Courts Are Closed But Is Justice On Leave? Revisiting The Debate On Judicial Vacations

Sneha Rao & Sohini Chowdhury

8 Nov 2021 7:25 PM IST

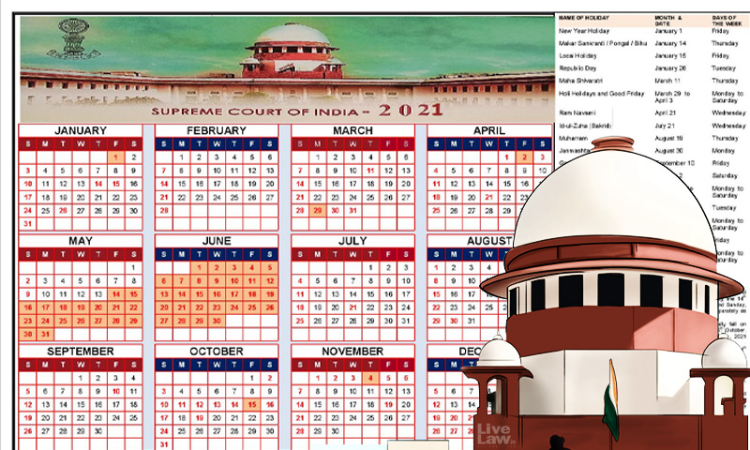

The 230th Law Commission Report had recommended that vacations in the higher judiciary be curtailed by at least 10 to 15 days and the court working hours be extended by at least half-an hour. The Justice Malimath Committee on reforms in the criminal justice system too recommended a 3-week increase in the annual working days of the Supreme Court to reduce the backlog of cases. The then Chief Justice of India, R.M.Lodha had also suggested that the Supreme Court cut down on its vacations. Partly as a result of all these suggestions, the Supreme Court Rules of 2013 were introduced in supersession of 1966 Rules cutting down the period of summer vacations from 10 weeks to 7 weeks. As per the Rules, the overall vacation period and court-mandated holidays are capped at 103 days a year, though these don't include Sundays and public holidays such as Holi or Diwali. Conventionally, the Supreme Court usually sits for 176-190 working days in a year (High Court 210 days and trial courts 245 days in a year).

While the word "vacation" might conjure an image of judges holidaying in exotic locations while lakhs of cases are pending in court, does the term "vacation" do justice to the idea behind having the courts being closed for a couple of months? What are the origins of the 'colonial practice' of taking summer and winter breaks? What work do judges do while on these 'vacations'? Is the correlation drawn between judicial pendency and vacations warranted and would cutting down on 'vacations' help address the issue of judicial pendency? Are there any alternatives to the current model of 'en-masse' vacations and would they be feasible?

In this background, LiveLaw talked to, Senior Advocate Anjana Prakash (former judge of Patna High Court), Advocate Dama Sesadri Naidu (former judge of Bombay, Kerala & AP High Courts); Mr. Bharat Chugh, advocate and former judge; Mr. Vikram Hegde, Advocate-on-Record, Supreme Court; Mr. Shrutanjaya Bhardwaj, advocate; Mr. Alok Prasanna, Co-founder and Lead, Vidhi Centre of Legal Policy, Karnataka and former judicial clerks to understand the idea behind courts going on vacation and the need for changes to this practice.

What are 'vacations'?

It appears that the origin story of these 'long vacations' dates back to the colonial times when the British judges had to make visits to their native land and the length of the holidays were designed keeping in view the long journeys that they had to make back and forth. Long summer vacations also have their genesis in the inability of the colonial rulers in coping up with the Indian summers - the judges sailed back to England to only return in the wake of monsoon. However, a response to an RTI application filed in 2013 and the order of Chief Information Commissioner (CIC) in subsequent appeal reveal that the Supreme Court does not have a record regarding the origin of the practice of its long summer vacations.

The idea of vacations also has its origins in the way the Supreme Court was envisaged to function as a special court. Vikram Hegde, a lawyer practising before the Supreme Court, sheds light on the link between the historical role of the Court and the practice of long vacations.

