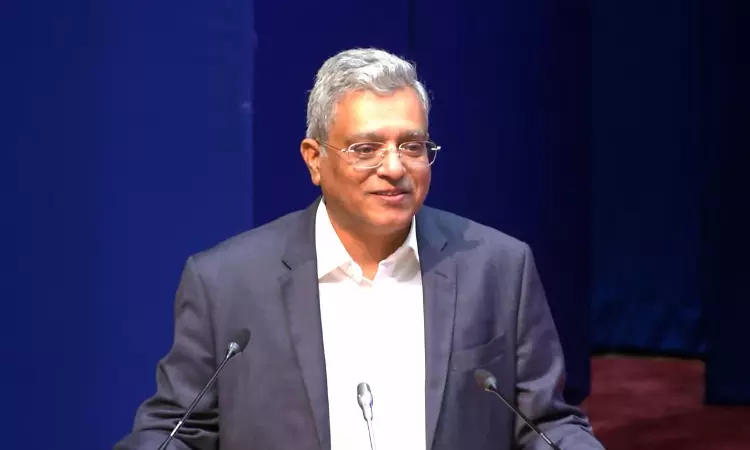

On the occasion of Vimukta Diwas, Justice P.S. Narasimha delivered a lecture on ‘Justice For Marginalised In A Constitutional Democracy’.Earlier, on August 30, Justice KV Vishwanathan delivered the keynote address on “Policing of Habitual Offenders: The Enduring Legacy of the Criminal Tribes Act in India” to commemorate the said ocassion. Justice Narasimha commenced his lecture by...