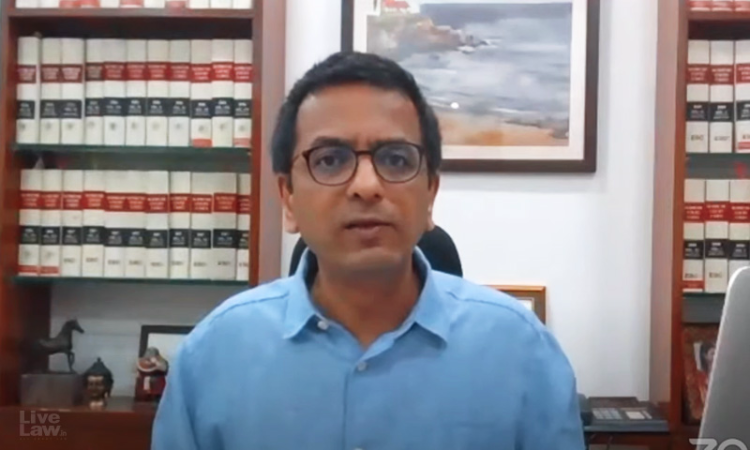

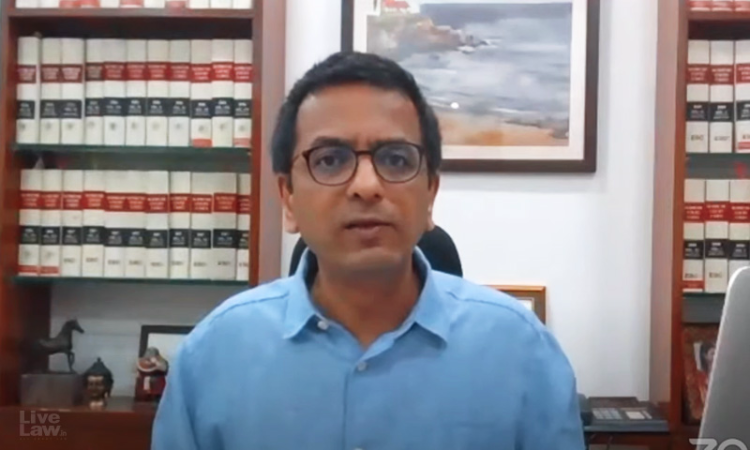

Mediation has the potential to be one of the avenues through which social justice can be achieved, observed Supreme Court judge Justice DY Chandrachud recently.But he added a caveat that the mediation setting should balance the social power, so that the weaker party is not forced into a settlement. Also, it should not promote a culture of impunity."Mediation has the potential to be one of...