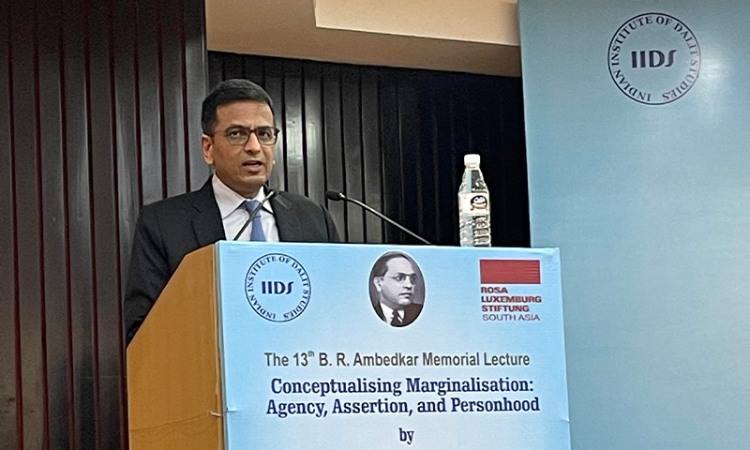

Narrow Concept Of 'Merit' Allows Upper Caste Individuals To Mask Their Obvious Caste Privilege : Justice Chandrachud

LIVELAW NEWS NETWORK

7 Dec 2021 10:15 AM IST

He said that while the professional achievements of upper caste individuals are enough to wash away their caste identity, this can never be true for the lower caste individuals.

Next Story