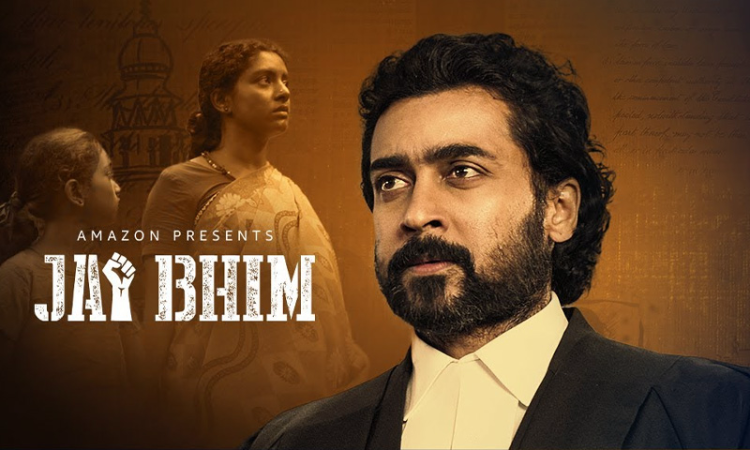

Law On Reels : 'Jai Bhim' - Court Room Drama With Impactful Portrayal Of State Impunity & Caste Violence

Shaileshwar Yadav

3 Nov 2021 1:38 PM IST

The Hindi film industry has for long romanticised the idea of police violence and unchecked power in the form of films like Singham and Dabangg. But Jai Bhim sets in motion the grim picture of custodial violence, police torture and misuse of the law by the police authorities. It somewhat breaks the narrative of idealising police brutality. Directed by T.J. Gnanavel, Jai Bhim investigates the intersectionality of caste fault lines and the State's authority. Mari Selvaraj's Karnan and Ashwin's Mandela are some examples that have gone to an extent to define caste hegemony persisting in the society. Jai Bhim, set in 1995, is a courtroom drama with a tribal woman and a protagonist who refuses to bow down to the arbitrary power of the State and could be seen knocking the doors of justice. The film is inspired from a case handled by Justice K Chandru, former Judge of Madras High Court, as a lawyer.

The story revolves around a tribal woman Senggeni from the Irula tribe and her deceased husband, Rajakannu – murdered in the custody of the police, following the false charges of robbery and an Ambedkarite advocate named Chandru. The film opens with a shocking scene. After being set free, the people of the Irula tribe are separated from other caste people, like wheat is separated from the chaff. Subsequently, they are picked up by various law agencies to reciprocate their hunger to solve cases by forging cases against Irula tribe people. Following which Advocate Chandru submits before the court about the exponential rise in arrest against a particular community in just ten days and wins the floor by getting an enquiry commission constituted. This act of state apathy marks the beginning of the grim portrayal of caste biasedness of the system.

Impunity and Custodial violence

Rajakannu, his family and friends (all of them belonging to the Irula tribe) got arrested by the local police in bleak anticipation of robbery. Further, what is witnessed is the cruel custodial torture for confession. The police here tried implicating Rajakannu of the robbery without any chance of being heard. Rajakannu had to face brutality, let alone any fair investigation. A few days down the line, Rajakannu, along with other arrested, went missing from the police station. Following which Advocate Chandru files for Habeas Corpus before the Madras High Court. It is worth noting that according to the National Campaign Against Torture, every day, on an average, five deaths have been recorded. The year 2019 alone recorded around 117 deaths in police custody while 1,606 deaths in judicial custody. These figures of custodial violence stand all-time high; the efforts taken to rectify it are dismaying; the conviction of perpetrators of such brutality is non-existent. The National Crimes Record Bureau's reports suggest that there has not been a single conviction in the case of 500 people who died due to alleged torture in police custody between 2005 and 2018. Though 58 police personnel were charge-sheeted, none of them faced conviction.

Another report by the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) recorded 1,723 cases of death in custody. NHRC report added that most of these deaths were the result of police torture. Further, the victims of these institutionalised crimes have something in common, they all come from marginalised backgrounds. Out of 125 deaths in police custody, 75 deceased (60 per cent) were from marginalised communities, 13 were Dalits or from tribal communities, and 15 were Muslims picked up for petty crimes. In a recent case, Arun Valmiki, a Dalit sanitation worker, allegedly died in police custody. Arun's family members have recalled that "he was beaten up mercilessly in front of his wife". The government in the Lok Sabha noted that around 1,189 people faced torture, and 348 people died in police custody in the last three years, jarring as it seems. Now I leave the question of deciding the nexus between reality and the cinematic exposure of custodial violence upon the readers.

Caste, Oppression and law

Jai Bhim has not limited its canvas to just custodial violence. it also categorically questions the intent of the State and victimisation of marginalised communities. While Dr. Ambedkar's ideas have been a bulwark in asserting social justice and fostering a just society – the institutions have entirely forgotten his vision and principles. Ambedkar's words that "however good a Constitution may be, it is sure to turn out bad because those who are called to work it, happen to be a bad lot.." finds quintessential relevance here. The State's failure to protect the fundamental rights of the marginalised cannot be seen as a failure of the Constitution but of the people sitting at the helm.

Further institutionalised caste hierarchy is deeply embedded in the system, remains the central pole of discriminating policies. "Drunk On Power", a report by the Criminal Justice and Police Accountability Project, talks about the victimisation of 'Vimukta' communities using the Excise Act, precisely law as a weapon of oppression. Vimukta communities continue to be regarded as 'hereditary criminals'. They are disproportionately accused, surveilled and kept under regulation by local law enforcement. Similarly, in the film, many instances could be witnessed where the Advocate General and the police officers contented casually that the Irula tribes are hereditary criminals.

Dignity and assertion of rights

Though there are laws to protect the interests of disadvantaged groups, the real question is how far they are realised and asserted against institutional discrimination? The film also captures scenes of higher police officials offering Senggeni money as compensation to neutralise the case. However, Senggeni's reply that she would rather lose the fight (case) but would not live on the alms of her husband's murders is subtle and dignified. It is the realisation that the fringes of caste and class do not circumscribe dignity – it cannot be decided on the whim and fancy of the oppressor, and what's paramount is that it cannot be compensated. Senggeni's quest for justice is an exemplification of constitutional principles. However, it comes along with a stretched struggle with Advocate Chandru's heroism. However, I somehow find this rare 'heroism' by a lawyer problematic – not what Chandru does. But on a different tangent, my questions would only be – can a system be allowed to make people this vulnerable? Has every Senggeni found a rare hero? Why does this system force people to go through what Senggeni has gone through? All of these questions need introspection without any prejudice.

Before parting, it has to be mentioned that the movie stands out. Beyond the debate of ratings, it must be watched time and again. It gives a lesson for everyone – State agencies, lawyers and law students- a long-forgotten responsibility that everyone is embodied with to uphold the Constitution. Brick by brick, a better society could be constructed. At last, Jai Bhim (an Ambedkarite slogan) brings a ray of hope. Succinctly, a Marathi poem puts it as – Jai Bhim means light… love… journey from darkness to light… tears of billions of people.

(The author can be reached at @shaileshwar21)