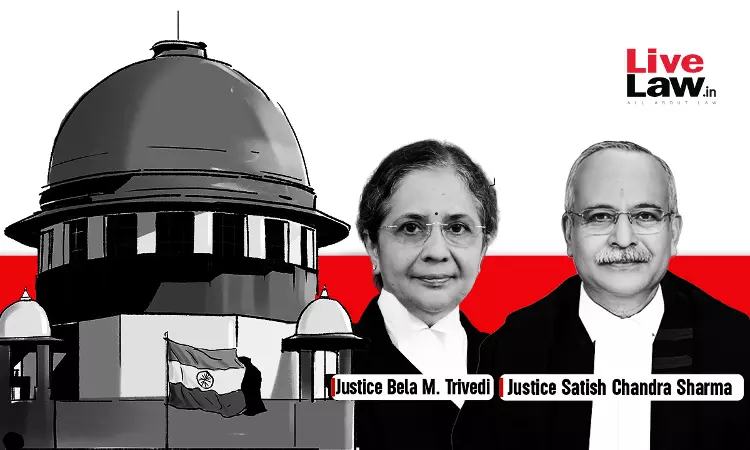

Principles To Be Followed By Appellate Courts In Deciding Appeals From Acquittal : Supreme Court Explains

Yash Mittal

14 Feb 2024 8:17 PM IST

Next Story

14 Feb 2024 8:17 PM IST

Recently, the Supreme Court observed that if the appreciation of evidence leads to two possible views, then the decision of the Trial Court acquitting the accused could not be reversed by the Appellate Court merely because there exists another view that led to the conviction of the accused.According to the court, if the appreciation of evidence leads to two possible views, then the view...