He explains:

"If we look far back enough, or even look at other countries, we will see that a superior court sitting to hear an issue was to be a special event. For example the US Supreme Court has only 39 days earmarked for hearing this whole year and 24 days for conferences. They have a long break of more than 3 months during which neither sitting nor conference takes place. Even the Supreme Court of India technically operates in terms. Hence there is a terminal list which is issued which mentions (in theory) all the cases that can be heard that term. Seen in this light, the vacation is not an exception but merely the gap between the sittings of court. Much like the gap between the sessions of parliament." But, he adds,

"practically the Supreme Court of India doesn't function like that anymore. It is no longer confined to only constitutional issues and the Special Leave Petition is not so special. Hence it is time to move away from a model which has its origins in either a summer so intolerable that our colonial masters couldn't bear it, or a sense that a sitting of a court is a special event."

Reflecting on the nature of work before our higher judiciary in its earlier days and the probable need for vacations, Senior Advocate Anjana Prakash, former judge of the Patna High Court explains: "In this context, one must keep in mind that earlier litigations were few, mainly of civil nature and each case was given a lot of time and energy thus leaving both the lawyers and Judges exhausted. Probably because of this, Judges and Senior lawyers would retreat during vacations to study and rejuvenate."

She is of the view that over time the "complexities of litigation have changed...Daksh Foundation had conducted a research on the quality of litigation in the Supreme Court and reported that about 70% of the cases were routine matters". Interestingly she points out that "...traditionally only junior counsels would appear during vacations before judges who did routine matters but once the Apex Court opened its doors to more routine matters even during vacations lawyers of all ranks appear before the vacation courts and the Court premises see the usual attendance of lawyers even though there are lesser number of Judges."

Seemingly, the practice of long summer and winter vacations has its origins in the way the higher judiciary functioned prior to Independence and the role envisaged for an institution like the Supreme Court. Based on these origins, it is argued that the 'colonial vestige' be done away with. However, the argument that judges don't need such long vacations rests on the assumption that during "vacations" judges take a complete break from their duties. What judges do on their 'vacations' is something that needs to be understood if one wants to understand the merit of the argument that vacations be cut short.

Alok Prasanna from the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy and Research, who has done extensive research on the issue of Judicial Reforms feels the argument that vacations be done away with stems from a basic misunderstanding of how the judiciary and the legal industry functions. He explains:

"Judges also work 16 hours a day. You speak to any judge you'll know that they effectively work 7 days a week. Especially High Court and Supreme Court judges. Because even their Sundays are spent travelling, fulfilling obligations as a judge- whether they are invited to speak at events or invited to inaugurate stuff, overseeing administrative work...It's not as if judges just enter the courtroom at 10:30 and leave at 4 and forget about everything. Judges either wake up early in the morning to read files for the day or stay up late in the night dictating judgment and passing orders...

"The invisible work that judges do is something people don't see. They still probably put in 80-90 hours a week. In that sense, it is absurd to say judges work only 165 days a year because that's how many days the court is functioning."

That the judges do a lot of 'invisible' work beyond strict court hours of 10:30-4 PM was also stressed upon by the Chief Justice of India N.V.Ramana. Speaking at an event, CJI Ramana had said:

"There exists a misconception in the minds of the people that Judges stay in big bungalows, work only 10 to 4 and enjoy their holidays. Such a narrative is untrue. It is not easy to prepare for more than 100 cases every week, listen to novel arguments, do independent research, and author judgments, while also dealing with the various administrative duties of a Judge, particularly of a senior judge….We continue to work even during the Court holidays, do research and author pending judgments. Therefore, when false narratives are created about the supposed easy life led by Judges, it is difficult to swallow."

Advocate Dama Seshadri Naidu, who was previously a judge at the Bombay High Court shares his experience: "..for a judge there is nothing like a holiday. Judges need to do a lot of research, perhaps at the Supreme Court level they have the semblance of assistance in the form of law clerks,etc..at the High Courts that isn't possible. So you need to do all the research and keep abreast with the changing trends in the judiciary and in the legal field. Judgeship is not a job to be done from 10-5 and just laze around during the weekends or the vacations. It's an intellectual exercise which requires round the clock effort on part of the judge."

