Capital Conundrum: Threading The Needle Between Governance And History

Saurabh Gupta

10 Dec 2025 10:53 AM IST

Next Story

10 Dec 2025 10:53 AM IST

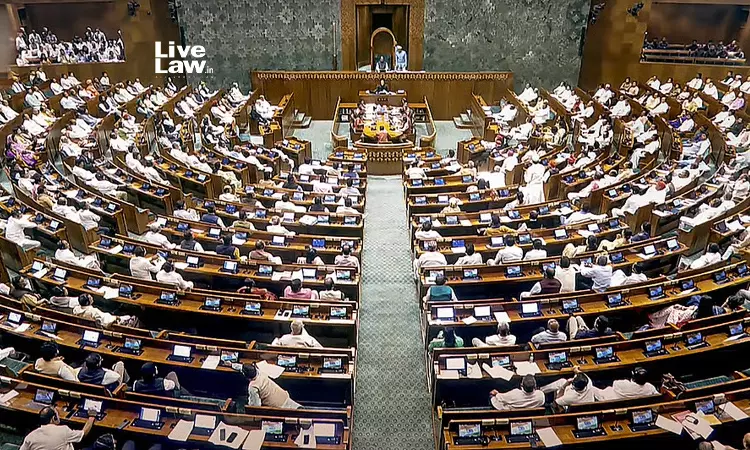

In the arcane world of Indian parliamentary procedure, it is rare for a mere listing in a legislative bulletin to trigger uproar in a state. Yet, that is precisely what happened recently. The inclusion of the Constitution (131st Amendment) Bill, 2025 in the tentative list for the Winter Session, aimed at bringing the Union Territory of Chandigarh under Article 240, set off a political...