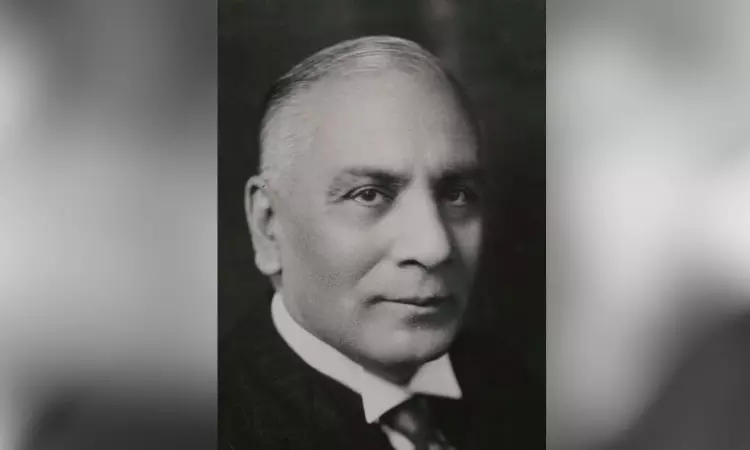

Tej Bahadur Sapru- A Sesquicentennial Tribute

V. Sudhish Pai, Senior Advocate

8 Dec 2025 10:36 AM IST

December 8, this year is the 150th birth anniversary of Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru who was one of the best legal minds of the country. It is only appropriate that we remember him and light his memory. The likes of him belong to the ages. Very rarely do we see someone like him.

A jurist and scholar of the highest repute, he was a great constitutional lawyer who achieved brilliant success. It is said that Sir Tej 'had something which does not necessarily go with superior intellect and character; he had charm, bordering on charisma, that inexplicable quality whose origins are veiled among the mysteries of life.' It is difficult to talk about law and its development in the country, especially constitutional developments in the first half of the 20th century, without making a special mention of Sir Tej. His career aptly illustrates the significance of the legal profession in the political and constitutional developments of India. He belonged to an era when the giants of the profession devoted time and thought not only on their goal but also on the method of realizing it.

Descended from an aristocratic Kashmiri Pandit family settled in the plains and quite a few of whose members were Dewans, Tej Bahadur Sapru was born at Aligarh on December 8, 1875. He was the only son of Ambika Prasad Sapru and his wife Gaura Sapru (née Hukku). His grandfather Radhakishen Sapru was in Government service and was a great friend of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, the founder of Aligarh Muslim University. Tej Bahadur grew up in a background of Muslim culture and language. From the beginning he displayed signs of uncommon intellectual ability and had a brilliant academic career. He secured his B.A. topping the list with first class Honours in English from Agra College, Agra in 1894 and M.A. in the first division in English Literature in 1895. The same year he graduated in law also. Principal Thompson and Professor Andrews of the Agra College had an abiding influence on him and they moulded his vision and character. He joined the Allahabad High Court Baras a pleader in 1898. In 1901 he took his Honours-in-Law as the Master's degree was then called. There was no branch of the law which he did not study and he did remarkably well in the examination. He earned the Degree of Doctor of Laws in 1902. He was the second person to earn a Doctorate of Laws of the Allahabad University, the first being his friend, Dr. Satish Chandra Banerji a year earlier in 1901. In 1906 he was enrolled as an Advocate of the High Court.

His period of waiting and brieflessness was short. He had his opportunity and made his mark quite early. Within a few years of his joining the Bar he got the opportunity of opposing Sir Rash Behari Ghose- one of the topmost lawyers in the country. It was a case in Hindu Law which Sapru argued brilliantly and he found his feet in the profession. He won compliments from the Bench. He successfully opposed Sir Rash Behari in a couple of cases. By 1910 he had come to be regarded as one of the leaders of the Bar. His reputation was established and he was a marked man in the United Provinces and even outside. From all parts of the country people from all walks of life including Princes and Governments sought his advice and his services.

Brilliant and profoundly learned in law and classics, his arguments were marked by a complete mastery over every intricate aspect of law and jurisprudence. His command over the language was perfect and accuracy of statement characterized his addresses in court. The flow of his erudition and the orderly array of his submissions were compared with 'incessant waves of an ocean.' His forensic style was sober and terse; his advocacy was sincere, upright and able. He had an imposing presence and a magnificent voice which arrested attention. His memory was colossal and his knowledge wide and deep: His son Justice P.N. Sapru says that if one were to wake Sir Tej up at two in the night and pose before him a difficult proposition of law, one could be sure that he would be able, without looking into any books, to trace the history of the legal doctrines involved. He believed that it was essential to know the legal history of the principles and doctrines. In the course of his meteoric professional career of half a century, during which time he occupied a unique position, he was thrice offered judgeship which he declined.

