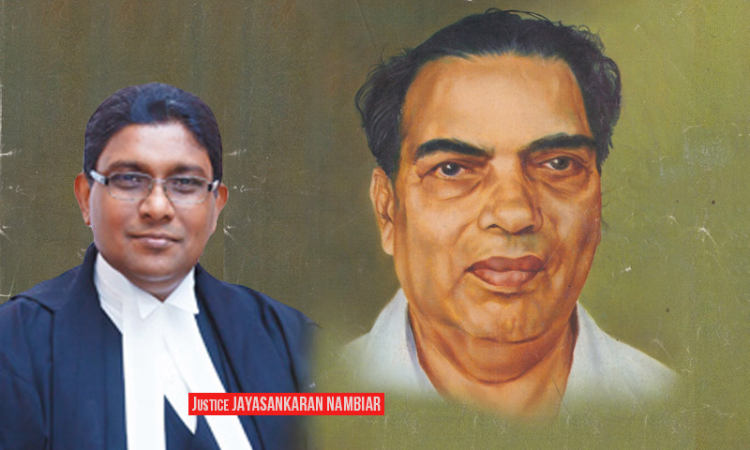

"Does The Ghost Of Gopalan Still Haunt Our Jurisprudence?" : A Search For The Contemporary Relevance Of A.K.Gopalan Vs State Of Madras

Justice Jayasankaran Nambiar A.K

28 Jun 2020 11:47 AM IST

For a landmark case that was decided in the first year of working our Constitution, I believe Gopalan does not get its due credit. I consider this rather unfortunate because a reading of the several opinions in Gopalan reveals the sheer erudition, judicial discipline and clarity of thought that guided the judges in the rendering of their respective verdicts, not to mention the fascinating, persuasive and riveting arguments advanced by the lawyers who appeared in the case. The opinions reveal an application of well established principles of interpretation of statutes as also the need felt by the judges to respect the doctrine of separation of powers indicated in the Constitution, thereby avoiding the temptation of legislating into the silences of the Constitution by gathering from an overall reading of it, a spirit and intendment that was never expressed in words.

The case itself concerned a challenge to a preventive detention law under which the petitioner was incarcerated. The main ground of challenge was that the incarceration infringed his fundamental right under Art. 19(1)(d) to move freely throughout the territory of India, more so when the restriction imposed on him did not satisfy the test under Art.19 (6) of being a reasonable one, that was necessitated in the interests of the general public.

The alternate contention raised was that if the effect of the law on him was to deprive him of his personal liberty then, in terms of Art.21, that could have been done only through a procedure established by law and this meant that it could only be under a law that conformed to the requirements of providing (i) notice (ii) an opportunity of hearing (iii) an impartial tribunal and (iv) orderly course of procedure. The term "Law" had to be taken as referring to valid law and the term "procedure" to certain definite rules of proceeding and not something that was a mere pretence for procedure.

Going further, and referring to the provisions of Art.22 of the Constitution, it was contended that the said Article was not a self contained code covering the law of preventive detention and that, in respect of matters not expressly provided for under Art.22, the requirements of substantive and procedural fairness had to be gathered from the other provisions of the Constitution. Some of the provisions of the statute were also impugned as infringing the fundamental right of the detenue to approach the Court under Art.32.

The majority view of five out of the six judges was that the allegation of infringement of a fundamental right had to be considered against the express provisions of the Article that guaranteed its protection. Thus, a challenge to a statutory provision as infringing the petitioner's right under Art.19 had to be examined in terms of the provisions of that Article and not any other provision of the Constitution. Viewed thus, what the incarceration had done was to deprive the petitioner of his personal liberty and not merely restrict his freedom of movement and hence, an examination of an infringement under Art.19 did not arise for consideration. Further, insofar as the petitioners incarceration had been through a procedure established under a law enacted by Parliament, the requirements of Art.21 were also seen as satisfied.

Noticing that during the debates of the Constituent assembly, the aspect of inclusion of a due process clause had been deliberated upon and it was decided not to include such a clause in Art.21, the court rejected the plea for reading in a substantive due process requirement into Art.21. It was observed that the court could not ignore the clear intention of the framers while interpreting the provisions of the Constitution.

The majority also found that Art.22 was a self-contained code governing the law of preventive detention in our country and that, it was not controlled by the provisions of either Art.19 or Art.21. Justice Mahajan observed that, when the constitution had taken away certain rights that ordinarily would have been possessed by a detained person, and in substitution thereof certain other rights were conferred on him even in the matter of procedure, the inference was clear that that the intention was to deprive such a person of the right of an elaborate procedure usually provided for in judicial proceedings.

