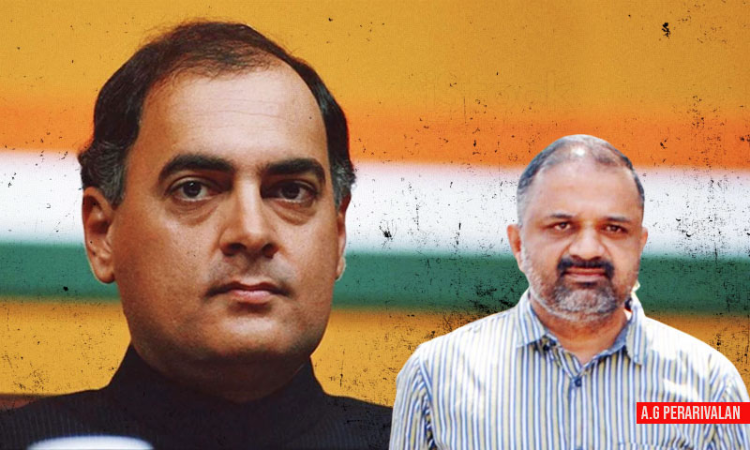

Why Not Release AG Perarivalan In Rajiv Gandhi Assasination Case? Supreme Court Asks Centre

Sohini Chowdhury

27 April 2022 7:05 PM IST

Next Story

27 April 2022 7:05 PM IST

In a significant development, the Supreme Court on Wednesday asked the Central Government why can't AG Perarivalan, the convict in the Rajiv Gandhi assasination case, be released, having regard to the fact that the Court has been releasing many prisoners who have served over 25 years of sentence.The Court said that without deciding the legal issue as to who is competent to grant him remission...