He was one of the foremost lawyers of his time. He was, however, something much more than a practising lawyer. He was essentially a jurist and an original thinker. It is believed that if only he had applied himself solely to the academic side of law, he might have been a Holdsworth, a Maitland or a Dicey. He was invited to deliver the Tagore Law Lectures and had prepared his lecture on The Liberty of the Subject which, however, remained undelivered. He had also written an exhaustive commentary on the Government of India Act, 1935 which was not published. His juniors included such outstanding persons as Purushotham Das Tandon, Sir Shah Sulaiman and Dr. Kailash Nath Katju.

His standards of professional conduct were of the highest order. A lawyer's function is to assist the courts in arriving at the truth. He would place all the facts and law correctly before the court. He was strongly opposed to lawyers helping clients to build up stories to win their cases. Sapru was of the firm view that the right of cross examination should not be misused by counsel: It is unethical to subject a witness to unnecessary harassment, cross examination is not meant to defame or harass people, questions reflecting upon a person's character or honour should not be put unless there was material justifying that being done. Counsel should not be guided by the client's prejudices or desire to wreak vengeance.

There were very few lawyers of greater rectitude than Sir Tej. He never talked about himself or advertised even remotely. He earned well. But he was never after money, it did not seem to have any value for him. He was not a money-making machine but a creative jurist dedicated to his high calling. Fees were charged by the hour, but they were never heavy. There was no bargaining, no nexus between the fee charged and the client's purse. It was all fixed, clean and above-board. He was very generous in his treatment of his juniors who were handsomely paid.

Sir Tej by his fearless and powerful advocacy became the indomitable champion of the forces of independence and defiance of arbitrary authority. He valiantly defended a veteran criminal lawyer Shri Kapil Deo Malaviya when he was issued with notice of contempt of court because of an article wherein he had commented about comparatively undeserving lawyers being raised to the Bench (1935 All LJR 125).

In 1926 two judges of the Allahabad High Court from the Indian Civil Service used to read all the cases at home and insisted on limiting the arguments of the counsel in court only to the points mentioned by them. The Bar was agitated; Sapru took a serious view of the matter and considered that the confidence of the public in the administration of justice would be shaken. At his initiative a resolution was passed by the Bar conveying to the judges the need for a more satisfactory procedure for hearing of cases. The then Acting Chief Justice Sir Cecil Walsh, having failed to exact an apology from the Bar, initiated contempt proceedings against the Bar including Sir Tej. Sir Benjamin Lindsay, the Senior Puisne recused himself stating that he refused to make himself ridiculous by such proceedings; the other English judges took a similar attitude. Then at the mediation of Sir Shah Sulaiman who was nominated to be on the Bench the matter was sorted out amicably.

In another case the Bench (Justice Boys and Justice Pullman) hearing an Execution First Appeal came to the conclusion that it was a reprehensible proceeding which amounted to an abuse of the process of the court and issued notice to the lawyer to argue whether in the circumstances the court had the power to order a legal practitioner to pay the costs personally. At Sapru's instance the Chief Justice Sir Grimwood Mears constituted a Full Bench of seven Judges which took a view different from the Division Bench (Santhanand Gir v. Basudevanand Gir, AIR 1930 All 225: 1930 All LJ 402: ILR 52 All 619 (FB)). In the course of the hearing Justice Boys said that the case had not been argued before him in the manner in which it had been placed before the Full Bench by Sir Tej nor were the authorities cited before him. Sir Tej thundered back that it could not, therefore, be said that whenever a judge thought that counsel was in the wrong he was necessarily in the wrong.

It would also be appropriate to recount Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru's bold advocacy in the Searchlight case (Emperor v. Murli Manohar Prasad, AIR 1929 Pat 72: ILR 8 Pat 323: 30 Cr LJ 741 (FB)) and Amrita Bazar Patrika (in re:), (AIR 1935 Cal 429). In the Searchlight contempt case when Sir Tej was arguing an intricate point, the Chief Justice of the Patna High Court said, “I have never known the law to be that, Mr. Sapru” to which in a fit of righteous indignation Sir Tej replied: “There is no such presumption in law that the judge knows the law.” In the sensational case in which Shri Tushar Kanti Ghosh, the editor of the Amrita Bazar Patrika was hauled up for contempt, when Sapru took the judges into subtle reasoning and case law, one of the judges remarked: “We cannot follow your reasoning” and Sir Tej boldly retorted: “It requires a judge to understand it.” Occasionally his arguments were far too subtle and learned for the judges he had to address. It was his principle not to take any fees from newspapers that were in trouble. It was the same with educational institutions and persons charged with political offences, all of which he did pro bono.

