The Ghost Of Supersession

Santosh Paul, Senior Advocate

18 Oct 2022 12:50 PM IST

It was the late 2000s. On the speaker's podium at the Indian Law Institute was Mr. Somnath Chatterjee, an eminent Parliamentarian and the then distinguished Speaker of the Lok Sabha. The subject, as it often was, an incident which impacted judicial independence. Sitting and waiting for their turn to speak were the aging but mentally agile Justice Krishna Iyer and the sprightly Soli Sorabjee. Krishna Iyer was engrossed in a book which he picked up lying on the table titled 'Judges' by David Pannick, then, made available in India. Chatterjee, suddenly, in the middle of his oration, made this jaw dropping statement "Nehru was told that the Chief Justice had to be given permission to attend an international conference and Nehru remarked 'Who was the Chief Justice?'". Krishna Iyer, jolted, dropped the book, and began focusing on the speaker.

This statement came as a revelation of sorts. The conflict between the judiciary and the executive headed by India's first Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru commenced almost immediately after the adoption of the Constitution. Legislatures were pushing land reform legislations which were being struck down by the courts as unconstitutional. The first shot was fired by the Patna High Court by striking down the Bihar Abolition of Zamindari Act 1948. This was the Bill drafted by Ambedkar, which President Rajendra Prasad was reluctant to sign, but did so on the opinion of Alladi Krishnaswamy Iyer.

Nehru's reaction, unlike most post-colonial leaders of his time, was seeking the constitutional route and not engaging in a war of attrition with the judiciary. This, was the genesis of the Constitution (First Amendment) Act 1951, which inserted Articles 31A and 31B to protect land reform legislations. Conflicts of this nature are inherent in constitutional democracies, and so it was in the case of India.

Then came the decision in State of West Bengal v. Bela Banerjee, where the Supreme Court mandated that compensation for land taken must be a 'just equivalent of what the owner has been deprived of'. In quick succession, the Supreme Court in Dwarakadas Shrinivas v. Sholapur Spinning and Weaving Co. Ltd. set aside the takeover of a mill without paying compensation for having violated the shareholders' fundamental rights. These decisions came in the midst of the first Five-Year Plan, as India struggled with competing claims over its meager total plan outlay of Rs. 2069 crores. Not deterred by the setbacks in the apex court, Pandit Nehru pushed for the Constitution (4thAmendment) Act 1955, which sought to amend Article 31 (2) by adding the words, 'no such laws shall be called in question in any Court on the ground that the compensation provided by that law was not adequate'.

This was followed by the striking down of the Kerala Agrarian Relations Act 1960, which was enacted to acquire Ryotwari land for redistribution among the landless. Nehru's solution, like always, was uncompromising and non-negotiable, that is, treading the constitutional path. Thus came about the Constitution (17th Amendment) Act 1964, which added 44 Acts to the Ninth Schedule, thereby making them immune from any challenge for violation of the fundamental rights.

The decisions of Golak Nath v. State of Punjab, R.C. Cooper v. Union of India (the Bank Nationalisation case) and Madhavrao Scindia v. Union of India (the Privy PursesJudgment) took the wind off the sails of reform legislations. They met with criticisms from as high a authority of the likes of M.C.Setalvad. For party loyalists they were subversive. Yet, Mrs. Indira Gandhi adopted the constitutional mechanism. Ten days after the Privy Purses judgment, Mrs. Gandhi dissolved the Parliament and called for the general elections. The Supreme Court's decisions were taken to the hustings - the Court of popular mandate. What followed was a thumping two-thirds majority, with her party securing 350 of the 518 seats in the Lok Sabha.

