'You Have The Right To Remain Silent'- Story Behind Miranda Rights

Swapnil Tripathi

2 Jan 2021 2:51 PM IST

Anyone interested in Hollywood crime thrillers or drama, has at least once come across a scene where an arrest is being made by the police. The officer while carrying out the arrest mandatorily utters the following words,

"You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you. Do you understand the rights I have just read to you? With these rights in mind, do you wish to speak to me?"

I am sure this rings a bell. While these rights are known by every American and even Indian, since they are in place in India as well (in some form), their origin story is not much discussed. These rights arose from the famous case of Miranda v. Arizona and were hence, called the Miranda Rights. The twists and turns of the case, make it suitable for an independent movie or show of itself. In the present post, I shall take you through this important case.

Central to this case are two key amendments of the Constitution i.e., Fifth Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment. They are briefly explained. The Fifth Amendment guarantees the right against self-incrimination by stating that no person shall be compelled in a criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law. Whereas, the Fourteenth Amendment contains the due process clause guaranteeing to every person that she/he shall not be deprived of her/his life, liberty or property without due process.

Background Facts:

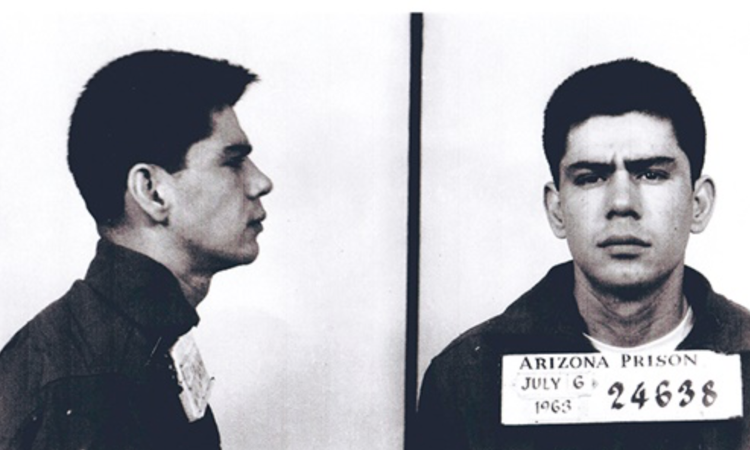

On 3 March 1963, in Phoenix, Arizona an 18-year-old woman named Lois Ann Jameson (name changed) was walking home by herself. Suddenly, a car pulled up near her and the driver Ernesto Miranda, forcefully dragged her in the car. She was tied up using ropes and Miranda told her that he wouldn't hurt her if she remained quiet. Ann did not scream for help. He raped her and later dropped her to the spot she was picked from. Ann reached home and informed her sister, who called the police.

Ann described the rapist as a Mexican man, about 27 or 28 years old, about 5 feet 11 inches tall, about 175 pounds in weight, with short, black, curly hair and dark-rimmed glasses. The detectives identified three-four Hispanic men matching the description, which included Miranda as well. Ann was called to the station to identify the rapist. She did not positively identify Miranda and merely said that he looked similar. The detectives however told Miranda that he had failed the line-up and was identified by the victim. Thereafter, Ann was brought to the room and Miranda was asked, 'whether that was the girl?' to which he responded in the affirmative. Detectives asked Miranda if he would sign a confession, to which he agreed.

Years later, Miranda described his experience in the interrogation room as follows, "Once they get you in a little room and they start badgering you one way or the other, 'you better tell us, or we're going to throw the book at you' . . . that is what was told to me. They would throw the book at me. They would try to give me all the time they could. They thought there was even the possibility that there was something wrong with me. They would try to help me, get me medical care if I needed it. . . . And I haven't had any sleep since the day before. I'm tired. I just got off work, and they have me and they are interrogating me. They mention first one crime, then another one, they are certain I am the person . . . knowing what a penitentiary is like, a person has to be frightened, scared. And not knowing if he'll be able to get back and go home."

