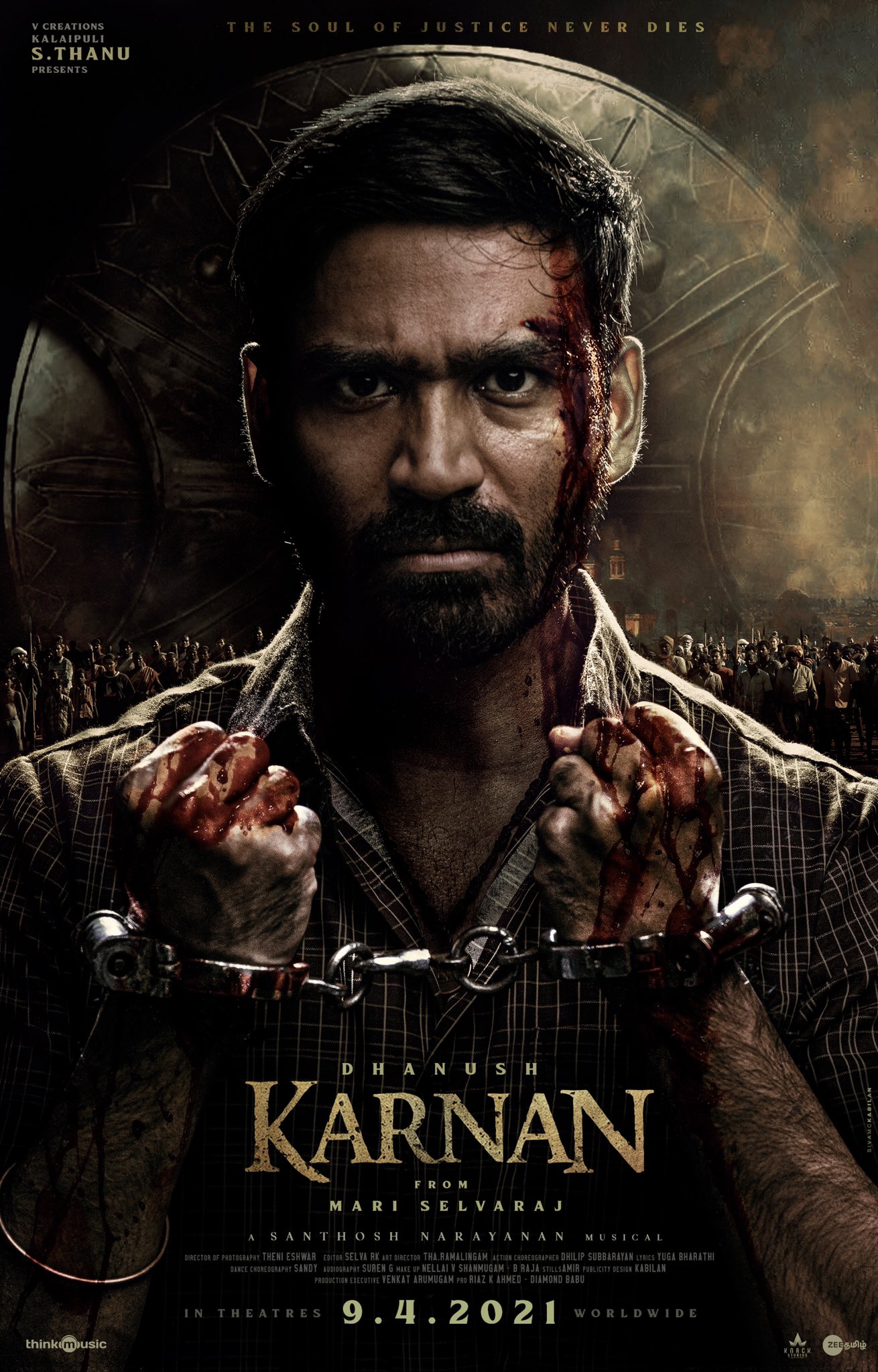

Law On Reels: 'Karnan': A Melancholic Ode Of Oppression

Shaileshwar Yadav

30 May 2021 12:11 PM IST

The movie Karnan (2021), released on 9th April 2021, a week after Mandela (2021), unleashes the political quotient and intricacies of caste oppression in rural India. My review of Mandela (here) focused upon the act of manual scavenging through the cinematic angel. In comparison, Mandela dealt with the significance of caste in the election sphere, whereas Karnan questions the restrictions on mobility in society.

Karnan, directed by Mari Selvaraj starring Danush and Yogi Babu, is set in the 1990s in a small village of Tamil Nadu, Podiyankulam (lower-caste village). The storyline runs along with the efforts of Podiyankulam people for a bus stand led by Karnan. Karnan is a young villager and protagonist played by Dhanush. Though Podiyankulam had no access to a bus stop, its adjacent village Melur (village of upper-caste), had its bus stand, which is seen as a sign of mobility and wider public acceptance.