A legal researcher-cum-judicial clerk who is currently working in the chambers of a Delhi High Court Judge shares her personal experience working in close quarters with a judge and opines that the term "vacation" is probably a misnomer. "A High Court judge in particular works on reserved judgements during vacations. These judgements require extensive research and drafting. On an average, at least on the criminal side, a Judge hears about 30-50 matters a day. So, during a working weekday, it's impossible for a Judge to devote time to writing judgements. That's where weekends and Court vacations come in. They allow the Judges to work on these reserved matters. Apart from the judicial work, there's also a lot of administrative work which needs to be done, and it's only during these days that they can be done, " she said.

Suniti Sampat, a former judicial clerk with Justice D.Y.Chandrachud reflect on her personal experience and shares that:

"This may vary across Chambers, but generally speaking, apart from working on reserved judicial orders and administrative tasks, judges have to read a heavy load of case files before Court re-opens. This is also because the first week of Court is typically a "miscellaneous week", during which Judges are required to hear an average of 50-60 cases every day of this week. "

Echoing the opinion, Shrutanjaya Bhardwaj, a lawyer practising before the Supreme Court adds: "Despite limited visibility into judges' lives, we know that they are so burdened that a significant part of these "holidays" are actually working days. This work is both judicial (like preparing for cases, researching and writing judgments, manning vacation benches etc.) and administrative (such as committee work). Figures and numbers will not capture this reality."

Bharat Chugh, shares his perspective of being a member of both the bar and bench and sheds light on the importance of these so-called 'vacations' and says:

"The judiciary does need vacations as judges/advocates are overburdened on a daily basis and work extremely long hours. Also the nature of work is such that a decision fatigue sets-in and it is important to unwind. Law is extremely exacting and strenuous as a subject; it takes a toll on a person both mentally and emotionally. This is true both for judges and advocates. In the absence of sufficient breaks, judges and advocates will suffer a burnout. Also, judges use these long breaks to write judgments that are pending and also catch up on research, which is essential for judges to maintain quality of justice. There is no doubt that judges work long hours."

He explains that 'vacations' are also important in light of the role expected of the Apex Court, he adds: "our Courts do not just hear constitutional matters; right up till the Supreme Court, judges hear even bail applications, injunctions, in addition to matters of constitutional importance. Our Courts, in that sense, discharge a much wider and exhaustive function. Further, on an average, High Court and trial court judges have 50-100 cases listed before them each day. This is a large number by any yardstick and more than their counterparts elsewhere in the Court. The time they spend in court is generally only a subset of their working time. Judges spend evenings, nights, and weekends reading files, writing orders, reading other judgments, and laws."

That the work of a judge, at any level of the Judiciary, extends beyond the time spent in courts - in undertaking research, passing orders, dictating judgments, fulfilling administrative duties and official engagements - is a fact that is lost on to people who have not observed the workings of the legal industry at close quarters.

Pointing out that during vacations, courts have vacation benches to deal with urgent matters, Senior Advocate Anjana Prakash states that: "To some extent the idea of the Courts being on vacation is indeed a misnomer because all Courts work even when there are a certain number of holidays. A part of the strength of Judges work, though for a reduced number of hours, to take up urgent matters. In Patna High Court a Single Judge according to its rules exercises all the powers of a Division Bench, thus the work goes on."

Under Rule 6 of Order II of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013, the Chief Justice of India has the power to constitute a special bench to hear urgent matters during the court vacations. The High Courts also constitute vacation benches as per their respective rules.

Therefore, the perspective that during 'vacations' courts, judges and justice is "on leave" is probably mistaken. It partly stems from the fact that the term "vacation" doesn't capture the work that the judiciary does beyond court hours and partly because the life of a judge, beyond court hours, is hidden from the general public.

Is the comparison with the Apex Courts of other countries warranted?

While making a case for cutting down on vacations, parallels are drawn with courts in other jurisdictions and other public institutions which do not enjoy such long vacations. Critics point out that no other public institution in India works only for 130-150 days in a year. The argument is partly untrue, as discussed above, because the higher judiciary is not really "on leave" and also because the working conditions of Indian Judiciary are starkly different from its counterparts across the world.