Although pre-eminently a civil lawyer, his versatile talents were also exhibited in a number of leading criminal cases in which he appeared. His argument on the question of corpus delicti and the evidence as to the disposal of the dead body in B.B. Singh's case, in which an ICS Officer was charged with the murder of a maid servant, was repelled by the courts in India, but ultimately prevailed in the Privy Council (Brij Bhusan Singh v. Emperor, AIR 1946 PC 38: 47 Cr LJ 336: 50 Cal WN 348).

There was hardly any branch of law, including Public International Law and Private International Law-Conflict of Laws, in which he could not claim to speak with knowledge and authority. It was, however, in the field of Constitutional Law that he reigned supreme, he was a master. The recognition of his great scholarship in that domain resulted in his appointment as the Law Member of the Government of India. In the making and shaping of constitutional thought leading to our Independence the name of Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru will occur to every constitutional historian. He was a member of the United Provinces Legislative Council during 1913-16. He did remarkable work in the Imperial Legislative Council during the First World War (1916-20). He was knighted in 1922. He was the Law Member of the Viceroy's Executive Council during 1920-23. The Viceroy, Lord Reading paid a most handsome tribute to Sir Tej as a lawyer at the farewell banquet he gave on Sapru's retirement as Law Member. Thereafter Sapru did very valuable work on the Reforms Committee. He represented India on several occasions and participated in the deliberations of the Round Table Conferences and the Joint Parliamentary Committee. He was also closely associated with, and instrumental in, the enactment of the Government of India Act, 1935 which formed the nucleus and cornerstone of our Constitution. The acme of his career was when he was made a Privy Councillor in 1934. In recognition of his outstanding merit and reputation as a jurist, the Oxford University conferred on him the Degree of the Doctor of Civil Laws.

Few enjoyed the large opinion practice that Sapru had developed. Perhaps there was hardly any lawyer in India who had such a large opinion work. It was a settled principle with him that opinions must be completely honest and if there was a possibility of a settlement on reasonable terms, the lawyer must advise the client to come to terms with his adversary. Sir C.P. Ramaswami Aiyer in a tribute to Dr. Sapru remarked, “Not every advocate of eminence is a good consultant. Sir Tej is a remarkable exception to this rule. From the humblest folk to most of the rulers of the Indian States, men and women all over India have learnt to rely on his legal opinions with the assurance that they will be thoroughly and safely advised.” It is of interest and significance that Tej Bahadur Sapru's selected legal opinions have been published as a book under the title Responsa.

In his political leanings he was a strict constitutionalist and a liberal. As Justice Khanna said: (Address to the Allahabad Bar Association to commemorate Sapru's birth centenary) Sir Tej's contribution in the field of constitutional law and public life was that he avoided extremes. He was a moderate and 'moderates have an important role to play in every society… they do commendable work in eliminating friction, providing smoothness to public life and finding a way out of the impasse.' For several decades he symbolized the golden mean in Indian politics. He was a successful mediator between warring groups and brought about the Gandhi-Irwin Pact. However, he was a nationalist to the core as is so clear from his response to General Smuts who refused to allow any citizenship to Indians domiciled in South Africa: “We claim along with you equal citizenship in the same Empire. We are not willing to be relegated from King George's dining hall to King George's stables.” His public speeches were also characterized by the same rational attitude as his advocacy and there was no rhetoric.

In November 1944, the Sapru Committee was appointed by the Standing Committee of the Non-Party Conference to examine the whole communal question in a judicial framework. The Committee's Report contained a detailed historical analysis of the proposals and of each community and a rationale for its constitutional recommendations. He made a final but fruitless effort to avert partition. In 1945 Sir Tej was one of the lead counsel to defend the INA heroes.

Sir Tej seldom indulged in humour, but whenever he did, it was with devastating effect. It is said that a journalist in London rang him up one night to say: “Our Indian office has just cabled that you have been offered a peerage.” “What of it?” asked Sir Tej. “Well Sir, could I know what title you have chosen?” persisted the journalist. “Certainly”, replied Sir Tej, that inveterate smoker, “It is the Duke of Blazes” and put down the phone.