Supercession And Beyond

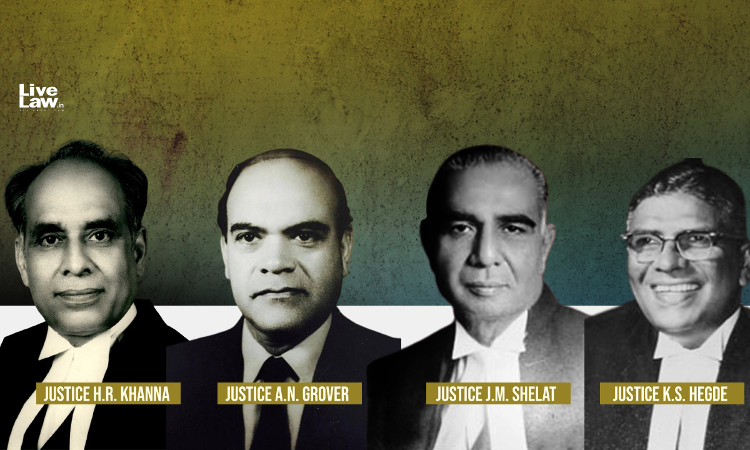

With the newfound overwhelming majority, Mrs. Gandhi ushered in the 24th and 25th Amendments to the Constitution. The Supreme Court in Kesavananda Bharati v.State of Kerala, with a majority of 7 judges, (6 judges dissenting), held that 'the power to amend does not include the power to alter the basic structure or framework of the Constitution so as to change its identity'. The very next day, on 25th April 1973, the President of India acting on the advice of the Cabinet superceded the three judges, Justices J.M. Shelat, K.S. Hegde and A.N. Grover who had written the majority opinion and stood in the line of succession for Chief Justiceship. Justice A.N. Ray was made the Chief Justice of India.

During the Emergency, the Supreme Court was once again tested in the ADM Jabalpur v. Shiv Kant Shukla (the Habeas Corpus) case. The majority agreed with the government's submission that fundamental rights stood abrogated during the period of the national Emergency. Justice H.R. Khanna was the lone dissenting judge held that Article 21 of the Constitution could not possibly be the sole repository of the fundamental right to life and liberty, as these rights predate the Constitution itself and cannot be subjugated to any executive decree even during the period of a national Emergency.

Nine months after delivering his famous dissent, Khanna J. was superceded to the office of the Chief Justice of India by Justice M. H. Beg.

In SCAORA I, (1993) the Supreme Court carried out a much needed constitutional course correction and held that "appointments to the office of Chief Justice of India have, by convention, been of the seniormost Judge of the Supreme Court considered fit to hold the office". The Court further held that a departure from the aforesaid convention is permissible only if there is a doubt as regards the fitness to hold the office. It was very clearly clarified there was "no reason to depart from the existing convention".

In due course three decisions of the Supreme Court— SCAORA I included, Special Reference Number 1 of 1998 and the NJAC judgement (2015)— endorsed the position that the baton of Chief Justiceship is to be passed on to the senior most puisne judge, unless there were compelling reasons to do otherwise.

It's been over four decades after the first supercession. Yet whenever the time comes for the change of baton, the fears are stoked of a supercession. The air in the social media rings out ominous scents. The online controversies add to conspiratorial speculation. This is the age of the trolls, where unverified and unverifiable data is thrown into the virtual space and allowed to spread at the speed of light. And unfortunately, the speed of disinformation outpaces the speed of a rational informed response.

The fact that this is happening, despite three judgments endorsing the manner, methodology and the larger purpose and spirit of how exactly this exercise has to be conducted, is an indication of the damage supercession did to our polity and our collective psyches.

All this could be avoided if the polity is geared to adopt the letter and spirit of that brilliant episode (9thDecember 1946 to 24th January 1950) in our history – the formulating of the text of our democratic constitutional republic. The shining lodestar was articulated by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru on 24th May, 1949 to the Constituent Assembly:

"Judges presumably in future will come very largely from the bar and it will be for you to consider at a later stage what rules to frame so that we can get the best material from the bar for the High Court Federal Court judges. It is important that these judges should be not only first-rate, but should be acknowledged to be first rate in the country, and of the highest integrity, if necessary, people who can stand up against the executive government, and whoever may come in their way…. High Court judges and Federal Court judges should be outside political affairs of this type and outside party tactics and all the rest, and if they are fit, they should certainly, I think, be allowed to carry on".

This perhaps gives an insight into the mind of India's first Prime Minister, who despite adverse decisions of the Supreme Court which nearly derailed land reforms, chose not to tinker with the judiciary. Granville Austin wrote on Nehru's response to anxious Chief Ministers who wanted a resolution on judicial stymieing of land reforms, "Nehru wrote to the Chief Ministers that the judiciary's role was unchallengable, 'but if the constitution itself comes in our way then surely it is time to change that Constitution'". It needs to be emphasized that it was the constitution not the judges which required a change. Nehru was fully aware of the tenuous nature of the experiment of constitutional democracy India had embarked on, and therefore, scrupulously chose not to tread on the independence of the judiciary. For otherwise, it would have had monumentally adverse consequences for the institution, and consequently, on democracy itself.

The author is a Senior Advocate in the Supreme Court and views are personal.