Nobody knew that these two hours of police interrogation would spark a legal battle that would result in one of the most important judgments on the rights of the accused.

In trial, his lawyer Alvin Moore argued that during the interrogation, Miranda did not know that he had any rights, much less the right not to witness against himself. His lawyer point blank asked the detectives, whether it was their practice to advise the arrested individuals that they are entitled to the services of an attorney before making any statements. The detectives answered in the negative. The jury's verdict was against Miranda and he was found guilty for the offences of kidnapping and rape.

An appeal was filed first before the Arizona Supreme Court and later before the United States Supreme Court. Miranda's lawyer had two key arguments i.e., (a) Miranda was coerced into confession and (b) an accused has a right to see an attorney before her/his trial. Emphasis was laid on the second argument. The lawyer justified his strategy in the following words, 'The rich and the educated know that they're entitled to counsel, that they don't have to testify against themselves. The poor and the ignorant and the foreign born don't know these things. I think that a legal system that is calibrated to take advantage of the ignorance of the ignorant is dreadful…'

Case reaches the Supreme Court:

This case arose during the time of Chief Justice Earl Warren, known to be extremely progressive and liberal. The Court reached its verdict by a vote of 5:4, ultimately holding that prosecution cannot use statements that stem from the interrogation of the accused unless it has complied with certain procedural safeguards. The procedural safeguards were as follows,

'Prior to any questioning, the person must be advised that he has a right to remain silent, that any statement he does make may be used as evidence against him, and that he has a right to the presence of an attorney, either retained or appointed. The defendant may waive these rights, provided the waiver is made voluntarily, knowingly, and intelligently.'

Justice Harlan wrote a strong dissenting opinion wherein he argued that protection against self-incrimination does not forbid all pressure to extract a confession from the accused.

It is argued by many that the Court's decision was swayed by the individual Justice's political philosophies and they voted on class lines. For instance, judges born to families in humbler circumstances looked at the interrogation room through the eyes of the defendant, those born to privileged families looked at it from the eyes of the police officer.

The Earl Warren Supreme Court that decided Miranda V. Arizona | Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Aftermath: Is Miranda Freed?

Miranda was confident that the Court's decision would be in his favour and he would be freed. In fact, his father had even bought a bottle of Scotch for his son, to celebrate his homecoming. However, the Court did not free Miranda and instead, ordered a fresh trial. In other words, the Court held that primary evidence against Miranda i.e., the signed confession was inadmissible.

A second trial was scheduled and Miranda's past came to haunt him. Miranda was in an unmarried relationship with one Twila Hoffman (known as common law wife). While Miranda was in prison, Hoffman met another man and had a child with him. When Miranda heard this news, he wrote to the authorities stating that Hoffman was an unfit mother and hence, he desired the custody of the child, once he was released.

Days before the trial, Hoffman approached the investigating officer and told him that on 16 March 1963, shortly after Miranda's arrest she had visited him in the jail and he had confessed his crime to her. Hoffman agreed to testify in Court as well. It was argued by Miranda's lawyer that Hoffman's story was made up, just to retain the custody of her child. However, the Judge was convinced with the testimony and allowed it. Subsequently, the jury found Miranda guilty of the crimes of kidnapping and rape. He was sentenced for 20 to 30 years. The appeals up to the Supreme Court failed.

Fate catches up:

Interestingly, Miranda was released from the prison early on good behaviour. He would often be found at the steps of the very Court that tried him, selling autographed 'Miranda Rights' cards for two dollars each. Despite trying to stay clean for a few months, Miranda started drinking and playing cards. In a bar called La Amapola, he got into a fight and was stabbed twice. Destiny caught up with him and he was taken to the very hospital (Good Samaritan Hospital) where Ann was taken after her rape. He passed away. When the police arrested the killer's accomplice, they took out a card and read, 'You have the right to remain silent…'