As a lawyer and as a man Sir Tej was gifted. If one were to ask as to what was particular about him, the reply would be what was not. Besides being an erudite scholar and an astute statesman, Dr. Sapru was a great gentleman. He was a person of wide culture and catholicity of outlook. Apart from law he was widely read in literature and humanities. His library- well stocked with books in different subjects- revealed a storehouse of vast erudition and he knew what was in those books. A voracious and fast reader, he could grasp the central idea in no time. He subscribed to a large number of journals and magazines, all of which he read. On his standing instructions, the booksellers used to send him all important books. His law library in particular was one of the best in India. It was sold by his heirs to the Supreme Court in 1950.

His conversation was full of anecdotes and a touch of humourous exaggeration but utterly devoid of malice. He was a great scholar of Persian and Urdu. There is an amusing incident which took place in Hyderabad when Sapru went to argue a case in which he was opposed by Jinnah. There was an original document in Persian and the counsel for the parties were requested to read it out for the benefit of the court. While Jinnah could hardly read Persian, Sapru fluently read out the entire document. This created a sensation and the following day's newspapers commented in flaming headlines on 'Pandit Jinnah and Maulvi Sapru'. Tej Bahadur's proficiency in Urdu was such that Maulana Abul Kalam Azad chose him as the only person competent to contribute in chaste, felicitous and faultless Urdu a Foreword to the collection of Essays written by the Maulana.

His life style was such that it was not possible even with his enormous income to save money or to invest it. Perhaps, he did not believe in investing money at all, says his son. He was a wonderful host who would throw lavish parties and entertain guests. It must also be noted that he was of a very charitable disposition. He espoused the cause of education and supported young students in the universities liberally. He even helped students go abroad for higher studies. He never talked about or advertized his charity; not even his family knew what he was giving or to whom.

Sapru's famous house at 19, Albert Road was the intellectual and social hub of Allahabad and a destination for all Indian and foreign celebrities, the other meeting place being 'Anand Bhavan' of the Nehrus. Sir Tej used to hold there what came to be known as his 'Darbar.' V.S. Srinivasa Sastri has described such darbars picturesquely and written: His evenings he enjoys most, lounging in loose night apparel, imbibing tobacco in every form except as snuff, and surrounded by cronies who lay it on, as Disraeli did to Victoria, with a trowel. People from all walks of life gathered there as equals and took part in the exchange of news and views and recitations and repartees. All that was an education in itself. He possessed a robust constitution and phenomenal digestion in spite of his love for rich and delicious food and sedentary lifestyle which was a puzzle to the doctors. He was an excellent host and entertained sumptuously. He always dressed immaculately.

Everything about Sapru was grand and magnanimous and anything that savoured of pettiness or triviality was scoffed at. His personality was so dominating, it is said, that when he entered the scene no one else seemed to exist. A thinker and a scholar with a sensitive and scintillating mind he moved through life wearing distinction with unassumed ease. He was second to none in upholding the highest traditions of professional standards. In personal and public life also, he upheld the best traditions of social conduct and behaviour. All this invested him with a moral grandeur which, coupled with professional equipment and vast erudition, made him loved and respected at home and abroad.

His one-time pupil and great contemporary Dr. K.N. Katju, speaking of the leaders of the Bar, remarked, “The Allahabad Bar does not still realize the immensity of its obligations to the personality of Dr. Sapru. Not only numerous beginners have sat at his feet, but his chamber has been the nursery of judges. He is the soul of honour, and his uprightness of conduct and his professional rectitude have been a beacon light to lawyers throughout the United Provinces all these years.”

The tribute paid to him by the Rt. Hon'ble Srinivasa Sastri who spoke of Sapru as one with 'unsurpassed knowledge and experience of affairs' is equally worth recalling, “Nature fashioned Sapru in one of her lavish moods. She put into his blood several elements of greatness-generous susceptibilities, scorn of meanness, large ideas, command of men.”

Sapru passed away on January 20, 1949 having lived a full and active life. A magnetic personality of great nobility and integrity, he was “learned and lovable, the acme of honour and the pink of courtesy”.

To generations who have passed their lives in the law, his is truly clarum et venerabile nomen- a celebrated and venerable name. The love and respect with which we light his memory is a measure of his eminence as a man and a lawyer and of his remarkable contribution in various fields.

Author is Senior Advocate, Supreme Court of India. Views Are Personal.