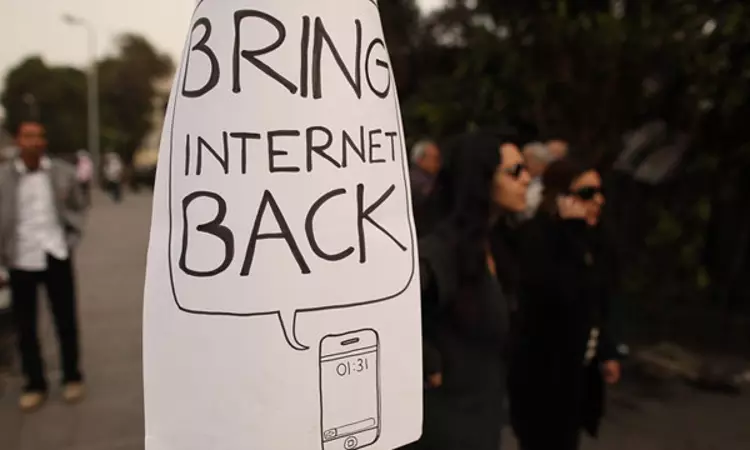

In Kashmir, for the last 47 days, 1.25 crore people have been deprived of their Right to Information encompassed under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India, and the pin-drop silence in the halls of the Supreme Court is virtually its acquiescence of the abrogation of this Fundamental Right. The communication lockdown; a complete divorce from the "outside world"; lack of access to the internet; these are all impositions by the State that are tearing down the walls of our Fundamental Rights, whilst the Supreme Court watches its disintegration as a bystander.

In this context, the Kerala High Court's judgement in

Faheema Shirin R.K. v. State of Kerala on 19.09.2019, upholding the Right to Access Internet as a part and parcel of Right to Privacy and Right to Education has come at an opportune moment. Justice P.V. Asha not only acknowledges the pervasive impact of internet connectivity in this day and age, but also the foundation it has formed in a person's ability to function with dignity and freedom. The Judgement also notes the Resolution dated 14.07.2014, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, which stipulates the importance of accessibility to the internet and the State's duty to uphold the unhindered right of its citizens to the same. The sole caveat that exists is the fact that a Single Judge of a High Court barely has any persuasive value on the mindset of the Supreme Court of India.

'Right To Access Internet Is Part Of Right To Privacy And Right To Education' : Kerala HC [Read Judgment]

The "Right to Know" was first elaborated in the case of Reliance Petrochemicals Ltd. v. Proprietors of Indian Express Newspapers, Bombay Pvt. Ltd. (1988). This case enshrined the fact that in order for a democracy to function effectively, its people had the right to know and obtain information regarding the conduct of the State. In S. Rengarajan & Ors v. P. Jagjivan Ram (1989), it was held that freedom of expression cannot be suppressed on account of threat of demonstration and processions or threats of violence which would tantamount to negation of the rule of law and the surrender to blackmail and intimidation. In Secretary, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting v. Cricket Association of Bengal (1995), it was held that it was the fundamental right of every citizen to impart as well as receive information through "electronic media", which could very well be extended to the "internet".

In 2015, the United Nations had officially declared internet access as a human right, calling upon all its member states to implement the same. It was in the case of

Sabu Mathew George v. Union ofIndia and Ors. (2018) that the Supreme Court declared that the Right to Access Internet is a basic fundamental right, which could not be curtailed at any cost, except for when it "encroaches into the boundary of illegality." They observed that the "right to freedom of speech and expression" subsumed the "right to be informed" and "the right to know". The Internet offered a "feeling of protection of expansive connectivity"; therefore, a citizen's right to right to seek and gain information, knowledge and wisdom was the obvious corollary to their Right to Access the Internet.

In the book, "Offend, Shock and Disturb" by Gautam Bhatia, the author states that there has been a transformation in the traditional sites of public discourse.

"Parks, towns, public streets – are now complemented by their digital equivalents: Twitter, Facebook, and the like." Therefore, a clampdown on internet services is technically a method of muzzling any form of debate and discussion that can crop up. While the traditional sites have been done away vide the imposition of Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, the unconventional sites of public discourse have also been smothered with an unconstitutional lockdown by widening of the Section. The Supreme Court's categorical dismissal of the gravity of the situation and a casual outlook of the same is a downright betrayal of the faith imposed in it as the

sentinel on qui vive.

In this regard, the Kerala High Court's judgement is a compelling nudge to the Apex Court and a reminder of its decision

in the

K.S. Puttuswamy v. Union ofIndia (2017), upholding the Right to Privacy. It is hard for the common man to grasp the fact that the very Court which had delivered a judgment such as the one in the

Puttuswamy Case in 2017, has now been rendered incapable of undoing prima facie injustice being inflicted on a significant section of the society. An argument that had been propagated by the Petitioners in the Aadhaar case was that the Constitution of India did not enumerate the powers of the State, but was a manifesto stipulating the restrictions/limits on the actions of a State. Additionally, there had been

"an inversion of the accountability in the Right to Information age". The burden of proof had shifted from the State to the citizens; the latter being subjected to its curtailment of Fundamental Rights under the garb of "national interest". One can note that this is not just applicable to Kashmir, but has been discernibly evoked in other recently promulgated statutes as well, for instance, the State's unbridled right to denounce a person as a terrorist under UAPA.