Justice Mukherjea in his judgment went further and clarified that when there is a specific provision in the Constitution dealing with the subject of preventive detention (Art.22) then there is no necessity to read in a requirement of reasonableness of the law made under Art.22, especially when the said Article does not expressly say so. According to him, since all the provisions of the Constitution are to be given effect to, one cannot read in a requirement that is spelt out in Art.19, into Art.22 where it is not so contemplated. He then went on to explain the true scope and ambit of Arts.19 to 22 by observing that Art.19 gives a list of individual liberties and prescribes the restraints that may be placed upon them by law so that they may not conflict with public welfare or general morality. Arts. 20,21 and 22, on the other hand, are primarily concerned with penal enactments or other laws under which personal safety or liberty of persons could be taken away in the interests of society and they set down the limits within which the State control should be exercised. In other words, while Art.19 talks about freedoms, Arts.20, 21 and 22 deal with restrictions on state control. These restraints on State authority operate as guarantees of individual freedom and secure to the people the enjoyment of life and personal liberty, which are then declared to be inviolable except in the manner indicated in the said articles. Thus, while the freedoms in Art.19 may be connected with or dependent upon personal liberty they are not identical with it.

The only point on which the majority judges agreed with the petitioner was with regard to the contention that certain provisions of the impugned statute, that forbid the petitioner from disclosing the material communicated to him by the detaining authority before any court of law, had the effect of infringing his fundamental right under Art.32. The said provisions were therefore declared unconstitutional.

[JUSTICE A.K.JAYASANKARAN NAMBIAR]

The minority view of Justice Fazl Ali stands out in its acceptance of the contention that there is interplay of the rights guaranteed under Art.19, 20, 21 and 22. It was his view that while Art.22 contemplated certain procedural safeguards for the detenue under a preventive detention law, to the extent not expressed under the said Article, additional safeguards would have to be read in from Arts.19, 20 and 21. In his words, Art.22 does not exclude the operation of Arts. 19 and 21 and it must be read subject to those two articles in the same way as Arts. 19 and 21 must be read subject to Art.22. Art.22 must prevail in so far as there are specific provisions therein regarding preventive detention but where there are no such provisions in that Article the operation of Arts. 19 and 21 cannot be excluded. Art.22 is not a code in itself.

As for the interpretation of the phrase "procedure established by law", he agreed that the procedure in question had to be under a law that conformed to the requirements of providing (i) notice (ii) an opportunity of hearing (iii) an impartial tribunal and (iv) an orderly course of procedure. He thus read in a limited requirement of substantive due process into Art.21 of the Constitution.

The "Silo's theory" propounded in Gopalan, whereby one had to look to the particular Article that guaranteed the right alleged to have been infringed and test the validity of State action against the extent of delimitation of the right permitted under that Article, was based on an understanding that the protection of rights guaranteed under the Constitution was through control on state action. The said approach was consistent with American jurisprudence of the time where liberty to the citizens of that country was guaranteed through restrictions on State intrusion.

The Gopalan approach was followed in Kharak Singh Vs State of UP[1]. In that case, the petitioner was arrested in 1941 in a case of dacoity, but was later released for want of evidence. The police, however, compiled a history sheet against him that was essentially a personal record of a criminal under surveillance. The petitioner, who was subjected to regular surveillance, including "midnight knocks" moved the court for a declaration that his fundamental rights were violated. The challenge was repelled by the Court which maintained that the freedom to move freely throughout the territory of India, guaranteed by Art.19 (1) (d) was not infringed because the "midnight knocks" did not impede or prejudice his locomotion in any manner. The midnight knocks were found, however, to violate the petitioner's fundamental right under Art.21 since it amounted to an unauthorised intrusion into a person's home. The sanctity of the home and the protection against unauthorised intrusion was seen as an integral aspect of ordered liberty that formed part of "personal liberty" under Art.21.

The dissenting view of Subba Rao J in Kharak Singh however took a different line. It is in this judgment that one finds the seeds of the new approach to the interpretation of the scope of the protection of fundamental rights under our constitution. Subba Rao J recognised that there can be overlapping of the rights conferred by Part III and that the guarantee of fundamental rights was to be through protection of the rights in the hands of the individual. He accordingly held that where a law is challenged as infringing the right to freedom of movement under Art.19 (1) (d) and the liberty of the individual under Art.21, it must satisfy the tests laid down in Art.19 (2) as well as the requirements of Art.21. He also found that the midnight knocks violated the right to privacy of the petitioner, which was an ingredient of his personal liberty.