A study done by the Supreme Court Observer, undertaking a comparative analysis of the calendars of the apex courts of Australia, Bangladesh, India, Singapore, the UK and US, shows that while the Indian Supreme Court enjoys relatively long vacations, this preliminary finding is notoriously deceptive. The Supreme Court of India, hears oral arguments every week-day, throughout the year. By contrast, the apex courts of Australia, Singapore, and the United States only hear oral arguments during specified periods. While the Federal Court of the United States of America does not have as many holidays, (it remains completely shut for only 11 days for the year), however unlike the Supreme Court of India, it sits to hear arguments for an average of five to six days in a month. The rest of the days are kept for conferences, non-argument sessions, etc. The same is true for the High Court of Australia - though it sits to hear arguments only two weeks a month, the number of court holidays are considerably lower than that of our higher judiciary.

It seems like the difference arises in the terminology used to divide the sessions of Courts. While countries like Australia and USA count the days kept for attending conferences, non-argument sessions, etc. as working days, the Indian Calendar classifies every non-court day as a "vacation."

But comparisons are not to be made in the abstract, thinks Shrutanjaya Bhardwaj. He states "...The responsibilities and conditions of every office are different. For instance, Supreme Court judges usually work 7 days a week under intense workload. On Mondays and Fridays - when the Court hears fresh matters - every bench is required to hear around 50 cases. On a few occasions, upto 70-80 cases have also been listed on the same day. By contrast, the US Supreme Court hears 70-80 cases in the whole year."

As Advocate Naidu too points out "US 9 judges sit and decide, on an average, 70-90 in a given year. Every judge writes 10-15 judgments in 365 days whereas in India, a judge of the Supreme Court would be writing 10-15 judgments every day instead of the whole year. If you take the jurisdiction of Australia, they hardly sit till the end because they don't have much work and also because of speedy disposal of cases and not getting bogged down by procedure. So India should catch up on these fronts."

Another relevant consideration before making a comparison is the judge-to-population ratio and the size of the population of each of these countries-which translates into the workload that judges face. The judge-population ratio in India stood at 21.03 judges per million people in 2020, as was informed by Law Minister Kiren Rijiju. The Law Commission of India, in its 120th Report, had recommended that the strength of judges per million population should be increased to 50 judges per million population. In comparison, the United States of America has 107 judges per million people and the United Kingdom has 51 judges per million population.

Without keeping in mind the differences in the judge-to-populations ratios, caseloads, and the time spent hearing arguments, it makes little sense to draw a blanket comparison with other jurisdictions merely on the basis of official calendars.

The vacation structure of the higher judiciary has also been scrutinized in comparison to professionals from the medical community, enforcement agencies, civil servants, who are required to work round the clock without the luxury of long vacations. People in support of the judiciary taking much required vacations point out that the function of the judiciary is similar to that of Legislature. The Legislature works only in 3 sessions throughout the year yet nobody expects them to be in session 24x7 because people intuitively understand the duties of legislators extend to touring their constituencies, meeting their representative, etc. Likewise, it is pointed out, the duties of judges extend beyond court hours. However, detractors argue that the comparison between Legislature and Judiciary is slightly mistaken for "while the legislature does take long breaks, it does not have a daily transactional role like the judiciary."

Shrutanjaya Bhardwaj has an interesting perspective on this issue. He believes that decent vacations for judges are actually a good thing.

"We must not wish for overworked public office bearers—if there are other public offices which require work without leisure time, we should demand improvement in that sphere rather than trying to emulate that requirement in other spheres."

On the comparison with other professions, Alok Prasanna points out that "Teachers have 7-8 weeks off in summer and University professors also don't teach during these 'vacations' but they do administrative work. Likewise judges too don't work full strength during vacations but they don't go off to go chill somewhere. There are vacation benches, and other judges write their judgments,etc. They don't sit and hear cases but they are still working." Making a reference to studies which show a four day working week is actually leading to better productivity than a 5 day working week, he poses an interesting question, "I think it should prompt the opposite question. What jobs do you generally require to work 50 weeks a year? I can understand emergency public services requiring to work 50 weeks a year, but beyond that if you are an office junkie trying to sit in your office and trying to show loyalty to the boss by showing how long you are working everyday why is your way of working better way of working for the country or the nation?"

Further, he adds: "Keep in mind that most Supreme Court judges are working at an age when everyone else is retired...If you cut down on vacations you will only see people retiring earlier because they get burnt out by the time they turn 62."