One can remember that the

K.S. Puttuswamy judgement had

ushered in a new beginning for Constitutional jurisprudence. While Right to Privacy had been passably enumerated in certain cases in the pre-Puttuswamy era (i.e.

R. Rajagopal v. Union of India in 1994), the unanimous decision of the 9-judge bench, enshrining the importance of the Right to Privacy and its all-encompassing features, opened up new avenues for all subversive entities. In addition to the above, the Apex Court acknowledged the exponentially high rate of change and development in technology, and called in question the necessity to include these facets in the Right to Privacy, thereby accentuating the transformative nature of the Constitution. In the judgement, Dr. Justice D.Y. Chandrachud invoked French philosopher Michel Foucault's "knowledge is power" adage and linked it to the all-pervasiveness of the internet. He propounded the importance of the internet for the conduct of the day-to-day life of a person and elaborated the power one possessed if one was informed. In the same vein, Justice S.K. Kaul warned us of the State's use of internet as a tool to control the

"expression of dissent and difference of opinion, which no democracy can afford." While the same was highlighted in the context of State control of data, a complete blackout of access to the internet can be stretched and brought into the same bracket.

Not just in India, foreign jurisprudence has also placed Right to Privacy on an enviable pedestal. The Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution, for instance, protects the citizens' right to privacy and protects it from the State's unreasonable intrusions. In the United Kingdom, Article 8 of the Human Rights Act protects privacy, family life, home and communications. This entails respect for the right to uninterrupted and uncensored communication with others. Consequently, in the case of

10 Human Rights Organisations v. United Kingdom, the European Court of Human Rights in 2018 ruled that the UK government's mass interception program violated the rights to privacy and freedom of expression. The interference was stated to be disproportionate to what was "necessary in a democratic society".

Uninterrupted access to the Internet, therefore, has become an indispensable tool in the exercise of democratic participation. 'The Next Billion Online' research conducted by Booking Holding in China, India and Indonesia emphasizes the

"rapid growth of Internet use and the clear link between connectivity and opportunity; people have stopped regarding the Internet as a luxury and come instead to regard it as basic human right." 74% of the people surveyed in India agreed to Internet access being a basic necessity; a fundamental right; and the need for equal access to internet connectivity. By cutting off a major section of the society from this right, the State has invariably destroyed their right to participate in a democracy. The implementation/imposition of this State-sanctioned lockdown in Kashmir is no less than a mockery of the tagline "world's biggest democracy", and a remnant of a dictatorial system of government wherein debates and dissent are stifled in the name of "national interest".

When the very section of society that is being primarily affected by a decision, is excluded from the decision-making, and does not even possess the right to debate the decision for "formidable reasons", as shockingly stated by the Apex Court on 16.09.2019, it transports one back to the times of the colonial era wherein rules and regulations were imposed by the colonisers for our alleged greater good as we were rendered incapable of holding civilized debates. The citizens of Kashmir have similarly been relegated to the position of "The Other", not to be trusted with any access to the internet, a basic fundamental right under Article 19(1)(a).

The ambit of Article 19(2), which stipulates the reasonable restrictions imposed by the State, in accordance with law, upon Article 19(1)(a), for the furtherance of "security of the State" and "public order", has been clearly exceeded by the State in the instant case. It is pertinent to note here that restrictions can only be imposed by a duly enacted law, and not by an Executive action (

Express Newspapers (P) Ltd. v. Union of India in 1986).

By placing an entire state under a siege as a mock-Emergency, there is prima facie over-breadth of the Executive's actions. It is baffling that the Court has not yet attempted to examine the merits of the Government's claims for the need for complete blockade of communication channels and internet, which prima facie looks excessive and disproportionate. On the basis of unfounded apprehensions, a State-wide lockdown cannot be initiated as it goes against the basic tenets of a participatory democracy. Hence, the Court should examine if the Centre's measures are justifiable on constitutional grounds. Instead, it is indulging in escapism in the form of "jurisprudence of adjournments".

The Kerala High Court judgement can therefore, be a dim guiding light for the Supreme Court and aid it to pave its way back to its days of K.S. Puttuswamy and, to its primary duty of being the guardian of the people. Restoration of the Right to Access Internet; the salient of all rights in this technology-driven democracy, is urgently needed so as to dispel the notion of an Emergency-like situation, and to prevent the State from widening the ambit of "reasonable restrictions", as failing to do so could be a harbinger of disastrous consequences for our Fundamental Rights.