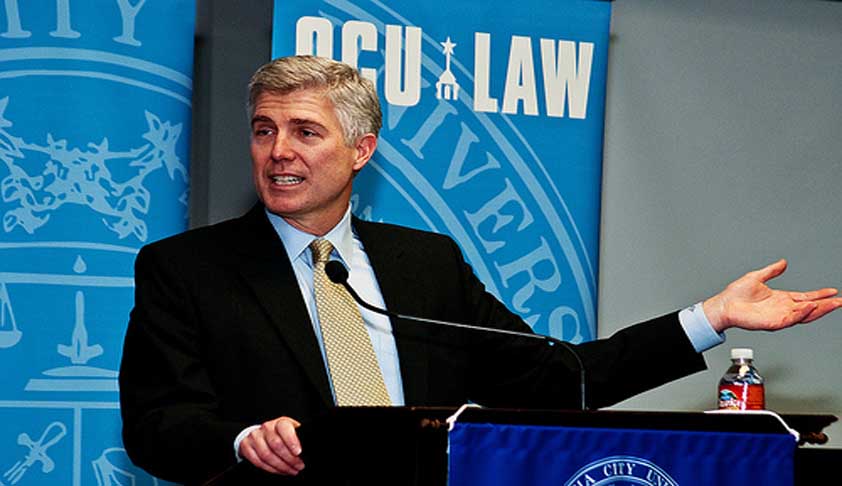

Conservative Judge Neil Gorsuch Nominated To SCOTUS By President Trump

Namit Saxena

1 Feb 2017 10:36 PM IST

Next Story

1 Feb 2017 10:36 PM IST

It has been reported that newly elected US President Donald Trump has nominated Neil Gorsuch, a federal appeals judge in Denver to the Supreme Court, filling the vacuum created by Late Justice Antonin Scalia who died in February last year. Neil Gorsuch, considered as an ardent textualist (like Scalia); is the son of the late Anne Gorsuch Burford, a Republican appointee of President...