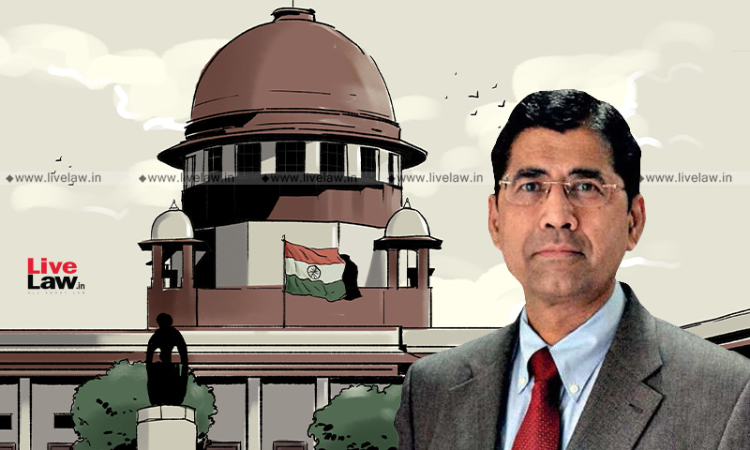

Tribunals Reforms Ordinance An Act of Legislatively Overruling Supreme Court Decision; Has To Be Struck Down : Arvind Datar

Mehal Jain

3 Jun 2021 12:24 PM IST

Next Story

3 Jun 2021 12:24 PM IST

The Supreme Court on Wednesday considered the contours of permissible and impermissible legislative overruling and if there is a power to legislate with retrospective effect to the result that judicial decisions stand overruled.The bench of Justices L. Nageswara Rao, Hemant Gupta and Ravindra Bhat was hearing the Madras Bar Association's challenge to the Tribunals Reforms (Rationalization...