The quest for mobility takes a turn when the people of Podiyankulam find themselves in a clash with the people of Melur and the State. This clash takes a violent turn when many villagers of Podiyankulam are picked up from their houses and are violated of their rights and human dignity. The State here acted as an agent of caste oppression and led into a conflict with the villagers. The dominant factor of violence in India boils down to caste; it transcends from either the State or non-state actors comprising of upper-caste.

Violence by State

The jurisprudence of criminal justice administration has dealt with the quotient of custodial violence and deaths extensively. However, not much heed has been paid to the systematic oppression of lower-caste and violation of their rights in police custody. According to a report, out of 125 custodial deaths registered in 2019, 13 victims belonged to lower-caste. It is noteworthy that these victims were picked up for petty crimes such as theft, cheating, and gambling. Moreover, statistics on 'custodial torture not resulting in deaths' are unlikely to be recorded. While the District magistrates and Superintendents of the police must report any custodial death within 24 hours of its occurrence to the National Human Rights Commission, the case for custodial torture not resulting in deaths goes without any such reporting.

However, the cases of custodial violence have been reported by news agencies time and again. In one such case, five tribals were picked up by police in the Alirajpur district of Madhya Pradesh on the allegations of assaulting a police officer. After being released on bail, they revealed the tragic tale of custodial violence. In yet another case, two lower-caste brothers were illegally detained by the police merely on the speculation of damaging a temple's statue for four days and were beaten up in Rajasthan.

In the film, upon hearing about the custodial violence, Karnan, along with others, vandalizes the police station. Mari Selvaraj uses this event in the film to display the portrait of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar hanging amidst all the chaos. The portrait's presence has a profound significance of how helpless the Constitution and laws remain if the people enforcing them are corrupt. Ambedkar had anticipated the fate of the Constitution, in his final speech in Constituent Assembly, he had warned –

"…however good a Constitution may be, it is sure to turn out bad because those who are called to work it, happen to be a bad lot. However, bad a Constitution may be, it may turn out to be good if those who are called to work it, happen to be a good lot…. The Constitution can provide only the organs of State such as the Legislature, the Executive and the Judiciary. The factors on which the working of those organs of the State depends are the people and the political parties they will set up as their instruments to carry out their wishes and their politics."

Violence by Non-State Actors

Ambedkar's work for social revolution through the Constitution falls short where the people fail to comply with the principles and spirit of it. Similarly, the debate around caste oppression is not limited to the State but also includes the non-state actors that have escalated it. The idea of caste and discrimination is deeply embedded in the Indian fault lines. The common factor to most of the hate crimes against the lower-caste community could be traced as the reluctance of the upper-caste to accept them as equals. In one such recent incident, a lower-caste man was beaten brutally merely for sporting moustaches in Gujarat. These crimes are often subjected as a form of 'punishment' for riding a horse, owning a horse, fetching water from the same sources, sitting on a chair, et al. In 2018, about 65 percent of the hate crimes were against lower-caste people by the upper-caste. Shockingly, these hate crimes occur even after enacting specialized legislation to protect lower-caste, commonly known as the 'Atrocities Act.' Ironically, as discussed above, the fallacy of implementing this legislation lies in the implementing authority, which itself is an oppressor. The same has been portrayed in the movie, wherein for using the bus stand of the Melur village, people of Podiyankulam village were beaten up, assaulted, and women molested, first by the villagers of Melur (non-state actors) and then the police (State).

Significance of the eagle and the tied donkey

Though the film is both saddening and disturbing, it also leaves messages through different metaphorical events. In the film's opening scene, an eagle takes away chicken from an old lady's house. Next, the lady could be seen pleading to the eagle to return her chicken, which irks Karnan, as he believes that one must not live on the mercy of others. A sense of human dignity seems the accurate description of Karnan's feeling. It also shows the stark contrast between the older generation and the younger ones, the former had accepted oppression as their destiny, but the younger generation ought to fight for their dignity and resist the conventional social hierarchy. Moreover, a donkey with tied forelimbs to restrict its movement could also be spotted in the movie. The tied forelimbs portray helplessness and shackles of caste, restricting social mobility.

Karnan, after Mandela, serves another blow to the caste ignorant film industry. It would be unfair to judge the film only on the storyline, as the director uses nature, mysticism, and folk art to convey oppression in a very subtle manner. The cinematography and equal importance to all the characters in the film makes it stand out. In a nutshell, with Karnan, the message is loud and clear; it is resistance against oppression.

Views are personal

The Author is a student at National Law University, Jabalpur.

(This is the twenty-third article in the "Law On Reels" series, which explores legal themes in movies)