Whether the collective work culture is becoming more toxic with each passing day with the boundaries between work and life eroding and people facing burnouts is an important issue. But that's a debate for another day.

Are cutting down on vacations the panacea to the issue of judicial pendency?

The biggest criticism that is leveled against the higher judiciary taking long vacations is the fact of thousands of pending cases. Critics argue that if we accept the proposition that justice delayed is justice denied, then the Supreme Court's vacations are simply unacceptable. The argument goes that if the higher judiciary just sat for longer periods of time then judicial pendency would go down. However, to accept that proposition one must first examine how much of a correlation exists between judicial vacations and judicial pendency.

The problem of judicial pendency is a vexed and complex issue. There are a host of reasons why year after year cases have been pending - judicial vacancies, repeated adjournments, among others. How much of a role do judicial vacations play in it?

Advocate D.S. Naidu feels that unless there is a comprehensive reform of the judiciary, cutting down 10-15 days of vacations will not solve the issue of judicial pendency. He adds that seeing vacations as the cause of judicial vacancies reflects a "knee jerk reaction of sorts" because cases are not pending on the grounds that judges are going on vacations. Explaining the primary problems ailing the judiciary, he says-

"There is inadequate infrastructural support for the judiciary. You know the international standard, for 10,000,00 people you need 50 judges and that's the acceptable norm and we have 18 to 20 per 10,00,000 people. So this inadequacy needs to be addressed by bringing in grassroots level change.

Everytime we try to improve our ranking in the Ease of Doing Business we introduce a slew of legislations- Fugitive Offenders Act, Commercial Courts Act- but have we ever seen new judge posts being created? We see new laws but we see the same old judges being assigned additional responsibilities. For example, take Family Courts. They have been taking care of everything under the sun and it takes a decade to have one matrimonial dispute settled. So we need to address the infrastructure inadequacies."

Second big issue contributing to the issue of judicial pendency, he feels, is because we have an enormous love for procedure. "Everybody thinks that without procedural niceties justice is buried. Procedure is there to ensure that decision-making is consistent and in fact the UK from where we adopted all these procedures have abandoned all these archaic, outdated methods…. in the agenda of importance, when it comes to reforms vacations is the last one, at best only symptomatic," he explains

Senior Advocate Anjana Prakash is unable to draw a strict correlation between pendency and vacations and she feels that there is a need for greater efficiency in the workings of the judicial system at every level. Indicating that the problem might be much deeper than just 'long vacations', she states - "We need to dispel the myth that we are doing some exalted work which requires a great deal of time and industry. As I pointed out earlier, most of our work is routine, and thus, I wonder whether the manner in which we deal with our cases has something to do with our subconscious desire to remain relevant. Do we feel it is our public duty to keep the public speculation and attention placing ourselves as a pivot? A reflected glory, so to say, which would vanish as soon as the work is accomplished. Maybe we are still clinging to the archaic mode of functioning because we have not learnt our democratic values well enough. We, therefore, willfully pass off procrastination as a ruse for abiding by the rule of law. All of us who are students of law have on numerous occasions been unable to fathom why a judge has chosen not to pass an order today that it will pass tomorrow. I would hate to believe it plays power games with the lawyers and litigants."

She goes on to state, "The recent example is the bail matter of an actor's son. My simple query is why did the matter come to the High Court when such an order could have been passed by the Special Court. Why was an ordinary routine bail matter heard for three days by the High Court at a stretch at the cost of so many other urgent matters."

Alok Prasanna also feels the correlation between vacations and judicial pendency, if any, is marginal. "The argument assumes that fewer days of courts functioning is the cause for delay. That's not true. It may contribute in some way, but there are many other reasons why there are delays in hearing...the Supreme Court did not have its full complement of judges until recently which contributed to cases piling up because you couldn't constitute enough benches. Second, the court allows all sorts of adjournments. Third, there is the problem that the Supreme Court prioritizes some kinds of cases over others. These are the tough questions we need to ask. I think vacations are an easy, pointless low-hanging fruit."

Going on, he adds -"We are still not dealing with the question of why the Supreme Court is dealing with 60,000 cases a year...Supreme Court issues notice in far too many matters which don't need to be heard...Why is it that people without resources cannot get their due in court? Why does the fast-track to justice exist for some?