The majority view in Gopalan was, however, formally departed from only in RC Cooper & Ors vs UOI[2] where a 11 judge bench opined that under our Constitution, protection against impairment of the guarantee of fundamental rights is determined by the nature of the right, the interest of the aggrieved party and the degree of harm resulting from state action. Impairment of the right of the individual, and not the object of the state in taking the impugned action, is the measure of protection. It is the effect of the law and of the action upon the right that attracts the jurisdiction of the court to grant relief (The effects doctrine). On this line of reasoning, the court could hold that when a person approached the Court alleging infringement of his fundamental rights, the court could look into whether the state action was within the limits permitted by the Constitution and, in that process, whether the law that authorised the state action was one that was in consonance with the extent of protection guaranteed to the various fundamental rights under Part III of the Constitution. Thus, even if the deprivation of liberty was in accordance with a procedure established by a law validly enacted by the legislature, the effect of the deprivation on the individual had to be one that satisfied the test of a "reasonable" restriction of his guaranteed right. The effect of the deprivation had also to be fair to the individual in that it could not have been the result of an arbitrary exercise of power or discriminatory to the individual.

It was this view that was re-iterated by the Supreme Court in Maneka Gandhi Vs UOI[3] and is presently the one that guides our interpretation of Part III of the Constitution. The clear shift in approach becomes apparent when we read the judgment in a case that was factually similar to Kharak Singh, and involved the same issues, but was decided after Maneka Gandhi. In Gobind Vs State of MP[4], a case involving domiciliary visits by policemen who had opened a history sheet against the petitioner by treating him as a habitual offender, the Supreme Court, after considering the majority and minority views in Kharak Singh, chose to follow the latter and recognise a right to privacy as a right of an individual to a place of sanctuary where he can be free from societal control. It was observed that rights and freedoms of Citizens are set forth in the Constitution in order to guarantee that the individual, his personality and those things stamped with his personality, shall be free from official interference except where a reasonable basis for intrusion exists. After recognizing the right to privacy as a fundamental right, and striking down the impugned regulations as offending that right, it was acknowledged that the right would have to go through a process of case-by-case development and that the right should be subject to restriction on the basis of compelling public interest.

The question that is often asked today is "Has the approach in Gopalan been abandoned by our courts or does the ghost of Gopalan still haunt our constitutional jurisprudence?" It is my view that, while for the most part, the Gopalan view has been abandoned while considering protection of fundamental rights, for reasons that are not entirely clear we cant seem to let go of Gopalan when dealing with cases impugning preventive detention laws.

One would assume that, having steered away from the path of recognizing controls on state action as the means for protection of fundamental rights, and deciding to look at the effect of state action on the individual, to determine whether judicial intervention is required, the courts would look to the effect of the detention on the rights of the detenue to test the validity of the law authorizing the detention. After all, the majority view in Gopalan, that held Art.22 to be a self contained code on the subject of preventive detention law in our country, was premised on the finding that since Art.21 only required that the deprivation of personal liberty had to be through a procedure established by law and that there was no requirement that the law itself had to be a fair or reasonable one, the substantive and procedural safeguards against illegal detention, whether punitive or preventive, had to be separately provided through Art.22. Decided case law on preventive detention, however, shows otherwise. While deciding cases questioning the validity of preventive detention laws, there has been a strange adherence to the silos theory in that the validity of the law is tested only against the provisions of Art.22 of the Constitution, and the question asked is whether the state action was within the limits prescribed under the said article? The effect of the detention on the rights of the detenue under Arts. 14, 19 and 21 have seldom been considered. The decisions in Kartar Singh (1994) where the validity of the TADA Act was questioned and Dropdi Devi (2012) that involved a challenge to the validity of the COFEPOSA Act are cases on the point. The said state of affairs is truly disappointing. The transformative approach that was rung in through RC Cooper cannot exclude preventive detention laws from its scope. The same test of "effect of state action on the rights guaranteed to the individual" has to be applied even while testing the constitutional validity of a preventive detention law. What is sauce for the goose must also be sauce for the gander!

In present times, when it is well settled in our jurisprudence that the rights guaranteed under Art.21 cannot be suspended even during an emergency, can we afford to look askance when a detenue comes knocking on the doors of justice? Do we turn him away by assuring him that the State Executive, who is supposedly in possession of all relevant facts, including confidential information, knows what it is doing in the interests of the security of the State? Surely the answer to these questions must be in the negative. As sentinels on the qui vive, our courts must be vigilant to the inaction and excesses, of the legislature and the executive, so as to uphold the fundamental rights guaranteed under our Constitution.