Criminal Appeals And Setting The Muralidhar Standard Of Performance

Vaidehi Misra & Tarika Jain

10 March 2020 11:10 AM IST

Recently, the Supreme Court decided a criminal appeal where it found the accused not guilty of murder and acquitted him. In setting aside the Calcutta High Court's judgment, the Supreme Court held that the "circumstances relied by the prosecution to prove the guilt of the appellant were not complete". While this should have come as a huge relief to the accused, the fact that it came 36 years after he had first been convicted for murder, and a whopping 10 years after the appeal was filed in the Supreme Court, makes one reconsider the very use of the term 'relief'. Unfortunately, a case such as this is not an exception. Adjudication of criminal appeals in Indian courts is extremely slow despite the fact that they can be life defining for the parties involved.

Criminal appeals are a particularly complex case type which require in-depth appreciation of facts and evidence, and warrant focus and due application of mind. They are also of extremely high importance as they directly impact the verdict given by a lower court on the conviction or acquittal of an accused. For these reasons, judges may naturally be less inclined to hear criminal appeals and may prefer other case types which are relatively quicker to decide, such as bail applications or quashing petitions. It is thus no surprise that in 2018 (as per Vidhi's database), criminal appeals constituted the second highest category of cases pending in the Delhi High Court and had one of the lowest disposal rates. Even today, as per the NJDG data, criminal appeals constitute nearly 50 percent of the overall pendency in Delhi High Court.

Justice Muralidhar decided a significant number of criminal appeals: Study

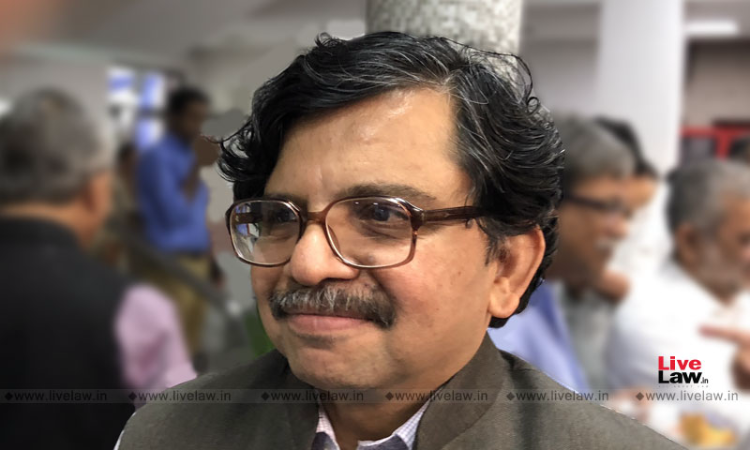

While much has been written about the events leading up to Justice Muralidhar's recent transfer, and his undoubted reputation as an impartial and a courageous judge ever since assuming office in 2006, not many know of this other impressive fact about him – Justice Muralidhar was one of the most efficient judges at Delhi High Court and more significantly, did not shy away from deciding criminal appeals.

In a study aimed at measuring the institutional performance of the Delhi High Court, for the time period between January 2018 and December 2018, Justice Muralidhar has emerged as a star performer for the institution, for various reasons including delivering deliberative justice. This study was done by extracting data from the Delhi High Court website and looking at the disposal trends for different judges.

In 2018, Justice Muralidhar headed a criminal division bench for approximately ten months, which heard criminal writ petitions, criminal appeals, death sentence references and criminal contempt petitions. For the remaining two months, he headed a civil division bench which heard income tax appeals, service matters, writ petitions pertaining to land acquisition as well as armed forces and company appeals. While the Chief Justice of the High Court is responsible for roster allocation of the judges, that is, broadly allocating the case types which are to be heard by a bench, the organisation of each judge's everyday causelist is completely their own prerogative and an indicator of how they prioritise cases and apportion their time. Unlike the other judges, especially those on the criminal side, Justice Muralidhar seemed to hear cases that require deeper deliberation, in particular criminal appeals.

During this time period, Justice Muralidhar delivered around 3917 'daily orders' (i.e. orders on the progress of a case mandatorily issued every time a case is listed on the causelist). Of these, a total 972 daily orders pertained to criminal appeals and references while another 506 pertained to criminal writ petitions. Generally, judges reserve judgements for complex cases that cannot be decided on the spot by an oral order as they require a substantial amount of judicial time. These judgments are then delivered at a later date by the Court. Justice Muralidhar pronounced a total of 175 judgments in 2018, a number considerably higher than the High Court's average. Moreover, out of these, approximately 127 were delivered in criminal appeals. This shows that Justice Muralidhar conclusively adjudicated on criminal appeals which not only require significant time and deliberation because of their complexity, but also need well-reasoned and detailed judgements by the court.

A stellar record for deciding complex criminal appeals

Even in the past, Justice Muralidhar has decided key criminal appeals, which exhibited clearly the independence of the judiciary as an institution and showcased rule of law as its top priority. One such was his sentencing of Sajjan Kumar to life imprisonment for criminal conspiracy during the Sikh massacre of 1984. Kumar was Congress leader and a Member of Parliament at the time of the massacre. A second significant criminal appeal decided by him pertained to the Hashimpura massacre of 1987. In his decision, Justice Muralidhar found the police guilty of targeted killing of Muslims, holding the state accountable.

Justice Muralidhar is a judge who is respected by all, the bar as well as the citizens, for his contribution to the justice system of the country. Undaunted by the challenge posed by criminal appeals, Justice Muralidhar strategically organized his roster to take the bull by its horns to deliver justice. His performance and legacy on the bench is a rare combination of efficiency and justice. It is for this reason that he shall be missed at the Delhi High Court and is being welcomed with open arms at the Punjab & Haryana High Court.

The authors are Research Fellows at the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, New Delhi and work on judicial reforms.