"There are far, far more pressing problems than counting the number of days the court is sitting or not sitting. These are the issues we need to be talking about. Vacation is a tiny, trivial problem that doesn't really address any of the issues plaguing Indian judiciary."

That the debate surrounding judicial vacation only obfuscates the real issue of judicial pendency without addressing the systemic problems plaguing the higher judiciary is a sentiment shared by practicing advocates.

Shrutanjaya Bhardwaj, is of the view that discussions on the link between court vacations and pendency are misguided. "While I can see why that link has an intuitive appeal, delay in our justice system has more pressing causes which warrant criticism. These causes include judicial vacancies, repeated adjournments (for which both lawyers and judges are responsible), frivolous petitions, lack of time limits for oral arguments, judicial indiscipline in terms of following precedent, etc. Empirical research has shown that the Supreme Court's docket is hopelessly clogged with SLPs—the State being the most frequent litigant—even though Article 136 was meant to be an exceptional provision," he explains.

A report titled 'Towards an Efficient and Effective Supreme Court: Addressing Issues of Backlog and Regional Disparities in Access', published by Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy in 2016 indeed indicated that the Apex Court's 'exploding docket' is largely attributable to the overwhelming rate of admission of SLPs. As per the said report 67.44 % of the cases filed before the Supreme Court over the course of the year 2014 were SLPs.

A 2017 document published by the Department of Justice, Ministry of Law and Justice states that the Government, along with the Public Sector Undertakings and other autonomous bodies account for 46% of the total pending cases in courts. A recent study conducted by National Law School of India University, Bangalore also identifies the Government to be the biggest litigant. Denouncing the prodigal litigation practices of the State, Senior Advocate Anjana Prakash reckons "I am aware that there is a National Litigation Policy and on its lines States litigation policy has been formulated which is very holistic. Unfortunately for reasons best known to the respective Governments they are not followed. Therefore, it is time for the State to justify its stand in lines of its litigation policy especially because the state is the biggest litigant and huge amounts of public money is wasted on meaningless litigation."

Shrutanjaya Bhardwaj also points out that the argument for slashing vacations rests on the assumption that more working days mean more time to decide pending matters. It is forgotten that "more working days also mean more fresh cases—more trigger-happy PILs, more SLPs, more prolonged oral arguments in Court! Our efforts should be focussed on addressing the more systemic issues," he says. Alok Prasanna too shares the sentiment that more working days wouldn't do much for the cause of judicial pendency if the time isn't taken up to hear long-pending matters. "It doesn't matter if the Court sits for 30 more days if the 30 more days are going to be used by rich corporates to get their cases heard."

On the issue of finding solutions to the clogged up judiciary, Bharat Chugh adds,

"The answers to large pendency are not necessarily in curtailing vacations but in increasing the number of judges, equipping the trial court judges with law researchers (on the lines of HC/SC practice), or experiment with holidays in rotation. 'Holidays in rotation' instead of 'holidays en masse' can be a better approach to balance long working hours and vacations."

'En Masse' Vacations to 'Holidays in Rotation'

Acknowledging the fact that judges need time for research, reading and writing judgments, some people argue that the same cannot be at the cost of doing justice to the litigants. They suggest that there might be an urgent requirement to delve deeper into the function and structure of the judicial system to identify alternatives.

In 2014, the then Chief Justice of India, RM Lodha had proposed substituting en masse vacations with a system of judges individually availing vacation as per requirement. The proposal, however, did not entail any increase in the number of working days or working hours for the judges, it only meant the judges would go on vacation at different times of the year. The essence of the proposal being that the courts should not be kept shut for such a long period of time.

The proposal met with massive backlash from the bar - the State Bar Councils and the Bar Council of India countered the proposal with suggestions of courts functioning for longer hours and six days a week. In an interview with Scroll.in, the then President of the Supreme Court Bar Association had explained that "When a lawyer takes up a case, he needs to be prepared to be called for a hearing at anytime...If official vacation slots are scrapped, judges will still get their holidays, but lawyers will get no rest, because they could get called to court any time."

Can "holidays in rotation" (judges individually taking leave for research, writing, reading judgments instead of the whole court going on vacation) be explored as a substitute for the en masse vacations? And would it be feasible is another consideration?

While some lawyers feel there is no need to look for alternatives to the current model as the issue of judicial pendency can be addressed by focussing on more serious causes of delay, some others feel it's an interesting option which can be considered especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic which has led to rise in pendency of cases.

Vikram Hegde opines that "While I agree with those who say that the judges have a heavy workload and they deserve some rest, this can very well be achieved by one sixth of the judges going off for two weeks every three months in rotation and sit and write judgments, catch up on the law or whatever they want to. The other 83.4% can continue to hold court as usual at this time. This way the rhythm of court isn't disrupted and fewer cases will get pushed away into obscurity."

However, some other practitioners point out the practical difficulty that the suggestion of staggered vacations will run into. Explaining his apprehension at the suggestion, Alok Prasanna, adds: - "It might seem perfect in theory but will be completely unworkable in practice.The problem is there are only 15 benches. Imagine if the CJI has to plan benches around the planned vacations of 30 different colleagues. Imagine trying to constitute a 9 judge bench and not finding judges available together for a period of 4 weeks. It will be chaotic for the CJI to constitute benches. It is hard enough for judges and senior advocates to plan around their calendars at this time...and in the end what you will get is even further delays."

Utsav Saxena, advocate and a former judicial clerk at the Delhi High Court points at the need for "coordination" between the Bar and Bench. Most of the practicing lawyers take Holidays during the summer and the winter vacations and so, if in the "staggered vacations" model the Hon'ble Judges start going on leave in rotation it would be really tough for practicing lawyers to find mutually agreeable dates for hearings and holidays. The Delhi High Court too, while dismissing a PIL seeking 'vacations in rotation', had noted that "It is neither practically feasible nor advisable to work in rotation. It might become absolutely chaotic."

On the whole it seems that the idea of 'staggered holidays' might run into practical difficulties. However, given the unique situation posed by the COVID-19 pandemic where the courts have functioned in a manner where they have mostly heard urgent matters; and a large population of lawyers practicing before the district and trial courts was devoid of laptops/computers and the technological skills to participate in virtual court proceedings - adding on to the existing list of pending cases, the current model of 'en-masse' long vacations might need reconsideration.

While headlines like 'Why does the SC vacation so much?' and 'Does the SC need more vacations than your kid' make for tantalizing headlines, they might ignore the reality of the work undertaken by the judiciary during their so-called vacations and as interviewees have pointed out are a "lazy solution" to the real and systemic issues that plague the Indian Judiciary.As Advocate D.S.Naidu points out, in order to address the issue of judicial pendency the Supreme Court could perhaps consider restricting the admission process.

" A court like Apex Court where we have a handful of judges taking care of 130 crore people should consider not entertaining delay condonation applications, amendment applications-such things should not reach the Supreme Court. They should insist on matters of constitutional importance and matters which have a profound impact on people across the country. If you have such a self-imposed limitation, then you can have more time to deal with pending cases. For other high courts-vacancy filling up, creating more posts based on population and volume of cases, infrastructural support are the issues to be addressed. It is easy to say judges are going on vacations but these are the issues that need to be addressed. "

Another worthwhile suggestion to unclog the Apex Court has been to separate the functions of the Supreme Court as a Court of Appeal and a court to hear issues of Constitutional Importance. The Attorney General too had suggested the creation of four benches of Court Of Appeal with 15 Judges each sitting across the country to reduce the burden of the Supreme Court. Interestingly, in 2016 a Constitution Bench was constituted to consider this issue and despite 5 years having passed since no progress has taken place. That a Constitution Bench to consider a suggestion to unclog the Apex Court has been pending for at least half a decade is the stuff of irony.

It is nobody's case that the Indian judiciary which is beset with systemic issues resulting in inordinate judicial delays is not in need of urgent reform. However, these issues require serious deliberation from all stakeholders of the system. Blanket arguments seeking slashing of vacations ultimately do a disservice to the complexities of the issue of pendency of cases. Instead, measures like curbing frivolous filing of matters, increasing the strength of Indian Judiciary at all levels, filling vacancies, not stalling judicial appointments, scrupulously following Supreme Court's instruction to make e-filings mandatory in certain matters and, breaking away from the practice of unnecessary adjournments would go a long way in addressing the systemic issues plaguing Indian Judiciary.